The Securities and Exchange Board of India is mulling another increase in minimum public shareholding (MPS) requirements from the current 25 per cent to 30 per cent, or even 35 per cent, said three people in the know.

The discussions at the market regulator’s end are, however, at a nascent stage, clarified one of them.

India has traditionally been a promoter-driven market and increasing the threshold will ensure wider ownership through institutional investors, more market depth and better corporate governance standards.

“A wider ownership will improve liquidity and reduce the scope for price manipulation, besides bettering corporate governance standards,” said Pranav Haldea, managing director, PRIME Database. “Thus far, most private sector firms have complied with the Sebi requirement for a 25 per cent public float and raising it to 30 per cent or even 35 per cent should not pose a major challenge to most.”

An email to Sebi did not receive a response.

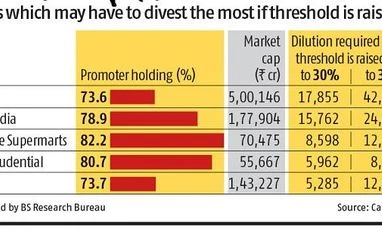

At present, 110 of the BSE 500 companies currently have less than a 30 per cent float. Twenty-five companies, including 13 public sector entities, have a public holding of less than the mandated 25 per cent. Raising the MPS in these 110 companies to 30 per cent will require promoters or companies to divest shares worth Rs 1.35 lakh crore at current prices, estimates show.

A few years ago, most listed companies in India had a promoter holding of nearly 90 per cent. Such high holding often led promoters to benefit at the expense of minority shareholders, said experts.

In 2014, the government had notified rules for a minimum 25 per cent public shareholding in listed public sector undertakings (PSUs). To comply with these norms, over 30 listed PSUs were required to raise their public shareholding to 25 per cent by August 21, 2017. They have now been given another one-year extension to meet the deadline.

Earlier in 2010, the non-PSUs were asked to attain a minimum 25 per cent public shareholding within three years, while the PSUs were told to raise their MPS to 10 per cent. Following the expiry of this deadline in June 2013, 105 listed companies were found to be non-compliant with these norms and necessary actions were initiated against them by the regulator.

A few weeks ago, too, Sebi had directed the stock exchanges to crack the whip on non-compliant companies, including imposing a fine of Rs 5,000 per day and freezing the promoters’ shares.

“Even today, in some companies, few institutional investors hold a sizeable chunk of the 25 per cent public float. Widening the float will, to some extent, help correct this anomaly and help in better price discovery,” said Sai Venkateshwaran, partner and head, Accounting Advisory Services at KPMG India.

High promoter holding remains the biggest hurdle in raising India’s weight among key global indices.

The MSCI Emerging Markets Index, for instance, uses the free-float market capitalisation for assigning weight among countries. An increase in weight could potentially bring in millions of dollars in foreign institutional inflows.

According to a Morgan Stanley report, India’s institutional ownership stood at 40.7 per cent at the end of June 2017, the highest level to date. Promoter holding, on the other hand, stood at 45.6 per cent, the lowest since March 2001.

India is somewhat peculiar when compared to other markets when it comes to high promoter holding, said experts. In developed markets such as the US, it’s generally the angel investors who invest first, followed by venture capital and private equity players. Listing on the bourses is the last stage after the company has matured and typically gone through several rounds of fund-raising. This means that by the time the company lists, the promoter shareholding is typically down to 20 per cent or less.

To be sure, India is now seeing the emergence of several new-age businesses, especially in sectors such as e-commerce, technology and health care, where the founders or promoters holding a minuscule stake in the company. As these companies tap the market, India’s free float is expected to rise.

FIXING THE FLOAT

- Wider ownership of public shareholding to improve liquidity and reduce the scope for price manipulation

- In 2010, non-PSUs were asked to attain minimum 25 per cent public shareholding within three years

- Later in 2014, govt had notified rules for 25 per cent MPS in listed PSUs

- They had to comply with these norms by August 2017 but were later given another year of extension

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)