Long ago, in 1978, the political supremacy of the Maratha community in Maharashtra was disturbed by Sharad Pawar. A Maratha by caste but non-conformist, Pawar, then 38-year-old and the youngest chief minister of the state, drew the ire of the Maratha élite.

Two decades later, the first Brahmin chief minister of the state, Manohar Joshi, had to step down a few months before a fresh Assembly election owing to multiple reasons, caste being one of them, to make way for Narayan Rane, a Maratha leader from coastal Konkan.

Come 2018, with Maharashtra’s second Brahmin CM, Devendra Fadnavis, at the helm, caste has not just taken centre stage in the state politics, but its repercussions have reached the psychological depths of society at large.

The Maratha agitation, primarily for reservation in education and government jobs, characterised by silent marches in cities and towns till recently, started in September 2016 and the 58th silent rally culminated in Mumbai on August 9 last year.

Exactly a year later, last week, the agitation turned violent with public properties being damaged. Demonstrators have been arrested in some cases in Mumbai, Pune, Osmanabad and other towns in the Marathwada region. According to reports, around 18 Maratha youngsters have committed suicide in the last few months as part of the ongoing protest.

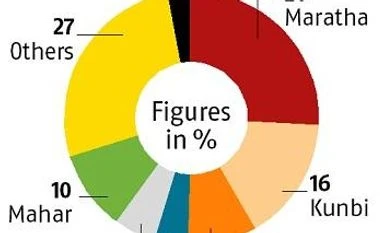

The Marathas are the dominant agrarian community in Maharashtra and they form about 30 per cent of the state’s population. The agitating Maratha youth is demanding reservations in general; on the anvil is a recruitment drive for 72,000 government jobs.

Looking back at the pre-Mandal regime, it was the governor (the cabinet de facto) who decided the castes to be added to the list of ‘other backward classes’. Union and state-level backward class panels were mandated after the Indra Sawhney judgment in 1992, but Maharashtra granted legislative status to the commission only in 2005.

Besides these delays that reflected an inclination to act slowly, the panels formed after 2005 were poor in data collection and interpretation. Further, these reports were not tabled in the state legislative assembly, say lawyers who have been privy to these matters.

The Bombay High Court rejected the suggestions of the Narayan Rane committee, hurriedly set up by the outgoing Congress-led government to study the issue of Maratha reservation. It did secondary research on data pertaining to 1.8 million people in less than two weeks.

“Neither the Congress-Nationalist Congress Party (NCP) government nor the BJP government has articulated the community’s demands properly in the commissions and courts, leaving us with the only option — hitting the streets,” said a protester from Pune.

The vaults of power

According to a study done by Abhay Datar and Vivek Ghotale of Savitribai Phule Pune University on the social and regional profiles of cabinet ministers of Maharashtra, the share of Maratha leaders in the state cabinet reduced from 62 per cent in 1999-2004 to 44 per cent in the current cabinet.

Owing to a better representation to upper and upwardly mobile communities, non-Congress governments in the state reflect a socially balanced ministerial profile. The forward castes' representation in the Manohar Joshi cabinet (1995–1999) was more than that of the Marathas.

On the other hand, the three successive Congress-NCP coalition governments from 1999 to 2014, and the period before the Emergency, when Indira Gandhi was largely unchallenged, had the highest number of Maratha ministers in the state cabinet.

Backwardness?

The Pune-based Gokhale Institute of Politics and Economics carried out a study— on directions from the government — to assess the backwardness of the Maratha community using proxies such as the proportion of its members in casual labour and more importantly in farmer suicides. It found 26 per cent farmers who committed suicide were Marathas, the highest for any caste group. However, it found unavailability of irrigation was a stronger reason for suicides. About 84 per cent farmers in Marathwada and 90 per cent farmers in Vidarbha who ended their lives were tilling un-irrigated land.

In comparison to labourers belonging to reserved castes, the Maratha workers are more educated and access financial services like loans more, it showed.

Dwindling political impact

Contrary to the belief that the Maratha community prefers the NCP and the Congress, political scientist Suhas Palshikar, in a 2014 study based on data from the Centre for Study of Developing Societies, demonstrated that a larger share of Maratha votes went to the Shiv Sena and the BJP in 2014. This could the reason for the Congress and the NCP showing solidarity with the community.

Maharashtra Pradesh Congress Committee Chief Ashok Chavan and former CM Prithviraj Chavan publicly called for mass resignations, owing to the government’s alleged inaction, but the Congress’s central leadership rejected the proposal, sources said.

Vinayak Mete, a Maratha leader in the government who runs an organisation, Shivsangram, and is the chairman of the Shivaji Memorial Committee, has been working towards the cause of reservation for three decades. He said that steps had been taken in the form of government financial support to Maratha and OBC entrepreneurs, scholarships and hostel services to students. But he admits the implementation has been lax to some extent. “The Opposition alignment is nothing but a move made with an eye on the upcoming elections,” he said.

All eyes, however, are on an upcoming report from the Maharashtra State Backward Classes Commission. The report, which will be an extensive survey of the Marathas in the state, is due on November 15.

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)