Forty years ago, NASA's Viking mission made history when it became the first to successfully land a fully operational spacecraft on Mars.

As engineers and scientists planned for later missions to Mars, the rolls of microfilm containing the Viking data were stored away for safekeeping and potential later use.

It would be another 20 years before someone looked at some of these data again — in a digitised format.

"At one time, microfilm was the archive thing of the future. But people quickly turned to digitising data when the web came to be. Now, we are going through the microfilm and scanning every frame into our computer database so that anyone can access it online," said David Williams, planetary curation scientist at Goddard Space Flight Centre in Greenbelt, Maryland.

The spacecraft, dubbed Viking 1, touched down on the Martian surface on July 20, 1976. Its counterpart, Viking 2, followed suit and landed on September 3 in the same year.

The mission objectives were to obtain high-resolution images of the Martian surface, characterise the composition of the Martian surface and its atmosphere and search for life.

More From This Section

After years of imaging, measuring and experimenting, the Viking spacecraft ended communication with the team on Earth, leaving behind a multitude of data that scientists would study for the next several years.

The archive today houses much of NASA's planetary and lunar spacecraft data stored on microfilm and computer tapes, including the Viking data.

Williams works to digitise all of the data so that it can be easily accessed from the web.

He received a call from Joseph Miller, associate professor of cell and neurobiology at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, requesting data from the Viking biology experiments.

But all that was left of the data was stored on microfilm.

"I remember getting to hold the microfilm in my hand for the first time and thinking, 'we did this incredible experiment and this is it, this is all that's left,'" Williams said in a NASA statement.

"If something were to happen to it, we would lose it forever. I couldn't just give someone the microfilm to borrow because that's all there was," he added.

The archive team decided to tear open the boxes of microfilm and begin digitising the data.

Miller wanted to analyse the data from Viking's biology experiments to see if the Viking science team had missed something in the original analysis.

He concluded that one of the Viking biology experiments did, indeed, offer proof that life may exist on Mars.

In one of the experiments known as Labelled Release (LR), the Viking landers scooped up soil samples and applied a nutrient cocktail.

If microbes were present in the soil, they would likely metabolise the nutrient and release carbon dioxide or methane.

The experiment did indicate metabolism, but the other two Viking experiments did not find any organic molecules in the soil.

Unlike Viking, data from NASA rover Curiosity is uploaded to the Planetary Data System for easy accessibility.

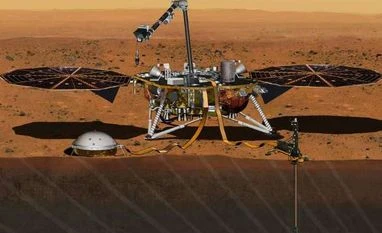

Today NASA has a fleet of orbiters and rovers on and around Mars, making key discoveries such as evidence of liquid water near the surface of Mars and paving the way for future human-crew missions.

The Mars 2020 rover recently passed an important mission milestone toward launch in 2020, arriving on Mars in 2021.

The mission is to seek signs of past life and demonstrate new technologies to help astronauts survive on Mars, with the goal of sending humans to the Red Planet in the 2030s.

)