On March 7, the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India (IBBI) published on its website a draft framework that will govern the process of making regulations by the IBBI. The draft makes three substantive proposals to enhance the robustness of IBBI's regulation making process. First, the IBBI will conduct a public consultation process before making every regulation. It sets out the details of this process, including the information that it will publish for aiding the public consultation and at the time of issuance of the final regulation. Second, the IBBI will conduct an economic analysis of all the proposed regulations. Such economic analysis will cover the costs and benefits of its regulatory proposals, and will be published as part of the consultation process. What’s more, the IBBI has supported this draft with a note analysing the costs and benefits of democratising the regulation making process of a regulator. Finally, the draft proposes a review of its existing regulations every three years, for evaluating if they need to be amended or repealed, keeping in view their objective, outcome, experience and global best practices.

This proposal of the IBBI is of great significance. For the first time in the history of the Indian administrative state, an Indian regulator has explicitly committed itself to a process-oriented methodology for making regulatory interventions. Seen in this light, the draft sets new standards of regulatory governance in India.

With the rise of an administrative state, the behaviour of economic actors is largely dominated by the rules made by specialised regulatory agencies, as opposed to the Parliamentary law. For instance, the Securities and Exchange Board of India (Sebi) Act, which governs the Indian securities markets sets out the framework within which Sebi, a specialised regulator, must exercise its powers. However, how brokers will be regulated in their day-to-day affairs, how must they apply for licences, how must they interface with consumers, etc is entirely dictated by delegated legislation made by Sebi. Therefore, the process through which such delegated legislation is made, directly impacts all economic activity in the specific segment to which it applies.

Some countries have an overarching sector-neutral framework that governs the process of making delegated legislation by any regulator. For instance, in the US, the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) governs the manner in which federal agencies will engage in rule-making. However, in the absence of such a framework in India, the quality of the regulation making process by Indian regulatory agencies varies from regulator to regulator.

To begin with, the Indian regulators make regulatory interventions through various instruments of delegated legislation. For instance, a 2016 Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research (IGIDR) working paper that empirically analyses the quality of regulation making processes across four Indian regulators — namely, the Reserve Bank of India (as the banking and foreign exchange regulator), Sebi (as the securities markets regulator), Telecom and Regulatory Authority of India (Trai) (as the telecom regulator) and Airports Economic Regulatory Authority of India (AERA) (as the tariff setting authority for airports) — finds that during the study period of January 1, 2014, to April 30, 2016, Sebi made regulatory interventions through 51 regulations and 122 circulars. During this period, the RBI made regulatory interventions through 48 regulations and 1,016 circulars respectively. On the other hand, Trai's regulatory directives were issued through regulations, orders and directions, and AERA’s directives, mostly tariff-related, were confined largely to orders.

While the delegated legislation termed ‘regulations’ undergoes ex-post Parliamentary scrutiny, other forms of delegated legislation, often termed ‘circulars’ or ‘directions’, do not undergo such scrutiny, even if they make the same extent and intensity of intervention as ‘regulations’. This is because the laws governing such regulators confer general direction-making powers on them. This continues to remain a possibility even for the IBBI. Therefore, if the IBBI makes regulatory interventions through circulars or other instruments, then it will end up diluting the robustness of the process that it proposes through the draft.

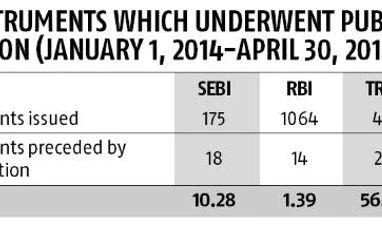

The 2016 paper further shows the proportion of regulatory directives that underwent a public consultation process before they were operationalised (see Table). The table demonstrates the extent to which one regulator’s process for making regulatory interventions may differ from that of another. While close to 56 per cent of the regulatory interventions made by Trai underwent a public consultation process, the corresponding numbers for Sebi and RBI were at 10 per cent and 1 per cent respectively.

The Supreme Court, in a 2016 judgment striking down a Trai regulation penalising telecom operators for call drops on their network, had highlighted the importance of an effective public consultation process by regulators. Reprimanding Trai for not giving reasons for rejecting stakeholder comments received in the public consultation preceding the call-drop regulation, it underscored the need for an APA-like law in India that mandates executive agencies to follow a notice and comment process before the issuance of delegated legislation. However, the judgment explicitly held that regulators need not follow natural justice (including the right of the public to be consulted) in the performance of their legislative functions, unless their respective governing statutes specifically impose such an obligation. This effectively meant that in the absence of a specific obligation in the law to hold public consultations, an Indian regulatory agency could dispense with such due process before issuing regulations.

While the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 specifically requires the IBBI to ‘specify mechanisms for issuing regulations, including the conduct of public consultation processes before notification of any regulations’, it is commendable that the draft put out by the IBBI goes beyond public consultation, by also building in the requirements of an economic analysis of every regulation and the regular review of existing regulations. The standards that the IBBI imposes upon itself in the draft are in line with the report of the Financial Sector Legislative Reforms Commission, which made extensive recommendations on reforming regulatory governance standards for Indian financial sector regulators. Importantly, adherence to these standards will only enhance the quality of the regulation making process, and ensure that the regulations are not only forward-looking, but also outcome-oriented. Finally, the draft is indicative of a mature regulatory institution that is open to self-evaluation and critique.

The 2016 paper referred to in the article was co-authored by the writer with Anirudh Burman

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)