The ill wind of rampant violence against students and faculty of Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) by masked hoodlums on January 5 took place in some of the most miserable weather the capital has known, with temperatures plummeting to the coldest in decades.

If that was a barometer of national politics, then a bitter winter of discontent augurs a dangerous spring for the Narendra Modi-Amit Shah ruling establishment and their Hindutva-fuelled followers.

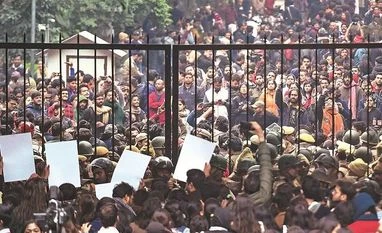

From the blur of images of Bloody Sunday — students’ union President Aishe Ghosh’s bandaged head from wounds inflicted, Deepika Padukone’s flying visit, hundreds of protesting students gathered at the gates — some stark facts stand out. They suggest the complicity of forces on high behind the orchestrated attacks. A large police force turned a blind eye to several hours of mayhem in the students’ hostels, the street lights conveniently went off, and the vice-chancellor — a government appointee — fiddled, like Nero, as his realm burned.

To this day he has not been held accountable for his failure to restore order. Moreover, the assailants have not been tracked. And, bizarrely, FIRs were filed against Ms Ghosh as the agent provocateur rather than the sinister untraceable attackers. As a Centrally-funded institution, JNU has been very much in the government’s line of fire for some time, from February 2016 in fact, when Kanhaiya Kumar, its former students’ president, was arrested for sedition and criminal conspiracy for allegedly voicing anti-national slogans, a charge he denied.

Like his successor, Ms Ghosh, Mr Kumar belongs to the Leftist union and has long been denounced by the prime minister, home minister and the BJP’s students’ union as the “Tukde Tukde Gang” — by now a rather jaded phrase that started out to describe a bunch of “anti-national” students hell-bent on shredding the country but is now applied to anyone politically opposing government policy or ruling party ideology.

Like that other shop-soiled appellation “Khan Market Gang”, the label can be embarrassingly ironic. Two pillars of the Modi government, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman and Foreign Minister S Jaishanker, are former JNU students, and have had to issue cringe-worthy assurances that in their student days there was no “Tukde Tukde Gang” and they were engaged in blameless intellectual capacity-building rather than involvement in the university’s established Left-liberal leanings. (The two are not necessarily mutually exclusive, indeed they often go together in places of higher learning.)

Judging by the spillover of students’ protests nationwide in expressions of solidarity for the JNU violence, infiltrating campuses and tampering with the aspirations of a restive youth population desperate for degrees and hungry for jobs can have unforeseen consequences. It is not the same kind of control enforced by military might in the lockdown in Kashmir or the passing of the Citizenship Amendment Act through parliamentary legislation. Opposition to both has been swiftly and peremptorily dealt with.

Mr Modi’s authoritarian streak is sometimes compared to Indira Gandhi’s rise to absolute power. If so, the triggering of a students’ agitation carries a fateful echo from the non-so-distant past.

In 1971, fresh from victory in the Bangladesh war and a triumphant election, Mrs Gandhi was at the very zenith of her power. Her international prestige was high and her command of the party and state governments untrammelled. Yet it was precisely her tightening grip on controlling levers that made things go wrong — the lightning rod being the students’ unrest in Bihar and Gujarat.

In her incisive political biography Indira Gandhi: Tryst with Power (Penguin; Rs 399), the writer Nayantara Sahgal gives a detailed account. It was small things (such as JNU students recently protesting a hike in hostel fees) that set off the conflagration. In January 1974 a student revolt against food prices in engineering college hostels in Ahmedabad and Morvi erupted into a citizens’ movement against scarcity and misrule. That same year students of Patna colleges held protests demanding educational reform. In both cities there were police beatings at barricades, arrests, and bloodletting. Thence forward the story of Jayaprakash Narayan’s emergence as a galvanising force, Emergency rule and Mrs Gandhi’s fall in 1975 is well-known. “In her grasp of the nuts and bolts of the machinery of power,” observes Ms Sahgal, “Indira Gandhi installed a strategy of command that depended entirely on personal loyalty”.

The student uprisings of 1974 were not abetted by WhatsApp wars, Twittermania, or a body of outspoken supporters from the film world. The smashings and thrashings at JNU are right in our face; they force the most passive observer to take sides. As a pan-Indian (to use that overused but indefinable phrase) community, university students everywhere are the same. Everyone either knows a college-goer, or was one, or, in the basic human desire for self-improvement, hopes to become one. An ill-educated driver I once had, a runaway from rural Bihar, used to regretfully intone: “Sir, vidya se badi koi sampati nahin hai” (Sir, there is no greater wealth than education).

New Delhi’s rulers should be alert to lighting a dangerous tinderbox. Besides, the city-state will elect a new government on February 11. The voters will factor in JNU’s Bloody Sunday.

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)