A week after Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced the decision to scrap old Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 currency notes, business in the agricultural market of Pathardi, 350 km east of Mumbai, fell by 60 per cent, indicating how the rural economy of India’s richest state, Maharashtra, recovering from two years of drought, is slowing.

Pathardi’s Agriculture Produce Market Committee (APMC), representative of 2,500 such markets in India, is where most agricultural trade in the region takes place – almost all of it in cash. A slowdown in these markets can have wide-ranging effects on farmers, traders and the Indian agricultural economy.

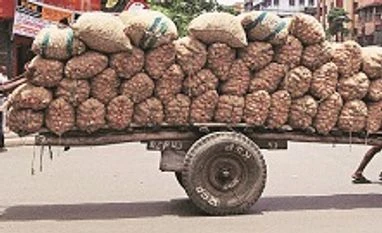

The arrival of vehicles loaded with agricultural produce entering the Pathardi market fell by 75 per cent, the arrival of cotton dropped by 80 per cent, and the sale of cattle fell by 50 per cent in comparison to the week before the ban of notes, show data gathered by IndiaSpend from market officials.

Pathardi: How business fared after note ban

Also Read

Bhimsen Mahadev Ghuge, a 50-year-old cotton farmer, lost 15 per cent on a cotton transaction. He did not want the money in old notes, so he sold his produce to an unregistered trader outside the APMC market gate for Rs 4,200 a quintal, lower than the market rate of Rs 5,000 a quintal.

“I have to manage my family expenses and pay the wages of labourers who work in my farm in Rs 100 notes,” Ghuge said. “I have incurred a huge loss this season.”

Traders at the Pathardi market were willing to pay for produce and cattle in old notes or, new notes of Rs 2,000. But, farmers, whose daily expenses are much lower, are unwilling to take Rs 2,000 notes, unsure of whether they would be able to change it for more usable notes of smaller denominations.

)