Of course, we too have a robust and vigilant culture of constitutional review by the higher judiciary where executive actions are challenged. Not too long ago, the Supreme Court struck down Section 66A of the Information Technology Act, which it found would curb free speech.

The state gets away with a lot — particularly in “heavy matters” where terms such as “national security”, “interests of investors”, “public interest”, “integrity of securities markets” can be invoked, and a law officer representing the government is willing to raise the decibel level about tragic outcomes if the judiciary were to stop a decision by the government. Eventually, the courts may rule on the constitutional validity of a law (it is tougher if the law has been in play for a while, as compared with a newly introduced amendment) and hold that the law is unconstitutional. Likewise, without granting any temporary restraint, courts could eventually hold an executive decision to be unconstitutional. At times, this could lead to a situation of “operation successful; patient dead” (for example, Maneka Gandhi’s challenge to her passport being taken away).

Judge James Robart, the US District judge who stayed nationwide the enforcement of Trump’s executive order (incidentally, carrying a grandiose title: “Protecting the Nation from Foreign Terrorist Entry into the United States”), says it well in his concluding paragraph. The entire portion is worthy of being reproduced:

“Fundamental to the work of this court is a vigilant recognition that it is but one of the three equal branches of our federal government. The work of the court is not to create policy or judge the wisdom of any particular policy… That is the work of the legislative and executive branches and of the citizens of this country who ultimately exercise democratic control over these branches. The work of the judiciary, and this court, is limited to ensuring that the actions taken by the other two branches comport with our country’s laws, and more importantly, our Constitution. The narrow question the court is asked to consider today is whether it is appropriate to enter a TRO (temporary restraining order) against certain actions taken by the executive in the context of this specific lawsuit. Although the question is narrow, the court is mindful of the considerable impact its order may have on the parties before it, the executive branch of our government, and the country’s citizens and residents. The court concludes that the circumstances brought before it today are such that it must intervene to fulfil its constitutional role in our tripart government.”

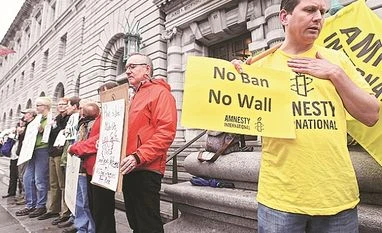

The states of Washington and Minnesota had challenged Trump’s order. Trump had won an election on the promise of bringing in such restrictions on the entry of Muslims and also refugees. But if that popular measure is not in line with the Constitution, the court would intervene. Perhaps, another judge may have had a different view. Indeed, one could argue that there are as many courts as there are benches of the court. So far, none has in the USA.

Shift to India. The law enabling the creation of the Aadhaar system was pushed through by labelling it a money bill to avoid a discussion on the floor of the Rajya Sabha. The Speaker of the Lok Sabha has certified it to be a money bill (the Rajya Sabha has next to no say in draft laws that are money bills). A constitutional challenge is pending in the Supreme Court and one of the issues to be considered is whether the “final” nature of a Speaker’s certification can at all be questioned. We will all know eventually, many years down the line, but Aadhaar would become a way of life by then.

Same is the story with demonetisation. Courts were indeed approached the morning after the government declared 85 per cent of the currency in circulation to be illegal — quite similar to an abrupt and arbitrary stoppage of people from select countries entering the US regardless of whether they were US residents. No court intervened with a stay order. If the executive branch were to say that the move is aimed at fighting terrorists using counterfeit money, there is not much left to expect. We would end up eventually with guidelines on how the government and the Reserve Bank of India must conduct themselves. And when that happens, courts would in fact be dispensing wisdom on executive action — exactly what Judge Robart warns against.

To read the full story, Subscribe Now at just Rs 249 a month

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe To BS Premium

₹249

Renews automatically

₹1699₹1999

Opt for auto renewal and save Rs. 300 Renews automatically

₹1999

What you get on BS Premium?

-

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

-

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

Need More Information - write to us at assist@bsmail.in

)