Whether India’s exports are holding up is an important question. Goods and services sold abroad, like mobile handsets and IT services, have become an important driver of India’s growth. The recently released gross domestic product (GDP) print for June 2022 made that all too clear. The economy has grown just 4 per cent since June 2019, while exports have surged by a staggering 20 per cent over the same period.

The rise in exports also explains the improvement in India’s current account balance between FY19 and FY22. In fact, the improvement in India’s external accounts over those years helped raise buffers, i.e. India’s foreign exchange reserves, which the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) is now being able to use to keep the rupee stable in a period of high global volatility.

To understand what happens from here, we need to study export volumes, product by product. But we do not get an official disaggregated data series for the volume of goods and services exports. We only get “nominal” data, which isn’t that useful given a lot of the change is based on price movements and not export volumes.

So we created the “real” overall exports series ourselves, using nominal exports, relevant price indices and exchange rates. Our calculations are across sectors (such as textiles, software services, etc), and we aggregate up to get the overall “real” (goods and services individually) series.

We divide India’s export basket into four sub-components — high, medium and low technology goods exports, and services exports, respectively.

We find that real high-technology goods exports have grown the fastest over the last few years, alongside an impressive rise in real services exports, particularly IT exports. High-tech goods include electronics, engineering goods and pharmaceutical products.

Medium- and low-tech exports have been much weaker, currently just about at pre-pandemic levels.

Real medium-tech exports have remained weak for much of the pandemic period, but have seen a sharp rise in gems and jewellery in recent months. Over and above gems and jewellery, this category includes chemicals (excluding pharmaceutical products), refined petroleum, etc.

After rising in 2021, real low-tech exports have begun to inch lower since early 2022. This category includes food products, textiles, leather products, etc.

It can be argued that this divergence between strongly growing high-tech exports and weak low-tech exports has also exacerbated India’s K-shaped recovery where some have prospered and others stagnated. Firms and employees associated with high-tech exports have enjoyed better profits and salaries than those associated with medium- and low-tech exports.

The export story over the last few years is clear. What’s happened to it in the last few months?

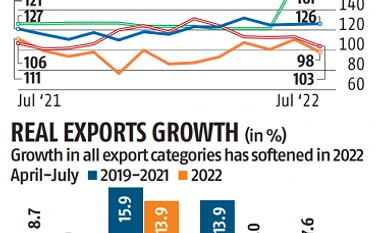

Recent data shows that overall real goods export growth is softening. After rising by an average 8.7 per cent year-on-year (in the April-July period of 2019-2021), it has fallen to 4.9 per cent (in the April-July period of 2022).

A closer look shows that while all categories have weakened, high-tech exports continue to grow the fastest, followed by medium-tech goods, and finally low-tech goods.

There’s both good and bad news from our analysis so far. The good news is that India was able to ramp up production in those goods and services which were most in demand during the pandemic period, namely IT services, mobile handsets, and pharmaceutical products. In fact, India has been gaining global market share in high-technology exports since 2017. Some of these new trade opportunities could outlast the pandemic.

The not-so-good news is that if the ongoing softening in export growth carries on for the rest of the year, the contribution of the exports sector to GDP growth will only be a quarter of what it was last year. In simpler terms, a drag on India’s GDP growth, arising from softening exports is imminent.

Also, while it is good to see high-tech exports doing relatively well, it is low-tech exports that create a significant number of jobs. India needs to work hard on sectors like textiles, leather and food exports.

And there are some policy implications too. A competitive rupee is one strategy to nurture exports growth during uncertain times. The dollar index has strengthened about 10 per cent since the start of the year, while the rupee has only weakened about 6 per cent during this time. The RBI has conducted substantial intervention in the foreign exchange market to keep the rupee relatively stable in the face of a balance of payments deficit.

Some gradual depreciation from here, we believe, could help nurture India’s exports and its economic growth.

The writer is chief India economist, HSBC Securities and Capital Markets (India)

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)