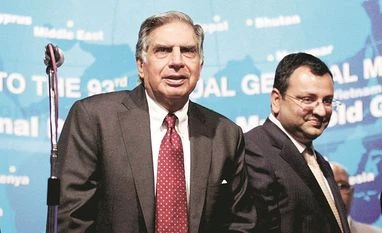

The last few weeks have witnessed a most unedifying spectacle in Indian corporate history. The House of Tata — a doyen of probity — has been shamed by its incomprehensible corporate governance. In the war of public words between its two most recent chairmen, there have been no winners.

Tata’s brand equity, once over US $5 billion, is negative. The reputation of Ratan Tata, once seen as India’s premier businessman (for reasons that elude thoughtful minds) is in shreds. That of Cyrus Mistry has been ruined before he had a chance to prove what he was made of. Sadly, he firewalled himself with people of dubious ability who did not mesh with Tata’s odd corporate culture.

This tussle between two bull elephants, whose egos are wounded beyond either’s capacity to bear, will result in continued bloodletting till denouement. Only the destruction of what remains, will end the gory spectacle. Is this gladiatorial contest, of Caligulic proportions, necessary for the protagonists to satisfy the bloodlust of a public audience watching a soap opera played out in real life? In the process, the reputation and capability of Tata operating companies is being damaged; whether that will be irreparable depends on how soon this absurdity ends.

Government and influential large shareholders seem unable to put a stop to this tragedy, though they have been approached by both sides. What is inexplicable is the role that the creditors to the House of Tata have played so far. Heads of public and private banks with exposure to Tata have claimed they are monitoring the situation. But, is diligent surveillance enough? There is an enormous amount of stakeholder damage being done by this feud which neither side can win — except in a Pyrrhic sense.

The market cap loss to shareholders of the listed Tata companies is between Rs 0.8 and 1.0 trillion (lakh crore) or about US $15 billion; for a multinational conglomerate whose top line is over US $100 billion. The bottom line reflects a return on capital that is sub-standard in the Indian (and global) corporate world. The loss in market value affects millions of people who hold shares in Tata companies. It affects pension funds whether public or private. It affects Indian taxpayers who are put at risk because of loans made by state-owned banks to the Tatas. It affects shareholders in private banks that have large loans to the Tata Group at risk. It affects FIIs with stakes in Tata companies.

More From This Section

Clearly, what is happening at the group is not fraudulent in the sense perpetrated at Satyam. That inspired the Union government to set up a turnaround committee chaired by Deepak Parekh. It resulted in the sale of Satyam to Tech Mahindra and its recovery thereafter. It was one of the more successful public interventions in corporate history from which lessons can be learnt and applied in the Tata case.

Though the Tata case is not that of fraud, many of the allegations levelled by Cyrus Mistry come close to it. He has outlined several examples of Ratan Tata’s personal preferences and pet projects resulting in a waste of shareholder and creditor money. If examined forensically, and proven to be a cavalier use of money, then Ratan Tata and the operating companies involved need to be held to account.

With debt of US 40 billion and effective NPAs (taking into account ever-greened loans) of US $5-6 billion, the creditors of Tata — which comprise (a) state-owned banks, (b) private Indian banks, (c) foreign banks registered in India and (d) foreign banks that have lent to Tata abroad but are not registered in India — need to form a Tata Group Creditor Consortium (TGCC) to intervene in stopping this war and preventing more damage being done.

TGCC should have two senior representatives from each of the four groups identified above, along with the heads of Sebi, NSE and BSE. It should be chaired by someone like Deepak Parekh or Aditya Puri. Its immediate task should be to bring to an end public open letters by Ratan Tata and Cyrus Mistry. It should also look into: the complex relationships and interlocking shareholding arrangements among the Tata Trusts, Tata Sons, operating Tata companies, and the peculiar colonial managing agency arrangements that have made the Tata Group and its individual operating companies almost intractable.

TGCC should force the restructuring of Tata company boards along cleaner lines to ensure that each operating company has a capable management team to ensure its survival or turnaround. It should consider the roles of directors from Tata operating companies on the boards of other Tata companies and their impact/influence on the role of the independent directors on these boards.

The performance of independent directors on Tata boards in resolving difficult issues has been far from exemplary. Indeed, the calibre of independent directors on Tata boards makes one wonder what the criteria are for choosing them, other than pliability in doing Rata Tata’s bidding. In the case of directors of the Tata Trusts and Tata Sons, those over the age of 70 seem to be past their sell-by date. Those younger, especially from abroad, lack proven competence and suffer from an overdose of pliability.

Finally, TGCC needs to establish a clear code of conduct of how listed Tata companies should operate as independent entities, in charge of their own destinies and as responsible borrowers in their own rights. It should consider whether the Tata Trusts, Tata Sons or operating Tata companies should be treated as promoters, or institutional investors, for the sake of clarity and probity.

As things stand now, it is impossible to determine whether any future executive chair of the Tata Group could do that job without also being Chairman of the Trusts and of Tata Sons. In acting as he has, Ratan Tata has poisoned the chalice for any future Chairman, especially if he continues to call the shots by remote control as he has so far.

The author is chairman, Oxford International Associates Ltd

READ OUR FULL COVERAGE OF THE TATA-MISTRY BOARDROOM BATTLE

READ OUR FULL COVERAGE OF THE TATA-MISTRY BOARDROOM BATTLE

)