On the results night in 1977, Prannoy Roy and a few of his associates sat hunched over a radio in their barsati. “AIR (All India Radio) was still operating under the fearsome shadow of the Emergency. As the results began to come in, AIR persisted in presenting a falsely ‘balanced’ picture,” writes senior journalist and NDTV founder Roy in his new book, The Verdict: Decoding India’s Elections, co-authored with market researcher and pollster Dorab R Sopariwala. But even the limited information revealed to them “that there was a sweep… in favour of the Janata Party”. Wine bottles were already being uncorked. The Emergency era, the lowest point in the history of the Indian democracy, was drawing to an end.

In their book, Roy and Sopariwala claim that 1977 marked a shift from the “pro-incumbency” phase of the previous 25 years — the first general elections were held in 1951-52 — to an “anti-incumbency” phase. “Dorab coined the term,” says Roy. “I don’t remember,” replies his co-author. The duo had analysed data from 78 state Assembly elections for the first phase (1952-77) and 93 elections for the second phase (1977-2002). “Now, 2002-19, we are in a 50-50 era, where governments have a 50 per cent chance of being re-elected, if they perform,” they write. The message from the voter is clear: “perform or perish”.

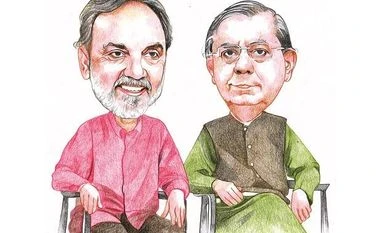

When I meet Roy and Sopariwala (in March), everyone is eagerly waiting for the Election Commission (EC) to announce the dates for another election. I meet the duo at Roy’s cabin in the NDTV office in south Delhi. The small L-shaped room has glass windows. From where I sit, I can look out at the parking lot of the building complex. On one wall of the cabin hangs a large, rectangular TV playing eight news channels. On another wall, directly over Roy’s neat desk, hangs another large flat screen playing NDTV. Both are mute. On the desk is a small Indian flag.

This book has taken a long time to write, claim the authors. “Like true Librans, we are perfect procrastinators,” says Sopariwala. “But he (Roy) is the king of them all.” Roy agrees. “If the elections were not around the corner, we would never have finished it,” he says. “There were many late nights, staying up till 3-4 am to meet a deadline. I work best to a deadline.” Roy adds that he had, however, finished his PhD in three years flat. “That was to a deadline, right?” I ask. Roy demurs: “In Delhi University, six-seven years was the norm.”

I am curious how Roy, who did a PhD in economics, and Sopariwala, a graduate from the London School of Economics, got involved in the profession of election journalism and poll forecasting. “It is such an aphrodisiac,” says Sopariwala. “If you are in India, you are always watching elections. I am deeply interested in politics, though not as a participant.” Roy says he was not interested in politics. “But I am an election junky,” he adds. The very nature of Indian democracy and how elections are conducted — and consequently forecasting and analysing polls — has seen a sea change over the past 40 years. “You could call this one (2019) the WhatsApp election,” says Roy.

At this point, Roy and I decide to go for some coffee; Sopariwala sticks to water.

One of the most important factors for elections anywhere now is the internet and social media. After the Cambridge Analytica scandal (2018), governments all over the world and even in India are demanding more accountability from social media giants such as Facebook and Twitter for information spread on their platforms. Sopariwala says this is not such a significant factor for a pollster. “We are trying to analyse the output (the vote), not the input,” he says. “As long as the voter is not lying about whom they are going to vote for, how does it matter what influence is working on them?”

Roy says the influence of the internet is an added factor for those analysing elections. “The great thing about the internet is anonymity,” he says. This is a subject they also write about in their book: “While anonymity is at the very core of the internet, in the ‘rarest of rare cases’ — where the aim of the message is to create violence, killing or rape — the anonymity needs to be sacrificed.” Roy adds that this power should reside only in the judiciary and not in the governments.

If not the internet, how influential are opinion poll or forecasts, like the ones that Roy and Sopariwala do? “Not in the least, according to the research done in this area,” says Roy. “It has no effect on the voters. It affects the morale of party cadres.” And how politically motivated are such polls? “I doubt that there is any political motivation to polls that are close to the election,” says Roy. “If a pollster puts out wrong data, he would look like a fool when the results come out. There is in fact a 97 per cent strike rate among Indian pollsters in predicting the right winner.”

There are other challenges as well — especially for the EC. “Mainly logistical,” says Sopariwala. For instance, 21 million women are missing from the electoral roles. “That’s more than the number of women in Jharkhand,” says Roy. (According to the 2011 Census, Jharkhand has 16,057,819 women.) Roy and Sopariwala are arguing for any women who can prove that she is above 18 years old to be allowed to vote at her nearest booth. “And, then we can make a genuine effort to include many more of them in the next election,” says Roy.

The focus of this election will be women in villages, they claim, adding that since 1971, when the number of rural women turning out to vote was 8 per cent lower than their urban counterparts, there has been a complete reversal. Now, 6 per cent more women from villages come out to vote than urban women.

So, who will come to power in 2019? This is a question I could not help but ask the two leading pollsters in the country.

“Anyone who tries to predict an election is either a liar, a fool or a politician,” says Sopariwala. “No one has the foggiest (idea).” Roy adds: “A swing of 3 per cent means 100 seats changing hands. Can you feel a swing of 3 per cent? The job of a journalist is to tell the story and the issues in an election, not to forecast. Leave that to the pollsters.” In India, there are 29 elections being fought, not one, “this is not a ‘national election. It’s a ‘federation-of-states’ election”, they add. “Lok Sabha is becoming less and less important for the voter vis-à-vis state or local elections,” says Roy.

The very next day, the EC announced the dates for the 2019 Lok Sabha elections.

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)