Nagaland Governor R N Ravi must feel bitter. The former deputy national security advisor spent five years (2015-20) talking to militant groups in Nagaland to get them to agree on the Framework Accord between the National Socialist Council of Nagaland Isaak-Muivah (NSCN IM) and the government of India. But he could end up as nothing more than a mention in a file in the ministry of home affairs like those before him: Y D Gundevia, foreign secretary (1965), L P Singh (ICS, former home secretary, 1975), K Padmanabhaiah (former home secretary 1990s), R S Pandey (former Nagaland chief secretary and chief negotiator to talks with Naga rebel groups who chucked it up, joined the BJP, and is currently MLA from Bagaha in Bihar); and many others in between.

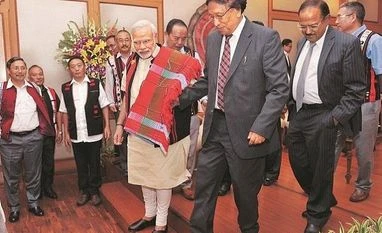

In 2015, Prime Minister Narendra Modi and NSCN IM supremo Thuingaleng Muivah signed a Framework Agreement to address Naga identity and sovereignty issues, and end the oldest insurgency in India. Details of the agreement were not made public even to Parliament.

Today, after talking for five years, the NSCN IM says it doesn’t want Ravi as the interlocutor anymore because he trashed their reputation by calling them extortionists and thugs. Ravi, on his part, has issued an order asking state government employees to issue declarations that none of their relatives has any dealings with militant groups – especially the NSCN IM. The trust deficit is wide and deep. And it is the NSCN IM which is having the last laugh as speculation grows that Ravi may have been replaced as Naga interlocutor.

How did it come to this?

On August 17, 2019, Ravi disclosed the prime minister has asked him to conclude talks on the Framework Agreement in three months. “In the last five years, we have resolved all the substantive issues,” he said, “comfortably”. But behind the relaxed air, there was anxiety: The PM was getting restive, had set a deadline, and Ravi was under pressure to get the NSCN IM to sign on the dotted line. He thought the matter was all but settled: After all, under the deal, hadn’t the NSCN IM, speaking for the Naga people, agreed to give up the idea of Naga sovereignty and settle for a settlement “within the Indian federation”.

But it was much more complex. The government scrapped the special status to Jammu & Kashmir, granted via Article 370, on August 5, 2019. This caused unease in the Northeast, which enjoys extensive protection of its identity via Article 371 (A-H). Home Minister Amit Shah’s reassurances in Parliament the Northeast could not and would not be equated with Jammu & Kashmir cut no ice. The NSCN IM began mulling anew the implications of just what it had signed on. Jammu & Kashmir had lost exactly what the group were asking for: Its own flag and constitution.

Ravi had his own compulsions. He had to produce an agreement by October 2019. But that was possible only if he could create conditions to pressure the NSCN IM to the point where it would have no option but to sign it. So he proceeded to use the oldest trick in the book: He got together groups that are rivals of the NSCN IM, banded together as the National Naga Political Groups (NNPG), and got them to endorse and agree to sign the agreement (which, in the first instance had been with the NSCN IM, treating them as the sole representative of the Naga people), expecting the fear of being isolated would force the NSCN IM to come to the negotiating table.

But the NSCN IM has not been India’s oldest insurgency for anything. It could see that the government of India was trying to undermine the group, so gradually it too began ratcheting up the pressure.

In an interview to North East Live in February 2019, Muivah said: “Old issues are not resolved — only one government, integration of all Naga contiguous areas (Nagalim), our flag, our constitution…this is our stated stand.” Ravi retorted: ‘This is not what was offered’.

On 28 February, 2020, according to South Asia Terrorism Portal, in an interview, Ravi said: “Delay in concluding talks is entirely on the part of the NSCN IM. It seems not prepared for a settlement and is using delaying tactics by giving new mischievous interpretations on the already agreed provisions of contentious issues. Pan-Naga entity was mutually agreed on to be a cultural body with no political role or executive authority. After October 31, it wants the pan-Naga body to have political and executive influence over the Nagaland government”.

Recently, the NSCN IM issued a document titled “Mr R N Ravi’s misdoings as interlocutor”, which said the governor has been under the “NSCN’s scanner” from the time he “twisted the Framework Agreement and misled the Parliamentary Standing Committee on the steps taken to solve the Naga issue”. The group referred to a report furnished by Ravi to the Parliamentary Standing Committee that said the agreement talked of a solution “within India” and not “with India”. It pointed out Ravi’s letter to the Nagaland government in June referred to the rebel bodies as “armed groups”, accused them of extortion, and charged their “parallel governments” were in contravention to India’s security.

The NSCN IM made it clear it was deeply offended. It said publicly it didn’t want to Ravi to be the interlocutor any more. The government might have decided not to throw good money after bad. So, Ravi was missing from the recent meeting between the NSCN IM and New Delhi.

In terms of optics, the NSCN IM demanded and got what it wanted: Replacement of the interlocutor and a demonstration of strength to other rivals. The next move is Ravi’s. This is a crucial and sensitive time: If despite dwindling public support, the NSCN IM elects to go back to the jungles and the guns start booming again, it can be back to the drawing board.

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)