I still remember that night, many years ago, on the banks of the Indus on the outskirts of Leh. A full moon glowed silver, bright enough to read by. As I gazed upon a footbridge festooned with hundreds of prayer flags, I felt as if I was under a strange magic spell, as if anything could happen at that moment. I often rewind to that moment. For years, I hesitated to return, fearing that Ladakh may have changed beyond recognition. But early this summer, when planning our annual family vacation, I decided to lay the old ghost to rest and show off Leh to my family, who hadn’t been there before.

Since my fondest memories of Leh are of traipsing in its impossibly green outskirts and the Indus valley, I decide to book yurts (Mongolian style tents) overlooking the snowy Stok ranges at Ladakh Sarai, about eight kilometres from town. Lush environs, comfortable tents, great service and innumerable walking opportunities make the Sarai a serendipitous choice.

The very first day, we acclimatise with a short walk to Saboo, the pretty village where we’re located. We learn it is a model village being developed under the prime minister's reconstruction programme for Jammu & Kashmir, which means it has proper drinking water supplies, electricity and tarred roads. Although flattened by the 2010 cloudburst that took over 15 villagers’ lives, Saboo is now a picture of tranquillity, with children playing on the bridge and women chattering gaily. Wild roses fill the air with their scent and cheeky blue magpies flit amongst willow trees, their trunks twisted and gnarled in all manner of shapes. We turn back as the sunset tinges the snow peaks around us with an impossible shade of pink, and I’m happy that the magic that Leh had once worked on me is alive and kicking.

One of the monasteries I’d spent a lot of time when I was here last was Hemis, the richest and arguably most important amongst the plethora of monasteries in Ladakh. I’m particularly excited that our present visit coincides with its annual festival, where the mask dance, Chham, is performed. This is an elaborate affair with in which masked dancers representing forces of good and evil, whirl and twirl in the crowded courtyard filled with monks, devotees and gawking tourists. Chham is essentially a tantric ritual, and performed only in monasteries that follow Tantric Vajrayana teachings. I look at the old Thangka fluttering above us, a rare painting that is only displayed during the festival, and wonder about all the secrets that Hemis hides. They say that hidden in its libraries are accounts of the journey through Tibet of a saint named Issa, the Islamic name for Jesus. Nobody has verified this story till date, but many believe that maybe, Christ once traversed these high mountain ranges.

I feel the same sense of déjà vu as we drive past myriad white chortens, Buddhist memorial markers, to Thikse Monastery. While Hemis might be the richest and most important, this monastery, with its stunning two-storey statue of Maitreya Buddha, has a sense of immeasurable peace. As we climb up its high steps to the rooftop, the sounds of people fade away. The landscape is stunning, for the monastery affords great views of the Indus Valley and mountain ranges all around us. Finally, we find ourselves in front of the Maitreya Buddha, where a talkative lama advises tourists where they can hang prayer flags in their tenth-floor flat in Bengaluru. “I always tell people,” he says with impressive gravitas, “to tie them from their balcony to their Tata Sky antenna!”

We descend the steps of the monastery and enter a chamber where a lama is guiding a group meditation. After a couple of minutes, I find that my heartbeat has become one with the steady beat of the drum, and even though I haven’t a clue what he’s chanting, I’m mesmerised by the voice of the lama. I look around at the motley bunch of meditators — a noisy family from Maharashtra, French trekkers, yuppies from Bengaluru and us, of course. It is as if the chanting and drumbeat has united us into a group jointly pondering the mysteries of our existence.

More days, more monasteries and more food later, it is time to bid adieu to Ladakh again. In the crowded confusion of delayed flights and long queues at the tiny Kushok Bakula Rimpoche airport in Leh, I fancy I can hear echoes of a distant drum. It makes me sigh, for this return to Ladakh has only made me want to return yet again…

Since my fondest memories of Leh are of traipsing in its impossibly green outskirts and the Indus valley, I decide to book yurts (Mongolian style tents) overlooking the snowy Stok ranges at Ladakh Sarai, about eight kilometres from town. Lush environs, comfortable tents, great service and innumerable walking opportunities make the Sarai a serendipitous choice.

The very first day, we acclimatise with a short walk to Saboo, the pretty village where we’re located. We learn it is a model village being developed under the prime minister's reconstruction programme for Jammu & Kashmir, which means it has proper drinking water supplies, electricity and tarred roads. Although flattened by the 2010 cloudburst that took over 15 villagers’ lives, Saboo is now a picture of tranquillity, with children playing on the bridge and women chattering gaily. Wild roses fill the air with their scent and cheeky blue magpies flit amongst willow trees, their trunks twisted and gnarled in all manner of shapes. We turn back as the sunset tinges the snow peaks around us with an impossible shade of pink, and I’m happy that the magic that Leh had once worked on me is alive and kicking.

One of the monasteries I’d spent a lot of time when I was here last was Hemis, the richest and arguably most important amongst the plethora of monasteries in Ladakh. I’m particularly excited that our present visit coincides with its annual festival, where the mask dance, Chham, is performed. This is an elaborate affair with in which masked dancers representing forces of good and evil, whirl and twirl in the crowded courtyard filled with monks, devotees and gawking tourists. Chham is essentially a tantric ritual, and performed only in monasteries that follow Tantric Vajrayana teachings. I look at the old Thangka fluttering above us, a rare painting that is only displayed during the festival, and wonder about all the secrets that Hemis hides. They say that hidden in its libraries are accounts of the journey through Tibet of a saint named Issa, the Islamic name for Jesus. Nobody has verified this story till date, but many believe that maybe, Christ once traversed these high mountain ranges.

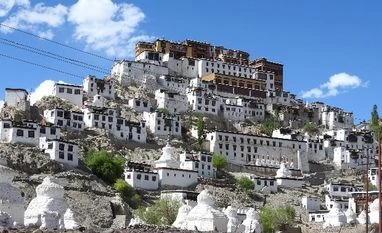

Thikse Monastery

I feel the same sense of déjà vu as we drive past myriad white chortens, Buddhist memorial markers, to Thikse Monastery. While Hemis might be the richest and most important, this monastery, with its stunning two-storey statue of Maitreya Buddha, has a sense of immeasurable peace. As we climb up its high steps to the rooftop, the sounds of people fade away. The landscape is stunning, for the monastery affords great views of the Indus Valley and mountain ranges all around us. Finally, we find ourselves in front of the Maitreya Buddha, where a talkative lama advises tourists where they can hang prayer flags in their tenth-floor flat in Bengaluru. “I always tell people,” he says with impressive gravitas, “to tie them from their balcony to their Tata Sky antenna!”

We descend the steps of the monastery and enter a chamber where a lama is guiding a group meditation. After a couple of minutes, I find that my heartbeat has become one with the steady beat of the drum, and even though I haven’t a clue what he’s chanting, I’m mesmerised by the voice of the lama. I look around at the motley bunch of meditators — a noisy family from Maharashtra, French trekkers, yuppies from Bengaluru and us, of course. It is as if the chanting and drumbeat has united us into a group jointly pondering the mysteries of our existence.

More days, more monasteries and more food later, it is time to bid adieu to Ladakh again. In the crowded confusion of delayed flights and long queues at the tiny Kushok Bakula Rimpoche airport in Leh, I fancy I can hear echoes of a distant drum. It makes me sigh, for this return to Ladakh has only made me want to return yet again…

)