In the public sector undertaking (PSU) universe the maharatna companies are those that have the bluest blood running through their veins. They have larger balance sheets than the navratnas and the mini-ratnas, that fall below them in the pecking order. And they are given more autonomy — being free to decide on investments of up to 15 per cent of their net worth. There are eight of these — Bharat Heavy Electricals Ltd (BHEL), Bharat Petroleum Corporation Ltd (BPCL), Coal India Ltd, GAIL (India) Ltd, Indian Oil Corporation Ltd (IOC), NTPC Ltd, Oil & Natural Gas Corporation Ltd (ONGC) and Steel Authority of India Ltd (SAIL).

This elite set can hold its head high among all Indian companies — not just PSUs. Business Standard data for FY17 —the FY18 numbers are not in yet — shows five of the eight are among the top 10 most profitable companies in India and seven of these eight make it to the top 25 in terms of sales, with all eight in the top 35.

The eight maharatna companies have sent out their AGM notice and annual report for the just closed financial year. Let me focus on just the one aspect namely their boards. Two things stand out when reviewing the board tables — its composition and directors’ tenure.

These eight maharatna companies have 123 directors on their boards. Forty seven of them are executive directors. With a pan-Indian spread of manufacturing facilities more often in the sleepier districts, six per company is par for the course. At 38 per cent this is a larger percentage than private corporations. Most private sector companies, but not all, have two or three executive directors. The exceptions — with five or more are usually those whose organisation structure and family trees merge. These tend to be the smaller companies, where the patriarch still casts a long shadow.

Each ministry by habit has two of its nominees on the board. We have 15 representatives — SAIL having only one for now. Of the 61 remaining, 29 — nearly half — are retired civil servants. Of these, the bulk are retired IAS officers (15) and the balance drawn from the foreign service, revenue service, economic service and forest service, among others.

Put differently, 44 of the 76 non-executive directors or 57 per cent of the non-executive directors, are either currently working or have worked for the government of India. While some will no doubt have domain knowledge in an area, most are generalist, and the skill they bring in terms of the shareholders notice, is ‘understanding and dealing with the government’. This preponderance of bureaucrats has one major downside: It leads to group-think. Groupthink occurs when a group with makes sub-optimal decisions because they value cohesiveness over critical evaluation. Individual’s typically refrain from or may in private express doubts or disagreement with the consensus.

The unanswered question is why a government company needs someone to be able to deal with itself. Isn’t this why these companies have government nominees on their boards?

Then there are a handful of chartered accountants (10), academicians (nine), lawyers (five). The balance eight are drawn from the private sector and consultancies and even those that bankers classify as ‘politically exposed persons’.

The only worthwhile takeaway is the presence of academicians on boards —they are under-represented in the private sector. We need far greater interaction between industry and the academic world. I will not enumerate the various reasons, suffice to say, such links are needed to help bridge the skill gap between those that graduate and those industry recruits.

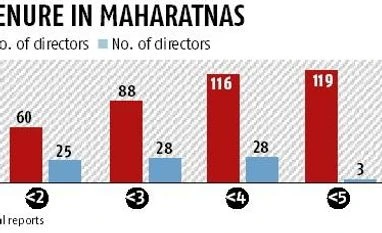

Composition apart, equally disquieting is the tenure of the various members of the board, which is given in the chart (Board tenure in maharatnas).

That only four of these directors have been on the board of their company for more than five years also suggests that there is little or no institutional memory. True eight companies do not make an Indian summer, but these eight are PSU royalty. They get invited to sit on the high table, are the ones that are showcased, those that the government is the proudest of. And yet, there is no one in there thinking about the long-term.

For boards, in aggregate, it is worthwhile asking who has the domain knowledge to question business assumptions and challenge management. Who then can get into the skin of the company? Who has a view about the rhythm of the industry? Who is best place decide about the long term? The ministry nominees? They are not on the board or in the Ministry for long enough to understand the business dynamics. The executive directors? Maybe, but how much authority do they really have? The independent directors? There are no industry leaders, no one who has built or run a meaningful business, or has acquired companies overseas or walked down the untrodden path. With a narrow set of skills and an average vintage of under two years, the board as a whole, is not equipped to take a long-term view.

Contrast this to the private sector. They do bring in civil servants for ‘knowledge of the working and dealing with the government’ that they bring, but in right proportion. In addition, they also appoint for diversity and skills. The average tenure of board members is 9.48 years and for executive directors 13.27 years — admitted, at 500 companies it is a far larger sample size.

That these maharatna companies still dominate the profit charts is because they are monopolies. Open them to competitive pressures and see how many will hold their own — BSNL, MTNL, Air India, Hindustan Photo Films, Hindustan Copper, Hindustan Fertilizers. Even SAIL — though still a maharatna and once towering above all other steel companies — is not even the largest player in the sector.

No doubt the PSUs face unique challenges that make their governance more complex than in the private sector. They have diverse objectives both commercial and social, conflicts of interest — since the parent ministry is both the administrative owner and regulator, and really protracted decision-making. But paying mere lip-service to the existing framework is the surest way to lose the battle in the long term.

The author is with Institutional Investor Advisory Services. Twitter: @amittandon_in

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)