Whether or not the poverty line is too low is not an issue that can be fruitfully debated. Arbitrariness is impossible to avoid in defining a poverty line, which essentially expresses a set of social norms. Consensus on such norms is not to be expected. The Tendulkar Committee explicitly recognised this and abandoned the earlier practice of anchoring the poverty line to a calorie norm. But its independently established minimum standards for various forms of expenditure were again ultimately arbitrary.

The Planning Commission has now constituted another Committee of Experts, which will redefine the poverty line in due course. But there is no reason to expect that the new poverty line will be universally judged as appropriate. Redefining the poverty line again and again is really a pointless exercise. It is much more useful to examine the sensitivity of poverty trends to changes in the poverty line. We can usefully study the alternative trends that emerge when we use different multiples of the current poverty line — 1.25 times the poverty line, 1.5 times the poverty line, 1.75 times the poverty line, and so on. In fact, the Planning Commission’s Press Note on Poverty Estimates, 2011-12 reports the results of an exercise of this kind but makes too little of this; it only points out that poverty decline is faster in the second period irrespective of the poverty line used. But the exercise also shows that the larger the multiple of the Tendulkar poverty line, the slower is the pace of poverty decline in both periods. A possible explanation is that the lower the poverty line, the larger is likely to be the percentage of the poor just below the line. It would be useful to systematically carry out such exercises in greater detail and analyse the results. We can then have a better understanding of what kind of poverty is showing what trends.

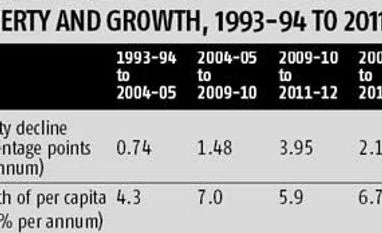

If we look at the full set of estimates (see Table) available, the first thing we notice is that, at the all-India level, the decline in extreme poverty was much faster during the period 2009-10 to 2011-12, when the pace of economic growth had slowed down, than during 2004-05 to 2009-10, when the pace of economic growth had been unprecedentedly rapid. The Planning Commission’s Press Note manages to hide this uncomfortable fact by focusing on the overall trend. It does mention that the whole reason for conducting a special survey in 2011-12 was that there was a drought in 2009-10. As such, it is likely that there was a temporary rise (or at least a slowdown in decline) in the incidence of extreme poverty in that year. Hence, the Note seems to be implying, the trend observed for the entire period since 2004-05 is truer.

As it happens, however, 2004-05 was also a drought year. Agricultural output declined by 1.6 per cent between 2003-04 and 2004-05, as it did by 1.4 per cent between 2008-09 and 2009-10. This means that the decline in the incidence of extreme poverty is being underestimated for the period to 2004-05 (because the terminal year was not normal) and overestimated for the period from 2004-05 (because the initial year was not normal). As such, no firm conclusions about the effect of higher growth on poverty can really be drawn from the comparison.

A look at state-level estimates gives us more reasons for caution. In Andhra Pradesh, the incidence of poverty apparently declined by 1.76 percentage points per annum between 2004-05 and 2009-10 and by 5.95 percentage points per annum between 2009-10 and 2011-12; yet the growth of per capita income was 7.9 per cent per annum in the first period and 7.4 per cent per annum in the second period. In Bihar, the incidence of poverty declined by 0.55 percentage points per annum between 1993-94 and 2004-05, by 0.18 percentage points per annum between 2004-05 and 2009-10 and by as much as 9.90 percentage points per annum between 2009-10 and 2011-12; the growth of per capita income in the three periods was 2.2 per cent, 8.7 per cent and 12.7 per cent per annum respectively. More such cases could be cited, but two points are already clear: that the decline in extreme poverty observed for the period since 2004-05 is vastly exaggerated, and that no systematic relation between the pace of poverty decline and the pace of economic growth can be found.

Where does all this leave us? We need to avoid sterile controversies and engage instead in serious analysis. There is nothing to be gained by constituting a Committee of Experts every few years to revise the poverty line. There is much to be gained by studying the effects of changes in the poverty line on time-trends in poverty. There is nothing to be gained by arguing about whether or not growth reduces poverty. There is much to be gained from serious analysis of the nature of the relationship between growth and poverty. This requires us to distinguish the effects of short-run fluctuations from those of growth. And the purpose of analysis is not to develop some simplistic view of how the rate of growth relates to the rate of poverty decline. The purpose is to understand what kind of growth has what kind of effect on poverty and why.

The author is, currently, Honorary Professor at the Institute for Human Development, New Delhi and, formerly, Senior Economist at the International Labour Office, Geneva

)