Under the WTO Agreement on Agriculture (AoA), domestic agri-subsidies are classified into three categories; green, blue and amber. Under WTO principles, "amber box" subsidies create trade distortions because they encourage excessive production through farm subsidies to fertilisers, seeds, electricity and irrigation. Within the amber box, de minimis is the minimal amount of subsidy WTO permits at 1986-88 prices. The de minimis figures for developed and developing countries are at five and 10 per cent of their agricultural production respectively. At the 2013 Bali Summit India, led by the United Progressive Alliance government, had agreed to sign the TFA under a "peace clause" that gave developing countries exemption from the 10 per cent de minimis provision until 2017.

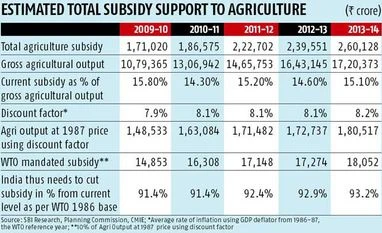

India, however, has legitimate and pertinent concerns regarding the WTO obsession with the 10 per cent upper limit for domestic agri-subsidies. Let us consider the case for rice. The WTO has fixed an external reference price (ERP) for rice at Rs 3.52 per kg (at base 1986-88 prices). Interestingly, ERP being a non-inflation and dollar-denominated adjusted proxy for the cost of production has, thus, been unchanged since the base year. But the cost of production in the domestic economy has escalated in the last decade by more than five times. More specifically, food product prices have grown by a similar amount. At the same time, the Indian rupee has depreciated almost four times from 12.78 per dollar in 1986-87 to 60.50 per dollar in 2013-14. Given such a huge variation in price and currency value, India's argument for base year correction is logical and justified.

To compensate for increased production costs, the Government of India procures rice at a minimum support price (MSP). Currently, MSP for rice is Rs 13.60 per kg, whereas the cost of production is Rs 19.35 per kg, implying that even rapid increases in MSP have failed to compensate the Indian farmers from the vagaries of market forces in the last two decades. Further, the fact that domestic prices (Rs 27.42 per kg) are almost on a par with international prices (Rs 28.62 per kg) takes the substance out of the oft-repeated argument that India will dump its cheap agro-products in the international market.

We believe the WTO should link this amber box quota to population instead of production. Additionally, developed countries have moved their trade-distorting measures from the amber box to the green box because the latter is protected from legal challenges at the WTO. A simple fact based on WTO reveals that most of the subsidies given by these developed countries are listed under the green box. The EU, for instance, has slashed its amber box subsidies from euro 50 billion in 1995 to euro 8.7 billion in 2009, while its green box subsidies have shot up from euro 18.7 billion in 1995 to a whopping euro 83 billion in 2012, accounting for 19 per cent of total farm revenues. As for the US, its green box payouts have increased from $46 billion in 1995 to $120.5 billion in 2010. A huge component of these payouts is for its domestic aid programme, which has soared to almost $95 billion.

The United Nations' Millennium Development Goals to eradicate extreme poverty and hunger stands on the foundation of the food security legislation. For most of the developing countries, including India, public stockholding for food security is a livelihood issue. The TFA is based on the agenda of maximum reduction in trade barriers and red-tapism to promote global trade. India should definitely be a signatory to TFA, but must safeguard its interest. As the experience of developed countries show, there is no shame in doing so.

The writer is Chief Economic Advisor, State Bank of India. These views are personal. Bibekananda Panda, economist, contributed to this article

)