Is beauty a "bad" word in the age of cutting-edge, anxiety-ridden art? This is one of the questions that 10 contemporary artists from India and Pakistan have come together to answer.

That they are all working with the miniature art tradition and come from different countries and belong to different generations makes this exhibition a multi-layered discussion.

The first question that rises is: how artists from a single tradition, but with divergent influences, take forward a 600-year-old practice like miniature art? And, what are the different ways in which they interpret it? The second layer is about current politics and its role in a tradition that was founded by Mughal emperors to eulogise their bravery. And the third question is, of course, about the role of beauty today.

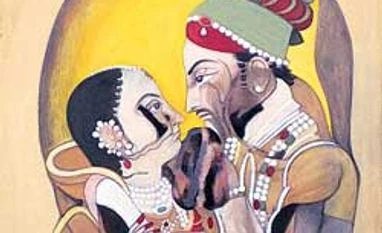

Some artworks, with their surface prettiness, lend themselves more easily to this last question. Manisha Gera Baswani's works draw from Nainsukh's crystal mountains and talk about inner strength. Desmond Lozaro's gold takhtis on an indigo background invoke Mir Sayyid Ali's painting of a scholar as well as every child's writing board. Manjunath Kamath's miniatures and mandala-inspired fragments invoke Persian and Buddhist art. Wardha Shabbir's works hark back to Persian miniatures with floating trees, flying animals and djinns, but the canvases also have carnivores and cawing rooks. And, V Ramesh's "Body/Offering" are almost photographic in their representation of objects like an empty chair and a lit lamp.

Ghulam Mohd Sheikh and Nilima Sheikh's works focus on Kashmir. Ghulam's "Thinking Beauty in the Times of Terror" teems with dark colours and floating figures, from stone pelting youngsters to saints like St Francis Assisi feeding birds. Nilima's works draw on Indian, Chinese, pre-Renaissance and Persian influences and their delicate strokes show grieving mothers and desolate towns of Kashmir. Her works, writes art historian B N Goswamy in the catalogue, touch on the pain of Kashmir, "that wound eternally touched up and iodised, but never healed".

That they are all working with the miniature art tradition and come from different countries and belong to different generations makes this exhibition a multi-layered discussion.

The first question that rises is: how artists from a single tradition, but with divergent influences, take forward a 600-year-old practice like miniature art? And, what are the different ways in which they interpret it? The second layer is about current politics and its role in a tradition that was founded by Mughal emperors to eulogise their bravery. And the third question is, of course, about the role of beauty today.

Zahra Hassan’s ‘Annihilation VI

Ghulam Mohd Sheikh and Nilima Sheikh's works focus on Kashmir. Ghulam's "Thinking Beauty in the Times of Terror" teems with dark colours and floating figures, from stone pelting youngsters to saints like St Francis Assisi feeding birds. Nilima's works draw on Indian, Chinese, pre-Renaissance and Persian influences and their delicate strokes show grieving mothers and desolate towns of Kashmir. Her works, writes art historian B N Goswamy in the catalogue, touch on the pain of Kashmir, "that wound eternally touched up and iodised, but never healed".

Wardha Shabbir’s ‘One World Here Another There

"Revisiting Beauty" can be viewed at Gallery Threshold, New Delhi, till September 30

More From This Section

| A hermit and his abstracts |

| ‘Hospital’+ series by Jeram Patel (1966) The exhibition, “The Dark Loam: Between Memory and Membrane”, largely focuses on Patel’s works from the 1960s when he worked inventively and extensively with a blowtorch on plywood sheets. His violent confrontations with the material, which brought out its inner surface, were echoed in his brilliant, if dark, etchings of amoeba and the human anatomy. His “Hospital” series has been described as “perhaps some of the best works produced by an Indian artist ever”. The show, the last of the trilogy of retrospectives by KNMA of underexposed abstract artists, culminates in his creations from the 2000s, which are brighter. “Jeram Patel: The Dark Loam: Between Memory and Membrane” can be viewed at KNMA, New Delhi, till December 20 |

)