"Accident statistics assumes outstanding importance in dealing with the large and regrettable increase in the number of street and highway accidents…attention of the whole nation is sharply focussed on this increase"

You may be tempted to think that these statements are quotes from politicians and bureaucrats dealing with the Ministry of Road Transport and Highways following Gopinath Munde's tragic death in a road traffic accident in Delhi on June 3, 2014. Actually, the first is a quote from Lord Danesfort introducing a safety Bill in the British Parliament in 1932, and the second from a report on traffic safety statistics submitted to the US government in 1930. These reports suggest that death and injury due to road traffic crashes had become a serious concern in many European countries, North America and Australia by the 1930s.

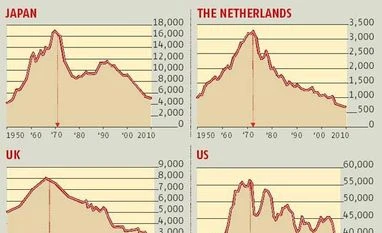

Many countries in these regions set up committees to suggest countermeasures to tackle the problem. The main recommendations of these committees included strict driving licensing procedures, safety education in schools, improving data collection and accident investigation, and heavier penalties for traffic lawbreakers. Most of these countries set up procedures for implementing these measures, but the death toll continued to rise for another 35 years. It is only in the 1970s that the trend starts to reverse in a few of these societies (see charts).

Unfortunately, this wealth of knowledge has not been internalised by most professionals, NGOs and politicians in India. We are still operating on the principles in vogue in the 1930s. Even more disappointing is the fact that policymakers have largely ignored the contents of these reports and policy documents. This, even though much of the modern information has been used to formulate several laws and recommendatory reports: the Motor Vehicle Act, 1988, the Sundar Committee Report to amend the Motor Vehicle Act (2011), the Sundar Committee Report on Road Safety and Traffic management (2007), 12th Five Year Plan sub-group on Road Safety and Human Resource Development (2011), and the National Transport Development Policy Committee Report (2014).

The recent clamour for new road safety policy gives the impression that unless new laws are made we will not be able to do much. In fact, if the provisions included in the 26-year-old Motor Vehicle Act (1988) are enforced, it should be possible to reduce death rates by more than a third. These provisions include compulsory wearing of helmets, speed control, enforcement of laws against drinking and driving, and implementation of motor vehicle safety standards according to international norms. The Act does not have to be amended to notify vehicle crash safety standards; the government can do that simply by a notification under the Central Motor Vehicle Rules.

Almost all the issues that need amendment of the Act as far as road safety is concerned are already included in the Sundar Committee Report of 2011. The proposals in that report bring it up to date with international best practices, and the report has gone through the due process of stakeholder consultations and feedback from state representatives. The committee debated the issue of the severity of punishments and sanctions in detail. It appears that if the fines mandated in the 1988 Act are adjusted for inflation they would be roughly similar to those in practise in western nations, taking into account the much lower per-capita income in India.

There is a consensus among experts around the world that deterrence is more dependent on the drivers' subjective perception of the probability of being stopped and fined than the actual amount of fine. On the issue of jail terms, again, there is a consensus that these should be awarded sparingly by a proper judicial process. Otherwise, many law enforcers start becoming more sympathetic to the violator and things get settled informally. Some experts have also suggested that judges start becoming more lenient if the punishments mandated are seen to be too severe.

There is great deal of public concern and even anger in view of the uncontrolled epidemic of injury and death on our roads. A few simple actions within the current laws can make a significant difference. For instance, the enforcement of seat belt and helmet laws should lower death rates annually by an estimated 25,000 people, drinking and driving another 20,000, speed control in cities and highways another 15,000 easily. A simple measure mandating motorcyclists to keep their headlights on in the daytime can save another 7,000 deaths or so. This relatively inexpensive measure has proved very successful in Malaysia and Singapore since it makes small vehicles more visible to large vehicle drivers in the daytime.

In the long-term, we will have to take international best practices of the 21st century more seriously and adapt them to our needs. Recent safety research from around the world suggests that road and street design influences driver and pedestrian behaviour very significantly. Our national highways do not follow international safety practices, our urban roads ignore the needs of the majority of road users - bicyclists and pedestrians. New laws and standards have to be enacted to make our roads much safer.

Currently, there is a great shortage of technical expertise to do so. There are absolutely no respectable jobs available for safety experts in the government at the central or state level at present. The latest National Transportation Development Committee report includes special chapters on safety and human resource development (http://planningcommission.nic.in). These suggest that unless we set up new institutions, institutional mechanisms for encouraging development of technical expertise, new research departments in national institutions and a National Transport Safety Board, safety on our roads will remain a distant dream.

The writer is Professor Emeritus at the Indian Institute of Technology.

These views are personal

)