First, the ban on foreign portfolio investment in corporate bonds with a maturity period of less than three years must be lifted. Until February 2015, foreign portfolio investors were allowed to invest in onshore debt of all maturity, subject only to the restriction that the aggregate foreign portfolio investment in onshore corporate bonds must not exceed $51 billion. However, in February 2015, the RBI prohibited foreign portfolio investors (FPIs) from investing in all onshore debt with a maturity period of less than three years. This was a retrograde move for three reasons.

First, the prohibition is not supported by any economic rationale. Foreign capital flows in rupee-denominated debt flows do not lead to systemic risk. Systemic risk arises from borrowings denominated in foreign currency (as opposed to rupee-denominated foreign borrowings). This is because where an Indian borrower borrows in foreign currency, she bears the exchange risk. If the rupee excessively depreciates, she will have to pay much more than what she borrowed. Unless the Indian borrower hedges such risk or has natural hedges in the form of foreign currency earnings, it may result in disproportionate balance sheet exposures. Where an entire sector relies on unhedged foreign currency borrowings, it can lead to a systemic collapse of the sector as well as financial institutions which are exposed to the sector. This argument does not apply to rupee-denominated borrowings, where the exchange risk is taken by the non-resident.

Rupee-denominated debt, whether between two residents or a resident and non-resident, has the same implications on financial stability. We do not impose any maturity-driven restrictions on the bonds that Indian residents may invest in. The same principle must be applied to FPI investment in rupee-denominated debt.

Second, there is considerable interest among foreign investors in the short-term corporate debt market in India. Data showing the maturity-wise composition of the Indian bond market is not readily available in the public domain. However, the data on debt utilisation status released by depositories show that utilisation of the quantitative debt limit for FPI investment was maximum for commercial papers. For instance, prior to February 2015 when FPI investment in short-term debt was allowed, the utilisation of debt limits for commercial papers was about 95 per cent, while the utilisation of the debt limits for corporate bonds was about 69 per cent. The demand for commercial papers reflects the interest of FPIs in short-term rupee-denominated debt.

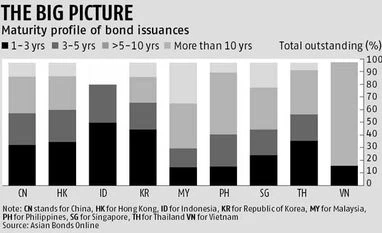

Third, a close look at the maturity profile of bond issuances in similarly placed economies indicates that a substantial proportion of the bond issuances belong to the maturity bracket of one-three years. For example, in Korea, for the quarter ending December 2015, close to 50 per cent of the total outstanding bond issuances belonged to the one-three year maturity bracket. The corresponding figures for Indonesia and Thailand were 57 per cent and 40 per cent respectively (see graph). Pertinently, restrictions on foreign investment based on the maturity profile of local currency denominated bonds do not find precedence in India's peer economies.

This approach makes sense as absolute numerical limits do not reflect the participation in relation to the size of the market. For example, a quantitative limit of $51 billion places an outright ban on foreign participation beyond this limit, irrespective of the size of the market. A percentage-based restriction, on the other hand, is always relative to the size of the market. More importantly, it accords a certain degree of predictability as investors are certain of the intent of the policy-makers. The same thinking must be applied towards FPI investments in corporate bonds. This will encourage deeper engagement of foreigners as the size of the market increases.

The Budget Speech of 2016 has set the agenda for the debt market in India. Extensive structural reforms, such as unifying the regulatory architecture and markets for government and corporate bonds and establishing an independent manager for government debt and financial regulatory reform, have been recommended in the past. Even as we procrastinate on these reforms, policymakers must begin to reverse some of the immediate damage.

The writers are with the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy

)