A solar panel can be a good friend to a specific kind of shade-loving crop. A typical “agrovoltaic” or “agroPV” installation involves solar panels at a height of a few meters from the ground sheltering crops underneath. The same piece of land thus produces crops, and power. What panel and what crops gel well together is currently a subject of global interest.

India has embarked on its own version of “solarising” agricultural farms, and this could possibly change the dynamics of the whole power sector. Its ambitious programme for solar farms involves multi-gigawatt installations via the PM-kusum scheme, which is targeting 3.5 million solar pumps across the country (of which 1.5 million would be grid-connected), as well as installation of small solar plants (up to 2 megawatts) on the edge of farms, on barren/fallow land, supported by subsidies.

That could translate to over 30 gigawatts of new solar. As of March 2020, before the pandemic hit, 1,000 megawatts of such solar plants were sanctioned, as well as about 240,000 solar pumps, according to data provided by the renewable energy minister in response to a question in Parliament. Approvals have started picking up pace again, as lockdowns have eased.

There is a lot more that can be done to power farms — and farming infrastructure — cost-competitively in a country that has such abundance of sunlight.

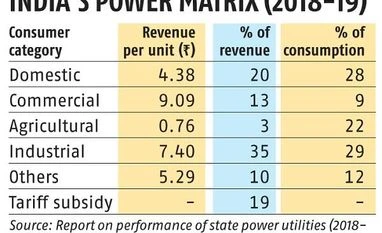

Most farmers in India get subsidised power, which is priced at a fraction of the cost of supply. In Maharashtra, for instance, agricultural consumers account for 30 per cent of the power sold while they bring in less than 5 per cent of total revenue. The revenue per unit from this category of consumers is about Rs 1, while the cost of providing power is about Rs 7.50.

Solar on every farm

A proposal to set up (and maintain) solar power plants in the state with batteries and street lighting for 25 years — at a compelling tariff — has been put forward by Energy Efficiency Services Ltd. This would involve zero investment by the state utility (MSEDCL), and help slice away a good part of its revenue gap.

“We are offering a rural development package now. We can bundle the decentralised solar plant with lithium-ion batteries, and also provide street lighting for a levelised tariff of less than Rs 4 [per kWh],” Saurabh Kumar, EESL’s executive vice-chairman, told BloombergNEF. “That would mean solar on every Indian farm, and saving of over $2 billion in a state like Maharashtra.”

All MSEDCL has to do is provide land for the solar plants — which in many cases it has available near its substations.

“We are talking to multiple state governments for this scheme [called convergence]. Their response has been extremely positive. We are also trying to see how this can be integrated with the Kusum scheme,” Kumar added.

In Andhra Pradesh, as Business Standard reported, the government plans to develop 10,000 megawatts of solar capacity “to meet the requirements of agriculture sector, for which the government has promised to provide nine hours of free power per day entirely during day time,” without adding to the burden of the state distribution companies.

There may, however, be a question mark over the interest of developers in setting up projects in a state that has been attempting to renegotiate power purchase agreements for projects already commissioned.

Solar-agriculture meshing

Maharashtra has also been experimenting with conventional agroPV. According to an analysis by Fraunhofer ISE of the Paras agroPV project of Maharashtra State Power Generation Company with partner KfW, land use efficiency almost doubled. This is similar to the trends that are being seen in the rest of the world. Yields of some crops increase under the shade of panels, especially when the sunlight is particularly intense.

China, France and Massachusetts in the US offer financial incentives for agroPV. Germany’s Baywa r.e. recently completed a 2.7 megawatts solar installation above raspberry plants in the Netherlands, using specially designed semi-transparent modules, “allowing sunlight sufficient for the plants to pass through, while at the same time protecting the crop from hail, heavy rain and direct sunlight.” It is now working with different varieties of fruit and panels.

Germany’s Next2Sun has been using bifacial panels (which generate power from both sides) for vertical installations on farms. Meanwhile, there is already talk of pilots on automated farming, where agricultural machinery would be integrated not only with solar, but with robotics, automation and artificial intelligence to take us to next-generation agriculture. Expect to see a lot more experimentation and innovation in agroPV.

The writer is editor, global policy, for Bloomberg New Energy Finance; vgombar@bloomberg.net

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)