The debate on the merits of conserving the country's iron ore resources through a combination of punitive export tax and railway freight on the mineral destined for exports has remained inconclusive. In the past couple of years, however, India, no longer an exporter of substantial iron ore, has missed out more than once to capitalise on global bursts in prices of the mineral.

At $137 a tonne, iron ore prices have climbed to a two-month high on accelerated buying by China. The world's second-largest economy raised steel production 8.3 per cent to 652.48 million tonnes (mt) in the first 10 months of this year. No wonder China, which alone had a share of 49.39 per cent in the global steel output of 1.321 billion tonnes till October, imported the most ore in September - 74.58 mt. In October, Chinese imports fell to 67.83 mt. However, on a year-on-year basis, these were 20 per cent more. The rally in ore prices has continued. Besides steel production and iron ore imports, the rally is drawing sustenance from Chinese growth rising to 7.8 per cent in the third quarter from 7.5 per cent in the previous quarter, helped, to an extent, by government stimulus focused primarily on urban infrastructure building.

The bullishness in iron ore since July has led commodity forecasters with leading merchant bankers and research houses to reconsider the likely future prices of the mineral used in making steel. The somewhat surprising spurt in Chinese demand and a Morgan Stanley report saying the iron ore seaborne market is to experience a supply shortfall of 25 mt in the first half of 2014, before a surplus of 49 mt in the second half, explains why experts had to redo pricing estimates. Morgan Stanley has now settled for a 2014 first-half iron ore price of $130 a tonne, against its earlier estimate of $125 a tonne. Even for the second half, when the seaborne market will start contending with surplus resulting from mines expansion in Brazil and Australia in particular, the expected price is $3 higher at $120 a tonne.

According to World Steel Dynamics, by the end of 2014, mining groups across the world will bring into production an additional 483 mt of iron ore, in which the share of South America will be 208.8 mt. A Bloomberg report lists some major expansion programmes of the world's leading miners for which iron ore accounts for the most revenue and profits.

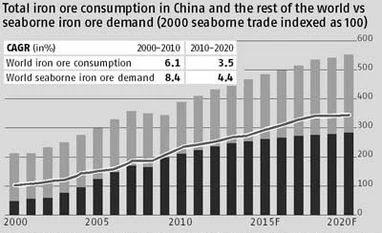

For Vale, the world's largest iron ore producer, the $3.5-billion Carajas expansion in Brazil will soon be ready to add 40-mt capacity. This is one of the several plans of the Brazilian miner to raise overall production capacity by half to 450 mt by 2018. Richly endowed with iron ore, Australia's Pilbara region is seeing much action, with Rio Tinto set to raise production in that area 60 mt to 360 mt, BHP completing the reopening of a mine ahead of schedule at Jimblebar, and Fortescue committed to tripling its capacity to 155 mt. All the expanding groups are risking investment in expectation of growing Chinese ore demand. Imports by China account for about two thirds of global iron ore trade. The country had raised imports 8.4 per cent to 743.6 mt in 2012. In the first ten months of this year, imports rose 10.1 per cent to 668.4 mt. Australia's Bureau for Resources & Energy Economics (BREE) has scaled up increased its estimate for Chinese iron ore imports for next year 8.3 per cent to 872 mt, compared to its forecast in June. Australia is the biggest suppliers of the mineral to China.

But why is the global iron ore industry outside China not betraying its discomfort over the likely steep price falls on new supplies? Nomura thinks iron ore prices will average $100 a tonne in 2015, while Australia's BREE expects 2018 average prices to stand at $91 a tonne. Industry leaders have been able to keep production costs at $50-55 a tonne and, therefore, in the future, they will be recording decent profits, not extraordinarily high ones. But any price collapse should see drying up of supply from Chinese mines, where production cost is about $100 a tonne.

At $137 a tonne, iron ore prices have climbed to a two-month high on accelerated buying by China. The world's second-largest economy raised steel production 8.3 per cent to 652.48 million tonnes (mt) in the first 10 months of this year. No wonder China, which alone had a share of 49.39 per cent in the global steel output of 1.321 billion tonnes till October, imported the most ore in September - 74.58 mt. In October, Chinese imports fell to 67.83 mt. However, on a year-on-year basis, these were 20 per cent more. The rally in ore prices has continued. Besides steel production and iron ore imports, the rally is drawing sustenance from Chinese growth rising to 7.8 per cent in the third quarter from 7.5 per cent in the previous quarter, helped, to an extent, by government stimulus focused primarily on urban infrastructure building.

The bullishness in iron ore since July has led commodity forecasters with leading merchant bankers and research houses to reconsider the likely future prices of the mineral used in making steel. The somewhat surprising spurt in Chinese demand and a Morgan Stanley report saying the iron ore seaborne market is to experience a supply shortfall of 25 mt in the first half of 2014, before a surplus of 49 mt in the second half, explains why experts had to redo pricing estimates. Morgan Stanley has now settled for a 2014 first-half iron ore price of $130 a tonne, against its earlier estimate of $125 a tonne. Even for the second half, when the seaborne market will start contending with surplus resulting from mines expansion in Brazil and Australia in particular, the expected price is $3 higher at $120 a tonne.

According to World Steel Dynamics, by the end of 2014, mining groups across the world will bring into production an additional 483 mt of iron ore, in which the share of South America will be 208.8 mt. A Bloomberg report lists some major expansion programmes of the world's leading miners for which iron ore accounts for the most revenue and profits.

For Vale, the world's largest iron ore producer, the $3.5-billion Carajas expansion in Brazil will soon be ready to add 40-mt capacity. This is one of the several plans of the Brazilian miner to raise overall production capacity by half to 450 mt by 2018. Richly endowed with iron ore, Australia's Pilbara region is seeing much action, with Rio Tinto set to raise production in that area 60 mt to 360 mt, BHP completing the reopening of a mine ahead of schedule at Jimblebar, and Fortescue committed to tripling its capacity to 155 mt. All the expanding groups are risking investment in expectation of growing Chinese ore demand. Imports by China account for about two thirds of global iron ore trade. The country had raised imports 8.4 per cent to 743.6 mt in 2012. In the first ten months of this year, imports rose 10.1 per cent to 668.4 mt. Australia's Bureau for Resources & Energy Economics (BREE) has scaled up increased its estimate for Chinese iron ore imports for next year 8.3 per cent to 872 mt, compared to its forecast in June. Australia is the biggest suppliers of the mineral to China.

But why is the global iron ore industry outside China not betraying its discomfort over the likely steep price falls on new supplies? Nomura thinks iron ore prices will average $100 a tonne in 2015, while Australia's BREE expects 2018 average prices to stand at $91 a tonne. Industry leaders have been able to keep production costs at $50-55 a tonne and, therefore, in the future, they will be recording decent profits, not extraordinarily high ones. But any price collapse should see drying up of supply from Chinese mines, where production cost is about $100 a tonne.

)