The afternoon azaan of the Toot Serai mosque near my home serves as an alarm every day. As the imam starts calling the faithful to prayer, I am pulled out of my mid-morning torpor. This is how it has been for the past five years since I moved into Malviya Nagar. Not being too religious, I have never had any desire to find out where this mosque is — nor have I visited any of the gurdwaras or temples that dot the narrow roads of this congested, but very popular, south Delhi neighbourhood. Yet, I am acutely aware of the chequered demography of the area, and have enjoyed its many benefits over the years.

Soon after moving into a rented flat here in November 2013, my then flatmate took me on a tour of Hauz Rani, the narrow network of roads between Malviya Nagar and Khirki village. “Your life will be sorted,” he promised, and it was not an exaggeration. He took me straight to a shop where you could buy nahari, korma, paya, next to another one selling shami kebabs. In front of these stood carts selling tikka and one had a large tumbler full of Moradabadi biryani. A short walk down this road would reach another eatery selling chicken fried in an open wok overflowing with boiling oil.

On this trip, I also discovered a butcher who sold buffalo meat. That’s where I bought meat for Christmas a few weeks later when I first made Kerala-style buff curry. Culinary delights were innumerable, augmented by the rapid gentrification of the area. The metro station had led to a spurt in tenants — they came from all over the country, and the world. Many lived in incredibly small flats, with poor ventilation and little natural light. But, they brought along with them their cuisine and culture, as migrants and settlers often do. Yes, there were some landlords who told you not to cook meat or fish — but most could not care less as long as you paid the rent on time and did not keep the bills pending.

So, while there was a surfeit of dhabas on the Malviya Nagar market road, there was also one selling authentic Bengali or Chinese or Bihari or Rajasthani or Andhra cuisine. Indeed, venturing into Khirki, you could even chance upon a shop selling African spices and another preparing Afghan breads.

A German acquaintance recently accused me of romanticising — exoticising, othering — the Islamic past and present of Delhi. “This is your upper-caste, privilege guilt,” she chided me, adding that a recent spurt in communal violence across the country, evidenced by the rising number of hate crimes, had made me dewey-eyed. “Do you realise how problematic this is?” What I am clear-eyed about, however, is the syncretic culture that I had enjoyed for so long in my neighbourhood — which now hangs in a delicate balance.

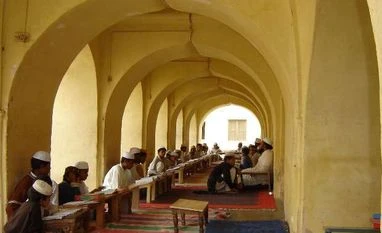

Last Friday, residents of the National Capital Region woke up to the news of an eight-year-old student of a madrasa in upscale south Delhi’s Begumpur area being killed in, what some newspapers described as, a playground scuffle. After initial reports of a “lynching”, it became evident that the killers themselves were 10-12-year-olds, residents of the nearby Balmiki camp. The authorities of the madrasa, attached to a Tughlaq-era mosque, claimed there had been skirmishes between the students and residents of the camp over a road adjacent to the institution. Following the death — the jury is still out on whether or not we can add it to the already rising incidence of hate crimes in recent years — the area was plunged into an uneasy calm.

It was the evening before Karva Chauth, usually a time of celebrations in the area. This year was no different. Barely a kilometre from the site of the crime, the temporary stalls of savouries and snacks, mehendi artists and gift sellers had come up. The market road was choked with traffic, as usual. The branded eateries — Domino’s Pizza, Pizza Hut etc. — were offering special dishes for the festival; so were the smaller shops. Returning home late at night, I still found many people in the market doing some last-minute shopping.

Of course, the festival itself is deeply patriarchal, requiring a wife to fast for the long life and health of her husband. Most of us don’t take part in it, but no one objects to others doing so. This tolerance of each other, this neighbourly bonhomie had characterised the area for so long. If the Hindu and Sikh pockets of Malviya Nagar indulged in frenetic Holi and Diwali, so did Khirki and Hauz Rani. Yes, the roads were always choked, because they are narrow and people park their vehicles on both sides, and sometimes people would lose their cool and shout at each other. But, no one had heard of a child being killed over it. Now, there is a rupture. We all have to live with this awful knowledge. Maybe the festivals will continue; the food shops will not shut down. Healing, however, would be long and complicated, if ever fully possible.

Every week, Eye Culture features writers with an entertaining critical take on art, music, dance, film and sport

)