A subdued trend is likely to continue in industrial commodities until the third quarter of the current calendar year, due to weak global economic sentiment which has reduced their demand from consumer industries.

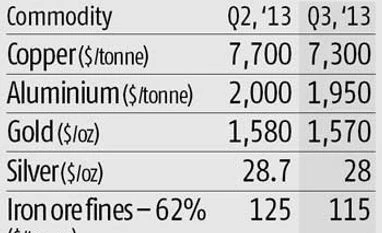

After a robust start at the beginning of this year, industrial commodities fell substantially due to lack of a clear direction from the US, the world’s largest economy. The average price of Brent crude oil, for example, is expected to fall from $113.19 a bbl in the first quarter of 2013 to $110 in the second and third quarters. Similarly, the average iron ore price is set to decline from $148 a tonne in Q1 to $125 a tonne in Q2 and further to $115 and $110 a tonne in Q3 and Q4, respectively.

The price of copper on the London Metal Exchange (LME) might decline from $7,927 a tonne in Q1 to $7,700 a tonne in Q2 and further to $7,300 a tonne and $7,000 in Q3 and Q4, respectively.

“From the point of view of developed countries, both stimulus and disinflation depends almost entirely on the behaviour of oil and energy prices. On the contrary, commodity exporters are likely to face a combination of deteriorating trade balances and potentially weaker currencies, and relatively high inflation because of rising food prices. Indeed, even if the jury is still out on the trajectory of oil prices, the outlook for base metals and other non-oil-related commodities is soft. However, food inflation, which is a larger component of the consumer price index baskets in poorer commodity exporters, is driven in part by frequent weather and supply shocks, and in part by increasing demand from wealthier consumers in China and other emerging markets,” said Igor Arsenin, an analyst with Barclays Capital.

With a rise and fall in the employment and household data, respectively, in the United States, the $85-billion monthly economic booster is likely to continue to support the country’s economy from a possible fallout. This indicates weak industrial activity, resulting in lower demand for global commodities.

The commodity outlook is likely to be important to forecasting the dynamics of interest rates and currencies in the second half of 2013. Low commodity prices would provide stimulus to consumers in industrialised counties. At the same time, these would contribute to the current disinflationary environment caused by low global demand, allowing central banks to continue to pursue stimulative monetary policy, adding another lever to growth.

Importantly, almost 50 per cent of the increase in oil demand in recent years has been generated by China and India. The net demand increase in the US is now close to zero and is likely to stay low in the future because of increases of energy efficiency. While global demand is likely to grow at approximately a one per cent annual rate, it can be comfortably met by increases in supply.

Historically, cost factors appear to have been highly dynamic, with the marginal cost of production (and consensus long-term forecasts) tending to move up with spot prices and then falling as the cycle turns down. Costs (like all market prices) are endogenous to the broader economic environment.

Perhaps the largest driver of costs remains the value of exchange rates in the big producing countries.

For iron ore, a concentrated industry structure could induce a different cost-price response as supply surpluses grow in the second of 2013 and 2014. This is especially so as Australia is supplying a growing share of seaborne iron ore – the depreciation of the local currency is likely to trim back production costs rapidly.

After a robust start at the beginning of this year, industrial commodities fell substantially due to lack of a clear direction from the US, the world’s largest economy. The average price of Brent crude oil, for example, is expected to fall from $113.19 a bbl in the first quarter of 2013 to $110 in the second and third quarters. Similarly, the average iron ore price is set to decline from $148 a tonne in Q1 to $125 a tonne in Q2 and further to $115 and $110 a tonne in Q3 and Q4, respectively.

The price of copper on the London Metal Exchange (LME) might decline from $7,927 a tonne in Q1 to $7,700 a tonne in Q2 and further to $7,300 a tonne and $7,000 in Q3 and Q4, respectively.

“From the point of view of developed countries, both stimulus and disinflation depends almost entirely on the behaviour of oil and energy prices. On the contrary, commodity exporters are likely to face a combination of deteriorating trade balances and potentially weaker currencies, and relatively high inflation because of rising food prices. Indeed, even if the jury is still out on the trajectory of oil prices, the outlook for base metals and other non-oil-related commodities is soft. However, food inflation, which is a larger component of the consumer price index baskets in poorer commodity exporters, is driven in part by frequent weather and supply shocks, and in part by increasing demand from wealthier consumers in China and other emerging markets,” said Igor Arsenin, an analyst with Barclays Capital.

With a rise and fall in the employment and household data, respectively, in the United States, the $85-billion monthly economic booster is likely to continue to support the country’s economy from a possible fallout. This indicates weak industrial activity, resulting in lower demand for global commodities.

The commodity outlook is likely to be important to forecasting the dynamics of interest rates and currencies in the second half of 2013. Low commodity prices would provide stimulus to consumers in industrialised counties. At the same time, these would contribute to the current disinflationary environment caused by low global demand, allowing central banks to continue to pursue stimulative monetary policy, adding another lever to growth.

Importantly, almost 50 per cent of the increase in oil demand in recent years has been generated by China and India. The net demand increase in the US is now close to zero and is likely to stay low in the future because of increases of energy efficiency. While global demand is likely to grow at approximately a one per cent annual rate, it can be comfortably met by increases in supply.

Historically, cost factors appear to have been highly dynamic, with the marginal cost of production (and consensus long-term forecasts) tending to move up with spot prices and then falling as the cycle turns down. Costs (like all market prices) are endogenous to the broader economic environment.

Perhaps the largest driver of costs remains the value of exchange rates in the big producing countries.

For iron ore, a concentrated industry structure could induce a different cost-price response as supply surpluses grow in the second of 2013 and 2014. This is especially so as Australia is supplying a growing share of seaborne iron ore – the depreciation of the local currency is likely to trim back production costs rapidly.

)