The recent tariff subsidy bonanza announced in New Delhi for residential consumers of electricity — of up to 200 units/month — might gratify the public, but goes against economic rationale. Instead, tariff rationalisation and targeted subsidy would go a long way in sustaining the reform momentum started by the Ujwal Discom Assurance Yojana (UDAY). UDAY focused on turnaround of distribution companies (discoms) through cost reduction and improvement in operational efficiency. While it has improved some operational and financial aspects, discoms remain utterly fragile.

The UDAY dashboard shows reduction in aggregate technical and commercial (AT&C) loss to about 22 per cent. Cost recovery has improved, too, with the gap between average cost of supply (ACS) and average revenue realised (ARR) narrowing to Rs 0.40/unit as on September 2019.

However, going by the scheme’s current performance, the Centre is likely to miss the final target of reducing ACS-ARR gap to Rs 0/unit, and AT&C losses to 15 per cent by 2020. The gap is significantly high for some states (Rajasthan about Rs 1.25/unit, Bihar about Rs 0.93/unit, Andhra Pradesh about Rs 0.67/unit, Tamil Nadu about Rs 0.78/unit, and Uttar Pradesh about Rs 1.1/unit.

Indeed, the overall gap translates to approximately Rs 62,482 crore of loss annually. This is over and above “regulatory assets” worth around Rs 1.35 trillion created on the balance sheets of discoms because of previous gaps.

As things stand, tariffs do not reflect the cost of supply for some consumers. There is little to no improvement in cross-subsidy levels for industrial and commercial consumers. These tariffs are among the highest in the world, which impacts the cost competitiveness of industries.

As per the Report on “Roadmap for Reduction in Cross-Subsidy” by the Forum of Regulators, cross-subsidy for industrial consumers in Gujarat, Tamil Nadu, Rajasthan, Punjab, Maharashtra, Karnataka, Uttarakhand, and Madhya Pradesh was higher than the ceiling of 20 per cent set by the National Tariff Policy (NTP). The NTP 2006 and 2016 prescribe criteria for cross-subsidy, envisaging a gradual reduction. In many cases, industrial and commercial tariffs are 50-100 per cent above the 120 per cent ceiling prescribed.

And that’s not all. The cost of supply is still way higher for low-tension, or agricultural and domestic consumers, compared with high-tension, or industrial and commercial consumers. That is because the more the money needed for last-mile connectivity, the greater are the losses incurred. Therefore, cross-subsidy levels based on “actual” cost — and not average cost of supply — is very high and unsustainable.

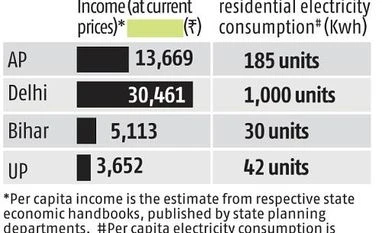

Delhi has one of the highest per capita incomes and highest electricity consumption. It also has perhaps the best quality of electricity supply. Do consumers there even need the subsidy?

Delhi also has a cushion of fiscal surplus, which makes such unnecessary doles “affordable” — something states with low per capita, poor quality of supply, and constrained fiscal health can ill-afford. Indeed, as the table (How they stack up) shows, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar — with poor capita income and erratic supply — are among the worst off.

The total subsidy and cross-subsidies of discoms at about Rs 1.2 trillion in 2018. Such high levels, coupled with ACS-ARR gap and regulatory assets, would render the power sector powerless, impacting fresh investments in generation and transmission, as well.

Not all is lost, though. Three proactive measures can address the situation:

• Calibrated tariff hikes: Just like diesel prices were deregulated with a monthly increase of Rs 0.50/litre, electricity tariffs could also be tweaked up monthly/quarterly for at least three years, based on predetermined percent that may include some realistic efficiency inbuilt. Some may argue that this amounts to passing on potential inefficiencies of the distribution entity to the consumer. But the fact is, there is a large ACS-ARR gap, accumulated losses, and piled up regulatory assets that need to be cleared. This would be subject to regulatory scrutiny at the end of the three-year period.

• Guidelines for cross-subsidy reduction: To reduce the cross-subsidy on industrial and commercial customers going forward, state regulators need to implement reduction in cross-subsidies and removal of political inertia in increasing domestic and agricultural tariffs gradually. Ultimately, subsidy (if required), directly must go only to deserving consumers, with low per capita income or below poverty line.

• Direct benefit transfer (DBT): To plug leakage and ensure targeted subsidy, DBT could be implemented. States may replicate in the power sector what the Centre successfully did with liquefied petroleum gas subsidies.

Sans tariff rationalisation and targeted subsidy, all other reforms efforts —including open access, retail-supply separation, and even public-private partnership/privatisation — will not yield the desired results.

The author is senior director, CRISIL Infrastructure Advisory

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)