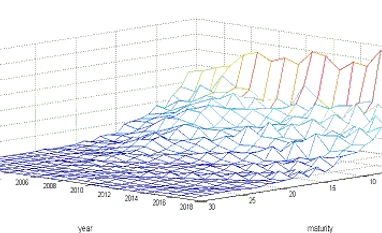

In our recent research, we therefore extend the aggregate debt analysis by undertaking a Hall-Sargent debt decomposition using a novel granular Centre-State security level dataset for India that we have assembled from 2000-2018. The Figure below shows the nominal payouts as a share of GDP by year and maturity just for Centre securities from 2000-2018. Our analysis show that since 2010, there has been a gradual decline in the maturity of the debt raised by the Centre. In 2018, the highest maturity for payouts as a share of GDP is 15 years so that most of the debt that is due is below 15 years.

How did the maturity structure drive the Centre’s debt dynamics between 2000-2018?

Most of the variation in maturity in general debt comes from the variation in the issuance of Central securities. Between 2000-2018 we find that the change in the Centre’s debt-GDP ratio was about 19 per cent. Of this 19 per cent, about 46 per cent was due to the nominal returns on the marketable portion of the Centre’s debt, and about 28 per cent due to the non-marketable portion of the debt. Taken together, the nominal returns on the marketable and non-marketable portion of the Centre’s debt is higher than the other components (inflation, the real growth rate, and primary deficit) between 2000-2018. This reinforces the message from the aggregate debt data that the large contribution of nominal interest payments, especially on marketable debt, continues to pose a challenge to debt management in India.

The other two components that helped reduce the Centre’s debt between 2000-2018 are inflation at about 35 per cent and growth at about 31 per cent. Since India adopted flexible inflation targeting (FIT) de-facto in 2014, the impact of inflation on the debt-GDP ratio is expected to be low in the years following FIT. Indeed, we find that the contribution of inflation falls from 15.6 per cent between 2009-2014 to 6.6 per cent between 2014-2018 on the marketable portion of the Centre’s debt. The primary deficit’s contribution to changes in the debt-GDP ratio falls markedly between 2014-2018 (2 per cent compared to 10.5 per cent between 2009-2014), with the renewed focus after 2014 on meeting FRBM (the Fiscal Responsibility and Budgetary Management Act) guidelines.

How did the maturity structure affect the Centre plus State (general) debt dynamics between 2005-2018?

The table below shows the debt-decomposition results for combined Centre and State securities between 2005-2018 (the security level data for States in our sample starts from 2004). During this period, debt-GDP ratio increased by about 7 per cent and of this 7 per cent, the highest contributing factor was, once again, the nominal returns on the marketable portion of the debt at about 40 per cent. Even the nominal return on the non-marketable portion of the debt was substantial (at about 25 per cent). This is not implausible as during this period, the Centre began to reduce its support in the form of loans to States thereby inducing the States to start borrowing from the market in the form of State Development Loans (SDLs).

During the high inflation years of 2009-2014, the debt-GDP ratio fell by 0.6 per cent. Inflation in this period led to negative real interest rates (-8 per cent) for all three maturity buckets, with the real rates on the 1 year, 2-10 years, and 10+ years being -1.9 per cent, -4.5 per cent, -1.6 per cent, respectively. High inflation during 2009-2014 therefore reduced debt directly, but also via lower negative real interest rates.

In the post 2014 period, with the advent of inflation targeting, growth was high. Despite the helpful contribution from growth in reducing debt, the contribution from the primary deficit (about 8 per cent) and nominal returns (about 22 per cent for all maturity buckets) dominated and this led to an eventual rise in the debt-GDP ratio of about 8 per cent.

Is public debt in India sustainable?

The standard criterion for assessing whether public debt is sustainable is to ask whether, r, the nominal interest rate on public debt, is less than, g, the nominal growth rate of the economy, i.e., debt-GDP is sustainable if r < g, and unsustainable if r > g. We use our granular Centre-State security level dataset to address this question. We use three maturity buckets as in the Table to obtain a weighted average interest rate for public debt over 2005-2018. The advantage of using security level Centre-State data is that the weighted average interest rate is a much better proxy for the “true” interest burden rather than an “effective” interest rate associated with aggregate debt. We find that during this period, the weighted average interest rate, r, where the interest burden is weighted by maturity buckets, continued to be lower than the nominal growth rate, g, apart from a single year in 2015.

This suggests that while public debt in India has been stable in the last 15 years or so, inflation played a quantitatively important role in both liquidating public debt and raising nominal growth, implying a “veil” of sustainability. The security level analysis shows that the large contribution of nominal returns poses a potential risk for unstable debt-GDP dynamics in India so that debt servicing costs need to be carefully watched by policy makers. Thus fiscal imbalances can be a potential challenge for India much like what the global economy is facing today.

Piyali Das is a Visiting Assistant Professor, Economics Area, IIM Indore.

Chetan Ghate is Professor of Economics, Economics and Planning Unit, Indian Statistical Institute – Delhi. He was a member of India’s first Monetary Policy Committee between 2016-2020.

To read the full story, Subscribe Now at just Rs 249 a month

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe To BS Premium

₹249

Renews automatically

₹1699₹1999

Opt for auto renewal and save Rs. 300 Renews automatically

₹1999

What you get on BS Premium?

-

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

-

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

Need More Information - write to us at assist@bsmail.in

)