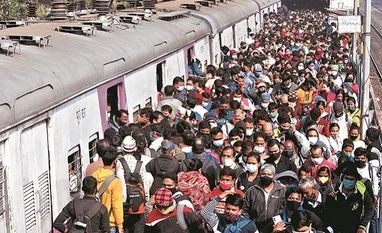

The basic point is that increasing numbers make it easy for governments to tax and spend, and prop up aggregate growth figures. The dangers of a declining population are visible in countries like Japan or Russia, beset by problems from macroeconomic imbalances to empty villages. But the challenges that a vast population brings in are also easy to see. The weight of numbers on man-made infrastructure is not difficult to understand. Even more worrying perhaps is the pressure put on natural resources. The recent and alarming subsidence of a pilgrimage town in the Himalayas reveals the degree to which increasing numbers and also growing aspirations create challenges for the sustainability of India’s natural habitats. Nor is this necessarily a moment to savour unless there is certainty that India’s abundant human resources match in quality what they have achieved in quantity. Indian public policy must refocus itself on the challenge of improving the quality of human resources. This moment of demographic outperformance must be seized if India is to become an upper-income country. Once it starts aging, it will be too late.

This epochal moment is also one where the broader contours of geopolitical and geo-economic power over the next century could and should be considered. China’s great shrinking has begun; the Lancet projections indicate it will eventually plateau by the end of the current century at a population of about 730 million, hundreds of millions fewer than that of India, which will still have over a billion people. For that matter, current projections are that Nigeria will have more people than China by 2100, while the population in the United States will grow marginally and not shrink. Expectations that this will be China’s century must deal with the likelihood that it will also have to cope with the problems of an aging society at the same time it makes a bid for global power. There is one final lesson to be drawn from this turn of events. India’s ascent to top place took a lot less time than expected. This is because demographic trends often seem to gather momentum faster than the best projections made a decade in advance. In other words, India’s own period of population shrinkage may not be as far in the future as previous estimates had supposed.

To read the full story, Subscribe Now at just Rs 249 a month

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe To BS Premium

₹249

Renews automatically

₹1699₹1999

Opt for auto renewal and save Rs. 300 Renews automatically

₹1999

What you get on BS Premium?

-

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

-

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

Need More Information - write to us at assist@bsmail.in

)