A week after Majid Khan shocked his friends and family by joining the Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT), he walked into an army camp to surrender. The return of the young son was due to emotional appeals by his mother, combined with reassurances by the army and police that Majid would face no harassment and would also be assisted with his rehabilitation.

Why has this single case attracted so much attention? The return of even one person from terrorist ranks dilutes the narrative that the youth of Kashmir are keen to pick up the gun against the state. Spurred by Majid's surrender, more families of local terrorists have taken to the social media asking them to return home.

There is obvious worry among the terrorist organisations; LeT gave a statement that they had permitted Majid to return on the request of his mother. A few days later, Riyaz Naikoo, a Hizbul Mujahideen commander, released an audio clip stating that families are “being pressurised to make appeals to their sons to return home”. In his desperation, and sounding like Zakir Musa of the al Qaeda, Riyaz turned to religion, saying, “If we don't sacrifice for Islam...If for the sake of Islam we can't stay away from our families, then who will fight for Islam?”

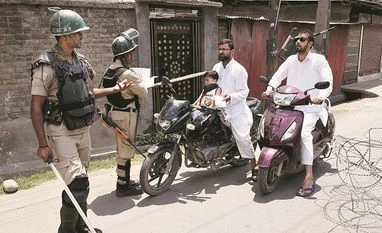

This is an opportunity for the government to get local terrorists back into the mainstream, and it should not be missed. One of the main reasons for the situation worsening in 2015 and 2016 was the increase in young men joining terrorist ranks. This in turn led to locals interfering in army operations in an attempt to save their own kin from certain death.

Poorly trained, the life of a local terrorist was in months, for some only a few days. Although unable to make any impact when alive, their funerals attracted thousands of mourners, stirring frustration and anger. It was our assessment at that time that youth joining terror organisations were mostly friends and relatives of those who had been killed. This led to a cycle of more numbers killed, but greater terrorist recruitment.

The return of the misguided youth will be a key component of the counter-terror strategy in Kashmir. It can be a body blow to terrorist ideology and Pakistan's narrative that the Kashmir conflict is mainly indigenous in character. However, a successful implementation of this strategy will require more than simply appeals and promises.

The state needs a new 'surrender and rehabilitation policy'. In preparing this policy, focus must be on rehabilitation. The current policy, framed in 2004, is appropriately titled 'Rehabilitation Policy' but is mostly concerned with the financial incentives provided on surrender. Rehabilitation merits one line, “For a surrenderee who desires to undergo any vocational training for self-employment, the Government will facilitate such training free of cost at the centres to be decided on case to case basis.”

For proper reintegration into society, rehabilitation is the key. The government's record in this area has been poor. Since 2010, a number of terrorists who had left Jammu and Kashmir for Pakistan Occupied Kashmir (POK) in the early years of insurgency have returned via Nepal with their wives and children. This route was given a somewhat unofficial sanction but there have been no attempts to rehabilitate this group. Considered foreign nationals, even the children find it extremely difficult to get admission in schools. Rules and procedures are often quoted but they cannot compensate for the sense of injustice.

Surrendered terrorists who have not been adequately integrated into the society remain vulnerable to security forces and terror organisations, both looking to exploit them. Even if a few of them retake to the gun, as has happened in Kashmir, it becomes a reason for critics to recommend that surrenders should be discouraged. In the past, such thinking has restricted us in taking comprehensive steps to getting dissatisfied terrorists back into the mainstream.

Properly rehabilitated surrendered terrorists are a real force multiplier for the government to show that recourse to violence is futile, and discourage recruitment. Some of them could be included as essential members of a comprehensive counter-radicalisation strategy. The Quilliam Foundation was established at London in 2007 by Ed Husain, Maajid Nawaz and Rashad Zaman Ali, three former members of the Islamist group Hizb ut-Tahrir. It is doing excellent work in the field of counter-extremism.

After the 2005 earthquake devastated POK, a very large number of Kashmiris who had crossed over in the 90s expressed a desire to return, being disillusioned by their poor treatment at the hands of the Pakistan Army and ISI. As they came and started surrendering at the Line of Control, we imagined the worst. Fears were expressed that these people were being sent by the ISI to stoke up trouble in J&K. These fears translated into an unrealistic policy of 2010 which mandated that surrenders from POK would not be accepted at the Line of Control but at the official entry points between India and Pakistan; the Delhi airport, Wagah, Kaman and Chaka-da-bagh. To my knowledge, not one person has surrendered at these points.

We have missed many opportunities in the past but there is a window today. The state government, army and the police have clearly expressed the need for a new rehabilitation policy. The Centre must not wait too long in the implementation, lest Majid’s story be forgotten. D S Hooda retired from the Indian army as General Officer Commanding-in-Chief of the Northern Command

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)