The first of this two-part series analysed the potential economic impact of the second wave, noting that while the growth hit in the current quarter will be lower than last year at this time, the behavioural scars engendered by a vicious second wave could keep uncertainty elevated in the next quarter at least and, therefore, drive a more gradual recovery. Unsurprisingly, several GDP forecasts have been marked down towards 9 per cent for this fiscal year, which would leave the level of output about 8 per cent below India’s pre-pandemic path. How, then, should policy respond?

With a health crisis at the genesis of the current situation, it’s tautological to say that ramping up vaccinations is the “first-best” solution to tackling the crisis. It’s only when a critical mass of the population has been vaccinated that the insidious link between mobility and virus proliferation finally be severed.

But what should the complementary economic response be? Monetary policy was the prime mover last year and markets will inevitably clamour for that pedal to be pressed even harder. But quite apart from the fact that monetary conditions are already very accommodative and core inflation has averaged 5 per cent since the start of 2020, what’s less appreciated is the reduced efficacy of monetary policy in periods of elevated uncertainty. That’s because monetary policy ultimately relies on economic agents (households, businesses, banks) to act on the impulses it imparts. But when agents are faced with acute health, income and macroeconomic uncertainty, they often freeze into inaction (“the paradox of thrift”). So households don’t borrow, businesses don’t invest and banks don’t lend. This is evident in the evolution of bank credit over the last year in India. Despite negative real policy rates and falling real bank lending rates, credit growth has continued to slow all year long, likely reflecting these uncertainties.

The baton must, therefore, pass to fiscal policy. While fiscal policy cannot mitigate the health uncertainties it can help alleviate income and macroeconomic uncertainties. Stronger spending will not only boost activity but, in so doing, will reduce demand uncertainties for firms. Furthermore, income support (in cash or kind) along with public-investment-induced-job-creation can alleviate income uncertainties for households and thereby help catalyse the private sector.

Illustration: Binay Sinha

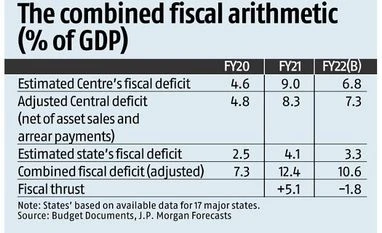

Recalibrating to new realities: Like last year, this year’s central and state budgets were presented before the Covid-19 wave and may understandably need to be recalibrated to fast-changing realities. After adjusting for asset sales and clearance of previous arrears (food and fertiliser) — needed to compute the underlying fiscal thrust — the combined fiscal deficit is effectively pegged to consolidate by about 2 per cent of GDP in FY22, compared to an expansion of 5 per cent last year (see table). Furthermore, this assumes strong budgeted asset sales targets are met. If they are not, the effective consolidation will be commensurately higher. On the states front, the consolidated budgeted deficit for FY22 — at about 3.3 per cent of GDP — is much below the 4 per cent ceiling that has been set. States also started the year with larger-than-expected cash balances — suggesting last year’s deficits and fiscal impulses will eventually be lower than presumed — and therefore barely borrowed from the market in April. All this would be understandable if the economy was poised to recover rapidly in FY22. But the second wave has clearly changed that calculus. With activity still expected to be 8 per cent below the pre-pandemic path at the end of this year, meaningful fiscal consolidation this year would make fiscal policy unduly pro-cyclical and potentially accentuate pressures.

Instead, the fiscal strategy may need to be recalibrated. In particular, the Centre and states should consider:

- Letting the automatic stabilisers play out, i.e., (i) not cutting expenditures if revenues undershoot on account of this new shock; and (ii) fully funding higher MGNREGA demand (if uptake for MGNREGA is weak because of virus concerns, cash transfers could be considered).

- Continue with free grain for the vulnerable till the effects of the second wave have waned.

- Double down on achieving budgeted asset sales targets, because this will provide space for more debt-free spending.

- Ensure that, to the extent that state capacity permits during a health crisis, budgeted capital expenditure targets are executed, given their multiplicative impacts on jobs and private investment.

- Encouraging states to go up to their 4 per cent fiscal deficit ceiling for this year.

All told, with the second wave throwing up new uncertainties that could constrain the recovery of the private sector, it would be desirable to use fiscal policy counter-cyclically again. As such, it would be perfectly understandable if the pace of fiscal consolidation is slowed this year or postponed for a year. On its part, monetary policy must do a “holding job” on rates and complement the fiscal by ensuring financial conditions don’t unduly tighten on account of fiscal recalibration or because of increasing normalisation pressures around the world.

Making space while the sun shines: All of that said, given India’s expansive starting points, any prescription to use policy counter-cyclically for a second straight year must be accompanied by a determined and credible consolidation path in the following years, to preserve macroeconomic stability. Counter cyclicality must be symmetrical: supporting activity in times of a shock, but then quickly retreating to create space when vaccinations reach a critical mass and the recovery becomes more entrenched.

India’s Debt/GDP is likely to hover close to 90 per cent of GDP at the end of this year and ensuring this ratio does not monotonically rise in the coming years must be a key objective of macroeconomic policy. Counterintuitively, the evolution of medium-term growth will be absolutely crucial to debt dynamics, as we have previously demonstrated. If nominal GDP settles at 10 per cent in the medium-term, Debt/GDP will first stabilise and then gradually soften. In contrast, if nominal GDP were to settle closer to 8 per cent, Debt/GDP will keep rising monotonically in the coming years, raising the spectre of macroeconomic instability.

For this reason, it’s important that fiscal policy attempts to minimise more hysteresis and scarring this year. But supporting growth will go beyond counter-cyclical policy. It will need to entail reforming the financial sector and ploughing ahead with public investment — an important and welcome start of which was made in this year’s Budget — along with several factor-market reforms.

Growth support apart, stabilising debt dynamics will also require progressively normalising the primary deficit in the coming years after the crisis-induced spike. If fiscal consolidation is slowed or postponed this year, a more concerted effort will be needed from next year onwards, underpinned by tax and revenue reforms, and situated in a new medium-term fiscal anchor.

Similarly, monetary policy has been very accommodative over the last year. But as the economy recovers, it will be important to ensure real policy rates are pulled out of negative territory and the flood of interbank liquidity is progressively normalised to create space for future shocks. Once the recovery takes hold, the RBI must rebalance the weights in its Taylor Rule back towards the inflation target.

Second waves have increased policy challenges around the world. Increasing the vaccination pace must undoubtedly be the first line of defence. But getting the fiscal-monetary mix right must closely follow suit. This will not be an easy balance. But then, this is no ordinary crisis.

Sajjid Z Chinoy is Chief India Economist at J P Morgan.

All views are personal. The first part of this two-part article appeared on May 24

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)