Some have turned to literary narratives of pestilence of one form or another, to make sense of what is happening around us, and referred to the novel by Camus on the plague in the Algerian city of Oran, to the play by Ionesco on the strange disease of humans turning into rhinoceros in a small French village, to the novel by Saramago on a mass epidemic of blindness in an unnamed city with a heavy-handed government, and to the more recent Book of M by Peng Shepherd, where the infected find that they cast no shadow and soon lose their memory, etc. These are all narratives of human frailty and social breakdown, but also of human resilience as in the portrayal of the respective doctors in the novels of Camus and Saramago. (The narratives of Camus and Ionesco have also been interpreted as analogies for the reactions of ordinary people in the creeping Fascism of occupied France).

In this article we shall look at the prospects of social democracy in the post-pandemic world, at the strengthening or weakening of pre-existing tendencies in this respect, and at new elements, circumstances and challenges. Our attempt should be seen as neither a straightforward prediction, nor just a matter of wishful thinking, more a clear-eyed analysis of constraints and opportunities that social democrats are likely to face or have to be prepared for.

Recent cases of decline

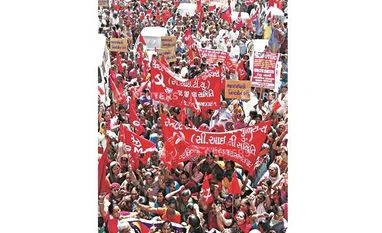

Long before the pandemic, social democratic parties in different parts of the world — Europe, US, Brazil, Turkey, India and so on — have been on a losing streak for quite some time, yielding power or at least a large part of the political space to mostly right-wing populist parties (barring a few cases of left-wing populism in Latin America — even in social democracies there, like Chile, public distrust and protests have been associated with inequality and decline of public services). This has also been a period of the decline of traditional working-class trade unions. With automation and globalisation many traditional jobs have disappeared, and workers have lost much of their faith in the power of trade unions to safeguard their interests. Various business interests run persistent and well-funded campaigns against unions and have captured much of the media and think tanks, succeeding in shrinking organised workers’ traditional rights and domain — from the strike-breaking “right-to-work” movement pushed by employers in the American Rust Belt, to large numbers of “contract labourers” without benefits working side by side with regular workers in factories in India. (In Europe, where the bargaining is not at the individual firm level but at the industry or sectoral level, there is less incentive on the part of business to try to weaken unions at the firm level, but then there is a free-rider problem among individual workers, as they can get the bargained benefits without paying the dues for union membership).

A technological-demographic change has also been at work in shifting the support base of social democratic parties. Let me mention two kinds of change here. One is the way technological change and spread of education and the knowledge-economy had made a significant fraction of the workforce more professional, skilled, or at least white-collar — in work pattern, income profile, lifestyle, assortative mate selection and residence in gentrified parts of cities, they are increasingly different from the older, less educated, often socially more conservative, blue-collar workers who used to be the mainstay of traditional unions. In western countries the former have provided much of the support base for the Blair-Clinton-Obama-Macron-type politics, which has driven away significant numbers of the latter group disillusioned about social democratic parties. The former group’s politics has often connived at some pruning of the welfare state and public services, macroeconomic austerity policies, trade and financial liberalisation, and openness to immigration and to diversity of identity groups (race or gender or sexual preference-based) — all of which have in one way or another alienated many in the latter group of workers.

This technological-demographic divide, more than what Thomas Piketty has mocked as the ‘Brahminical’ attitude of the centrist liberals, is at the root of the fragmentation of the working class support of social democratic parties. The blue-collar workers, resentful of their cultural and economic distance from the more liberal social-democratic workers have turned to populist leaders and demagogues who give voice to their resentment, xenophobia, distrust of experts and majoritarian inclinations to trample upon procedural niceties of liberal democracy like due process or minority rights. In India, Turkey, and Indonesia, such majoritarianism has taken the form of Hindu or Islamic fanaticism and intolerance against their respective Muslim, Kurd or Chinese minorities. The large corruption scandals in the social democratic party regimes in India and Brazil (of Congress Party and PT, respectively) also helped in sealing their fate.

A second change in the composition of the working class has involved the rising numerical importance of service, retail and care-giving workers (added to them now are many of the gig economy workers), compared to the workers in declining or stagnating manufacturing and transportation sectors. On account of locational dispersion of work place, the former are more difficult to organise, and are left out of traditional unions; as a result they now form an underclass of underpaid workers (in spite of the good organisational work done by service worker unions, SEIU in the US and Canada, UNI Europa in Europe). This has reinforced the fragmentation of the labour movement that social democrats used to give leadership to.

In developing countries, the additional reason for labour fragmentation is the large formal-informal divide. A substantial proportion of workers, sometimes the majority (an overwhelming majority in India or Peru), are informal, without any organisation or benefits. Many of these informal workers are self-employed, and more than wage-bargaining issues (which form the staple of union activities), they are more interested in getting credit, insurance, marketing, supply networks, infrastructural facilities, and protection from extortionate police or inspectors, to support their production activities. Social democratic parties have not succeeded in assuring unifying platforms that can build a bridge between the formal and informal workers.

The impact of the pandemic on the constraints and opportunities

Now let us see how the Covid-19 pandemic may or may not have changed some of the factors mentioned above. It is possible that with the pandemic some of the forces of globalisation will get weaker, with people more concerned about dependence on outside sources for some essential products like food, medicines, medical equipment, etc, or in general to supply chains vulnerable to disruption. But this is likely to lead to more diversification of trade outlets, not necessarily less international trade. Some American or European jobs in labour-intensive industries lost to China may now go to Vietnam and other south-east Asian countries. Also, while the general climate of economic insecurity, exacerbated by job and income losses everywhere from the lockdown in the wake of the pandemic, is likely to reinforce the demand for more domestic production and jobs and against specialisation by comparative advantage, it should be clear to many that in today’s world economy of integrated global value chains and continuous swapping of parts, components, and tasks across borders, a large-scale retreat from relatively free trade will be harmful even for domestic jobs in most countries. Of course, trade has to be combined with adequate social insurance for those who may lose out.

Similarly, a retreat from multilateral international institutions is costly for most countries, particularly putting the poorer countries at the mercy of powerful countries in bilateral negotiations. Of course, the multilateral rules disproportionately shaped by corporate lobbies of rich countries do not help workers or social democrats. And the usual stampede of capital from developing countries at the first sign of a crisis makes those countries even more wary of capital-account liberalisation. In any case social democrats should be wary of free international mobility of capital, which in the absence of such mobility for labour reduces the latter’s bargaining power.

But more than from globalisation, labour will get directly hit by labour-replacing automation and digital technology getting a boost as production conditions requiring large numbers of workers to congregate are discouraged, if we have to live with the virus for a long time. So the net effect of these forces may be negative, and the pressure from widespread unemployment and difficulty of mass labour organisation will continue. Another structural factor that will reduce the bargaining power of labour is the pandemic’s likely effect on corporate concentration, with large firms with deep pockets gaining over the small.

As for the composition of the working class, while the remote-working professionals and the digital technology-based knowledge economy will grow in importance, continuing the changing nature of support for the social democratic parties, there may be some revitalising forces generated by renewed efforts to organise the retail and service workers, as there is increased recognition of the importance of the so-called ‘essential’ workers and how underpaid and under-protected they are. In developing countries, where the majority of workers are informal, the increased awareness in the face of economic crisis of their lack of minimum economic security may encourage efforts by labour organisations to find a bridge between formal and informal workers in terms of common demands — like universal health care and some form of universal basic income, which may then form an important agenda and support structure for social democratic parties.

I should, however, point out here that some of the right-wing populist parties (like PiS in Poland or AfD in Germany) are also avid supporters of the welfare state. The right-wing ruling party in India, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), while mocking the Congress party about their welfare (‘dole’) schemes of public food distribution and rural employment guarantee on public works, have not merely continued with these schemes, but have added programmes like provision of subsidised cooking fuel, financial inclusion and housing for the poor, and a minimum income for farmers. In order to differentiate their product, social democrats have to be innovative not just in ‘redistribution’, but also in the sphere of production (or what is sometimes called ‘pre-distribution’) – modifying the corporate organisation, as, for example, in demanding more voice of workers in the governance of the firm, in its decisions to outsource or relocate or to choose the pattern of new technology to be invested in, or in mobilising an active role of labour in the negotiations on international trade agreements or pushing for domestic anti-monopoly legislation.

Inequality and insecurity

Of course, the need for redistribution will be pressing as the pandemic exacerbates the forces of inequality in manifold ways — afflicting the poor more in their dense squalid vulnerable living conditions, the lockdowns destroying their jobs fast, with little social protection (patchy and job-connected in the US, almost non-existent in poor countries) and under-funded and under-equipped public health systems, with collapsed small businesses of the self-employed, with lost skills and low educational background of workers making their labour market adaptability difficult, with the digital divide between workers who can do remote-working and the majority who cannot; and for the long term, more automation encouraged by increased safety risks of labour-intensive production, and the dropouts and large reduction in learning with suspension of in-person teaching in schools and colleges for the young people in poor families. All these forces will have more devastating consequences in poor countries and lagging regions, with scanty fiscal, administrative, and health resources, and for the disadvantaged minorities and women in all countries. Whether the rising inequality and the sheer scale of human suffering will strengthen the redistributive demands of social democratic parties, or, as more often happens, the increasing concentration of economic power in the hands of oligarchs and big firms and the clout they and their lobbies have, can succeed in smothering those redistributive efforts, will of course vary from country to country. It is possible that some of the cash assistance programmes and public health interventions tried out in the crisis may linger.

More than economic inequality, economic insecurity is likely to loom large in the policy environment in many countries in the post-pandemic world – workers usually are less worried about the rising income share of the top one per cent, and more about the precariousness of their own incomes and jobs, and health and pension and social insurance benefits. Social democrats will win more support if they emphasise these areas of their traditional strength, and extend the domain to include the currently unprotected informal sector workers and the new kinds of insecurity like those brought about by pandemics and ecological distress (on the latter, the most immediately pressing may be the insecurity from extreme climate events everywhere and the increasing water scarcity in many developing countries).

Relatively new policies (particularly outside Europe), such as temporary wage subsidies to discourage mass lay-offs, which have been tried out in the current crisis in many countries, both rich and poor, may also be added to the social democrats’ armoury for longer periods. These subsidies should replace the large capital and fuel subsidies in many countries which encourage job-replacing capital-intensive and energy-inefficient methods of production and transportation.

Above all, utmost priority has to be given to a complete overhaul of the public health system, which is broken in countries like India and the US, as became evident in their chaotic handling of their meagre public health resources during the pandemic, whereas not just developed countries like Germany, Australia, New Zealand, South Korea, and Taiwan, but even relatively poor areas with more sturdy public health infrastructure like Vietnam and the Indian state of Kerala performed much better. With the large cuts under austerity policies of recent years, the weakened public health systems in Italy and the UK performed worse.

Premium on a more assertive role of the state

Markets are particularly ill-equipped to handle the risks of pervasive catastrophic events like the pandemic. In general, market fundamentalism is now on the back foot everywhere, there is a premium on resilience over allocational efficiency, and the state is playing a more assertive role. Social democrats may give this a qualified welcome. They may welcome this to the extent the state plays a catalytic role in mobilising an organised response to the crisis, and pays more attention to government procurement capabilities and to public investment in infrastructure, research & development, and other domestic and international public goods (like coordination on global pandemics), and to the extent macroeconomic policy-makers seem now a bit less resistant to the idea of larger fiscal deficits for the sake of relief and stimulus to the economy and to the idea that bailouts of private companies should be conditional on restrictions on corporate payouts to managers and shareholders and on adherence to worker welfare and environmental goals. In general, the issue of adequate state capacity to grapple with emergencies (not just the current coronavirus-related one but future pandemics and other natural or man-made disasters as well) will be of primary concern in most countries. As the cases of success and failure in coping with the current emergency have shown, institutional resilience, agility, preparedness, transparency, and democratic accountability of the state are crucial. Social democrats may also be relieved that in the face of the new virus, distrust of experts and scientific reasoning, shared by populists and post-modern writers alike, has also declined somewhat. The gross mismanagement of the health crisis by populist demagogues (like Trump, Bolsonaro, Johnson, Putin and Modi) who were in denial of the seriousness of the virus or who promised early victory has also been widely noted.

But with the cover of fighting the virus (say, in testing and contact tracing) the surveillance and monitoring power of the state is increasing everywhere; this is a continuation of the disturbing trend towards ‘surveillance capitalism’ sponsored or enabled by Big Tech with ‘big data’ and intrusive software (being taken to an extreme by the digital totalitarianism of China). The elected semi-authoritarian leaders in countries like India, Poland, Hungary, and the Philippines are also using the pandemic opportunity to over-centralise regulations, undermine or hollow out democratic institutions, and to crack down on political opposition and dissent, and in the US and Brazil to roll back environmental regulations. In enforcing the lockdown police excesses and violations of democratic accountability have been quite common. Actually the success stories in fighting the virus have often involved (as in Taiwan and Kerala) considerable decentralised decision-making, information dissemination, and vigorous participation by local officials and communities. Of course, as the current chaotic failure in the US shows, central coordination is necessary particularly in mobilising finance and technical expertise, and allocating scarce medical resources across regions, and in aligning travel restrictions with lockdowns and openings, as the virus surges in different regions at different times.

Conflicting forces at the community level

Community-level social solidarity is a social-democratic asset in fighting the pandemic, and it has been in much display in recent months. But so has been the opposite, as we should keep in mind. ‘Social distancing’ in the shadow of infection and the fear and stigma it has generated can sow suspicion of others in the community (“hell is other people” as a character in Sartre’s play No Exit said), neighbours distrusting neighbours, community vigilantism driving people to hide their symptoms and paradoxically enhancing contagion. In many Indian cities some neighbourhoods have been blocked up and guarded by the residents so that outsiders, particularly poor people, cannot enter; or health workers have been shooed out of their old neighbourhoods for fear of infection; some private hospitals have even refused to admit Covid patients for fear of driving away patients with diseases that are more lucrative to treat. It is possible that such social distrust is more acute in heterogeneous, unequal societies.

One may remember Daniel Defoe writing about London in the plague year 1665:

“Fear and panic could destroy the city as much as plague itself. Many of the doctors fled, along with the rich and powerful; quacks preyed on the poor.... Neighbours informed against each other. People lied to each other – and to themselves.”

This mutual suspicion also applies to the level of the political community called the nation-state. The pandemic has amplified xenophobia, anti-immigration bias and blaming of other countries for spreading the virus — all of which the populist demagogues have made full use of. In some countries the paranoia has involved scapegoating domestic minority communities as super-spreaders (for example, Muslims in India, as in the case of Jews in medieval plague-ridden European cities). Even in the race for development of a vaccine against the virus there are alarming signs of a kind of ‘vaccine nationalism’, foreshadowing a mad scramble as and when the vaccine arrives, and as usual the poorest people and countries are bound to suffer the most in this. Already, the US, along with China, India and Russia, have chosen not to join the Access to Covid-19 Tools Accelerator, launched by the WHO to promote collaboration among countries in the development and distribution of vaccine and treatment.

All this means social-democratic labour and civil society organisations have to give leadership against race-to-the-bottom community and nationalist pursuits; internationally in favour of efforts toward cooperation in issues involving global public goods from which all countries gain (like research on matters of public health or collective attempts to prevent and mitigate climate change, cyber-attacks, international terrorism or organised crime), and to show that even in cases where there are some conflicts of interest among countries (for example, in defining global regulatory standards in labour, finance, trade or tax havens) it is possible to come to flexible compromises in a way that the gains are shared and no country loses.

Cultural struggle

But the struggle is often as much cultural as economic. In general, both on global and local matters, the cultural backlash has often swamped progressive or redistributive measures that you expect the poor to demand. Social democrats have to recapture the local cultural territory appropriated by the populists, and work hard at the grassroots in taming and transcending the parochial nativist passions and prejudices against minorities, immigrants, (and foreigners). One has to persuade people about the benefits of diversity and the contributions to national public welfare by minorities and immigrants, (and the national benefits of an open economy, with appropriate social insurance against its risks).

But one also has to recognise that more open attitudes about poor workers from the ethnic majority communities along with more sensitivity to their social-demographic threat perception may go some way in assuaging the prevailing resentment about many liberal social democrats that they care more for the minorities and immigrants. They can try to relieve some identity-based tension by making their advocacy of economic justice programmes part of a common goal of humanitarian uplift and citizenship, rather than a sectarian agenda of catering to some particular social groups. Balancing the interests of the aggrieved sections of the majority and the chronically oppressed minorities is difficult but doable, if done with some finesse and openness to compromise (unions in the US like SEIU and UNITE HERE have started on this).

One also has to recognise that over the last several years the right-wing populists have captured much of the social media, used it to amplify the general sense of insecurity for which they are the designated saviours, and insulated their followers in closed ideological echo-chambers with such resolute adroitness that it is indeed a formidable task for social democrats to break through the walls of disinformation and conspiracy theories and earn enough general trust and legitimacy in the vicious ‘culture wars’.

On nationalism many have advocated a kind of “civic nationalism,” which combines pride in one’s cultural distinctiveness (and maybe soccer teams) without giving up on some shared universal humanitarian values usually enshrined in liberal constitutions, including tolerance for diversity (as evident sometimes in the composition of those soccer teams). (A popular chant among the mostly white working-class fans of the Liverpool Football Club roaring from the stadium their admiration for the prolific goal-scoring, devoutly Muslim, Egyptian player Mohamed Salah went like this: “if he scores another few/then I’ll be Muslim too!”). In an earlier column on “Coping with Resurgent Nationalism”, I have discussed alternative forms of nationalism, and how in India, arguably the world’s largest multinational society, the earlier social democratic view of civic nationalism based on pluralism and diversity is being challenged by the narrow Hindu-supremacist ruling right-wing party.

Social democrats have sometimes been understandably preoccupied by the historical injustice to some identity groups, alienating in the process many conservative members of the working class who feel left out. In this culture war, social democrats should keep in mind that their strength ultimately lies in finding ways of transcending the divisions of society based on identity. In labour movements, one way of weakening ties to birth-based identities may be to give workers a voice in firm governance, which, as well as even a tiny stake in profit-sharing, can instil a pride in where they work and what they produce. Labour organisations and related social movements, while ensuring social protection, could channel the economic anxiety of workers in the direction of solidarity in local civic engagement, democratic participation and shared human rights, diverting them from the colourful ethnic-nationalist narratives that demagogues use to mobilise this anxiety. They could be sensitive to the genuine communitarian needs and the cultural neglect that workers feel in their relation to cosmopolitan liberal leaders. This may go some way in bridging the gulf between the two groups of workers that we have mentioned before as partly responsible for the erosion of support of social democratic parties among blue-collar workers.

In this article I have discussed how in general the actual or potential strength of social democratic parties may change with the constraints and opportunities of the post-pandemic world. In this I have kept the domain of these parties rather open; even apart from the cases of the self-described social democratic parties, much of what I have said may also apply to some of the left or socialist parties, like those in France, Spain, Greece, Chile or India. Let me end with just two caveats to this broad-brush way of treating the social democratic idea. First, I have ignored the special features (like wage compression, confederate modes of capital-labour bargains, etc) that characterise Nordic social democracy, as somewhat different from most social democratic parties in the world. Secondly, my preference would have been to take the social democratic idea in an analytically deeper sense, beyond the limited modalities of the actually functioning social democratic parties in the world today. To me the idea of social democracy represents a difficult but achievable balance between the conflicting as well as complementary social values of liberty, equality, and fraternity, and between the conflicting as well as complementary social coordination mechanisms of state, market, and the community. I’d like to address in a future column the generic issue of how these balances are shifting in our complex world and difficult time, and how ideological positions of social scientists are coping with them. The writer is professor at Graduate School, University of California, Berkeley

To read the full story, Subscribe Now at just Rs 249 a month

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe To BS Premium

₹249

Renews automatically

₹1699₹1999

Opt for auto renewal and save Rs. 300 Renews automatically

₹1999

What you get on BS Premium?

-

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

-

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

Need More Information - write to us at assist@bsmail.in

)