The headline inflation is currently benign and various measures of core inflation suggest that there has been an underlying disinflation since Q2 2016. Credit growth is the lowest in decades and balance sheets are strained. Against this backdrop, the Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI) decision to change its policy stance to “neutral” from “accommodative” in February and the relatively hawkish April minutes might seem at odds with reality.

However, when seen through the prism of the four per cent inflation target, it is a rational move.

The central question is whether low inflation will persist. Our analysis suggests that the current benign inflation readings are caused by transitory factors, which will reverse, and cyclical factors, which will gradually fade. Moreover, a few impending one-off factors warrant caution, given the still-elevated inflation expectations.

Transitory factors

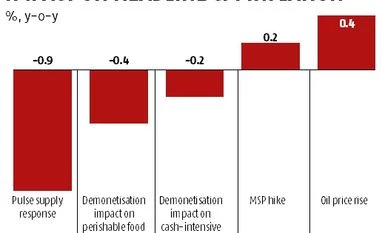

Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation has moderated from 5.7 per cent in Q2 2016 to 3.6 per cent in Q1 2017. Of this, we estimate that demonetisation alone has lowered headline inflation by Rs 60 bp, as the cash shortage spurred distress selling of perishable food, particularly, vegetables by farmers, and damped demand for cash-intensive purchases, which account for around half of the core CPI basket.

Another 90-bp drop in inflation came from pulses deflation, whose production surged to 22 million tonnes in FY17, the highest in 67 years. Several factors such as higher market prices in previous years, bonuses to top up minimum support price hikes and a good monsoon led to a bumper supply.

In April 2017, the deflation in vegetables and pulses intensified further. However, vegetables and pulses cannot remain in perpetual deflation as that would only disincentivise future supply response, triggering a shortage in the following year. Additionally, the disinflation triggered by demonetisation — in perishables as well as in the cash-intensive core categories — should reverse with the ongoing remonetisation. Disinflation in the latter has already started to stabilise somewhat.

The cyclical factors pulling down inflation are likely to gradually fade.

1) Nominal rural agricultural wages have the highest correlation (Rs 0.9) with CPI inflation. They accelerated to 8.1 per cent year-on-year in March from five to six per cent for most of 2015-16, likely due to a 42 per cent increase in basic minimum wages, but this rise could persist given the push towards rural road construction.

2) Minimum support prices (MSP), which were a key driver of the disinflation during 2014-16, are unlikely to fall any further in 2017 given monsoon risks and farmer distress caused by current low market prices.

3) The output gap widened after demonetisation and is currently negative (minus one percentage point in Q4 2016, on our estimate). However, the lagged effects of easier financial conditions, impending pay hikes for state government employees and improving global demand suggest that a cyclical recovery lies ahead, which should gradually narrow the output gap. We estimate that together, these cyclical factors could add Rs 50 bp to headline CPI.

The one-offs

A potentially mild but inflationary impact of the goods and services tax (GST) and the impending house rent allowance increases under the Seventh Pay Commission are a couple of the one-offs to be considered. The latter is purely statistical, but higher headline inflation could influence expectations, which warrants caution.

At the same time, we would highlight that government reforms are moving in the direction of structurally lowering inflation. Initiatives such as the e-National Agriculture Market, elimination of cascading of taxes and greater efficiency after GST, lower logistics cost due to investment in transport infrastructure are all steps in the right direction. However, they will take at least two to three years to sustainably lower inflation.

One way to gauge whether the inflation decline is structural is to look at price pressures in non-discretionary items, as these are cyclically insensitive and are unlikely to have been impacted by demonetisation. Inflation in categories such as health services (hospital charges, doctors’ fees, X-ray charges and medicine) have also trended lower over the past year. However, their contribution to lowering headline inflation is Rs 20 bp, which is still small compared with the role played by transitory and cyclical factors in lowering headline inflation.

Until there is a clearer sign of a structural decline, it is indeed prudent for the RBI to remain cautious and ensure that the reversal of transitory factors, the fading of cyclical factors and the rise in headline inflation due to one-off factors do not un-anchor inflationary expectations, as the latter are among the key factors (along with supply-side reforms) in lowering inflation on a sustained basis.

Varma is chief India economist, Saraf is India economist at Nomura

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)