On February 1, 2018, the Union Budget raised Customs duty on as many as 46 items in a bid to “provide adequate protection to the domestic industry”. This was the fifth and last full Budget of the Narendra Modi government in its first term. But that was not the first time the Modi government betrayed its protectionist tendencies.

In the earlier four Budgets, presented by then finance minister Arun Jaitley, Customs duty was raised, but on only a few items. In the first three Budgets, the reasons cited for the duty increases ranged between “boosting domestic production” and “incentivising domestic value addition” along with promoting “Make in India”. The fourth Budget was a little more upfront by saying that the duty increase was necessary to “provide adequate protection to the domestic industry”.

What made the fifth Budget in February 2018 a watershed in terms of the Modi government’s love for protectionism was the huge increase in the number of items whose Customs duty was raised with immediate effect. That this happened just about a year before the general elections and that the subsequent Budgets of 2019 and 2020 have maintained the policy of raising tariffs are no less significant.

The logic or economic illogicality of raising Customs duty on a host of items in the name of protecting the domestic industry stems from the politics of nurturing domestic corporate and trade lobbies. The Bombay Club of the 1990s had lost its battle against the Narasimha Rao-Manmohan Singh duo’s tariff reduction policy, but it has bounced back with greater energy now, thanks largely to the political support it gets from the current ruling dispensation.

But how effective was the policy of increasing tariffs in 2018? Two years is a reasonably long period to assess the impact of any such tariff increases. Import data for 2018-19 and 2019-20 are available and it would be instructive to see the impact those tariff measures of 2018 had on imports in the following two years.

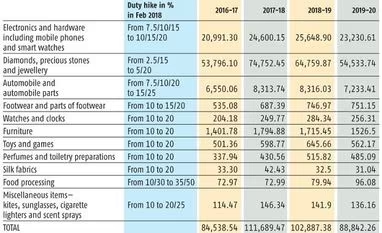

Remember that the 46 items, whose Customs duty was raised from February 2018, accounted for 22-23 per cent of India’s total imports in 2015-16 and 2016-17, the period immediately before 2018-19 when the higher duty was levied. The trajectory of imports of these 46 items was also significant. In 2016-17, their imports at $84 billion was a little less than the $88 billion of imports in 2015-16.

So, why were these items chosen for the levy of higher import tariffs? Of course, the April-January 2017-18 period had showed a spike in their imports to about $94 billion and this could have triggered the action for higher import duties. For the full year of 2017-18, imports of these 46 items had risen to $112 billion.

But this surge in imports was largely in keeping with the overall increase in imports that year. India’s total imports in 2017-18 rose by 21 per cent to $465 billion. This increase was also facilitated by an appreciation of the Indian rupee against the US dollar. The rupee’s average exchange rate for the US dollar in 2017-18 appreciated by about 4 per cent to Rs 64, compared to Rs 67 a year ago.

The troubling question is why the government did not rely on a more realistic and market-driven exchange rate management mechanism by allowing the rupee’s depreciation and, thereby, checking a rise in India’s imports. It should have been clear to the policymakers that a 4 per cent appreciation in the rupee’s value in one year was one of the key factors responsible for a surge in imports. Instead, the government opted for a discretionary regime by increasing the Customs duty on over 46 items, thereby picking winners and losers in the name of protecting the domestic industry.

Quite ironically, the Indian rupee depreciated sharply by 8.5 per cent in 2018-19. The following year also saw another depreciation of 1.4 per cent. Thus, in the two years after the Customs duty hike in February 2018, the rupee depreciated by about 10 per cent. The promised protection to the domestic industry, by raising tariffs on those 46 items, became more than adequate. In addition to the depreciation burden of 10 per cent, the tariff increase ranged between 5 and 10 percentage points for most items. While the increase for food processing items was higher at 20 to 40 percentage points, the duty on diamonds and precious stones had been doubled to 5 per cent.

In spite of that, however, imports of these 46 items have not seen any collapse in the two years since the increase in the Customs duty. Quite to the contrary, imports of footwear, watches and clocks, food processing items (mainly fruit juice) and perfumes & toiletry preparations have increased in the last two years over what these were in 2017-18. The impact of the tariff hike on electronics and hardware (mobile phones and smart watches included), automobile and automobile parts, diamonds, precious stones and jewellery, furniture, toys and games, silk fabrics and miscellaneous items like kites, sunglasses, cigarette lighters and scent sprays has been quite small.

It is possible to argue that the impact of the duty hike on imports would be seen over a longer period of time and the trend in the last two years is not a reliable indicator. But the larger question is whether domestic manufacturers have been offering indigenous substitutes for the items, whose imports have now become costlier. Or whether imports are continuing to take place, though at a slower pace, but with the added cost of imports being passed on to the consumer, making Indian manufacturing even more uncompetitive in terms of costs and efficiency.

That the government continues to rely on the flawed policy of raising tariffs in the name of providing protection to the domestic industry is evident from the two Budgets that were presented in the last two years. In July 2019 and again in February 2020, import duties were raised on 37 and 16 more items, respectively, in order to “provide a level playing field to domestic producers” and to promote Make in India. The duty on some items such as footwear and toys was further raised, indicating that the February 2018 duty hikes were not adequate to provide protection to the domestic industry.

Discretion, it seems, will continue to rule India’s tariff regime, irrespective of whether these lead to a significant curtailment in imports in the short run. And whether they can lead to an increase in domestic manufacturing capacity to substitute imports of such items, only time will tell. But there can be no dispute over the adverse impact such a policy will surely have on India’s manufacturing competitiveness.

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)