I have a confession to make. Although I’ve been a Leonardo da Vinci fan for over 20 years and I’ve made my pilgrimage to almost every city where his works are displayed (barring St Petersburg and Krakow), I didn’t actually want to see the “The Last Supper”.

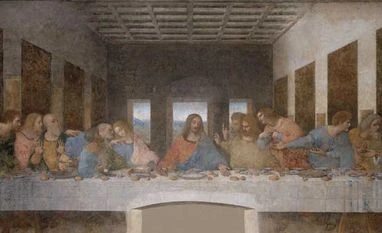

The painting has been notoriously badly treated over the past six centuries, including by the painter himself. He created his own doomed technique for mural painting so that he could spend three years painting each detail perfectly on the brick wall of the dining hall in the Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie.

The bricks reacted to changes in temperature, humidity and moisture and the pigment broke loose from the base. A process of decay set in, and within 20 years of its completion in 1498, it had begun to decay. Within 50 years, “The Last Supper” was an unrecognisable ruin.

The bricks reacted to changes in temperature, humidity and moisture and the pigment broke loose from the base. A process of decay set in, and within 20 years of its completion in 1498, it had begun to decay. Within 50 years, “The Last Supper” was an unrecognisable ruin.

Things didn’t improve for the painting. The monks cut a doorway through the bottom of the painting, which they later bricked up. Then, a curtain was hung over the painting to protect it. Instead, it trapped moisture on the surface, and whenever the curtain was pulled back, it scratched the flaking paint.

Over time, the room was used as an armory and then a prison. French troops threw stones at the painting and climbed ladders to scratch out the Apostles’ eyes. A restorer who thought it was a fresco damaged the centre section, which he then tried to reattach with glue. And during World War II, it was used for target practice by American soldiers.

The topic is equally sad. The painting portrays the moment when Jesus tells his disciples that one of them has betrayed him. As someone who loves food, I always wondered why he would announce this over dinner, and why da Vinci would think that this was an ideal topic for the monks to look at while eating.

But somehow, things conspired to put me in front of the painting. I had no plans to go to Milan and tickets to visit the painting were sold out months in advance. But I spotted an offer of one ticket to see the Biblioteca Ambrosiana, the second oldest public library in the world, and “The Last Supper”. It meant that I’d have to travel to Milan alone for a day to see the painting, but who said pilgrimages were easy?

If all this wasn’t difficult enough, the convent isn’t on any direct metro line from Milan’s central train station. Instead, I have to take the metro till the gorgeous Milan Cathedral, and then locate the old library on a small street nearby.

The Biblioteca houses “Portrait of a Musician” and “Salvatore Mundi” – two of da Vinci’s 16-odd surviving paintings – as well as “Portrait of a Lady in Profile”, a disputed work. There’s something even more valuable. The Codex Atlanticus –1,119 leaves of drawings and writings that da Vinci wrote from 1478 to 1519 on topics ranging from optics, flight, weaponry, mathematics, botany and musical instruments.

The legend goes that his Florentine patron, Lorenzo de’ Medici, sent da Vinci bearing a silver lyre in the shape of a horse’s head as a gift to secure peace with Ludovico Sforza, the Regent of Milan. But first da Vinci sent the Regent a famous letter describing the many things that he could achieve in the fields of engineering and weaponry. It mentioned in passing that he could also paint.

But somehow, things conspired to put me in front of the painting. I had no plans to go to Milan and tickets to visit the painting were sold out months in advance. But I spotted an offer of one ticket to see the Biblioteca Ambrosiana, the second oldest public library in the world, and “The Last Supper”. It meant that I’d have to travel to Milan alone for a day to see the painting, but who said pilgrimages were easy?

If all this wasn’t difficult enough, the convent isn’t on any direct metro line from Milan’s central train station. Instead, I have to take the metro till the gorgeous Milan Cathedral, and then locate the old library on a small street nearby.

The Biblioteca houses “Portrait of a Musician” and “Salvatore Mundi” – two of da Vinci’s 16-odd surviving paintings – as well as “Portrait of a Lady in Profile”, a disputed work. There’s something even more valuable. The Codex Atlanticus –1,119 leaves of drawings and writings that da Vinci wrote from 1478 to 1519 on topics ranging from optics, flight, weaponry, mathematics, botany and musical instruments.

The legend goes that his Florentine patron, Lorenzo de’ Medici, sent da Vinci bearing a silver lyre in the shape of a horse’s head as a gift to secure peace with Ludovico Sforza, the Regent of Milan. But first da Vinci sent the Regent a famous letter describing the many things that he could achieve in the fields of engineering and weaponry. It mentioned in passing that he could also paint.

After this appetiser, it is time to find my way to the main course. This involves taking one of Milan’s old style trams that have been around since 1881. It is hot and uncomfortable, but in typical Italian fashion, the whole compartment soon knows where this tourist, anxiously clutching her map and gazing at each street sign, wants to go and I am led off the tram at Corso Magenta, in the historic centre of Milan.

Sure enough, also in typical Italian fashion, in the middle of a modern street filled with shops, and just past a bright red church, is a large paved area. This is the front of the Santa Maria delle Grazie complex, a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Entering the humidity and light controlled filtering chamber in which the painting resides is an event in itself. Only 30 people at a time are allowed through the two automatically sealed doors. It’s a tight crush but the second door won’t open till the first one is closed. When the light above you finally goes green, people rush forward to take in the magnificence.

More From This Section

The real “The Last Supper”, despite being the most reproduced painting in the world, is magnificent. Its 15 feet by 29 feet long and it rises above you so that it’s an extension of the huge chamber. It’s said that you can still find the nail marks in it that da Vinci used to give the painting its famous perspective.

You can imagine that you’re sitting at the foot of the table and staring up at the young and beautiful Jesus sitting alone in front of you, as his disciples move away from him in horror. His calm contrasts with their agitation. Only John, whose clothes mirror his, sits in acceptance. All the faces were modelled on real people. Judas was modelled on a criminal. Jesus is unfinished. Da Vinci felt that he wasn’t worthy to complete him.

You can imagine that you’re sitting at the foot of the table and staring up at the young and beautiful Jesus sitting alone in front of you, as his disciples move away from him in horror. His calm contrasts with their agitation. Only John, whose clothes mirror his, sits in acceptance. All the faces were modelled on real people. Judas was modelled on a criminal. Jesus is unfinished. Da Vinci felt that he wasn’t worthy to complete him.

Despite the faded colours, all except one face is clear. You can only make out the ear on Judas’s face. But he clutches coins in his hand, spilt salt lies before him and his hand is reaching out to dip into the same dish as Jesus, which Jesus said would be the mark of his betrayer.

Through three windows behind them, the image stretches back into an ethereal Tuscan landscape that ends in a misty horizon. A tapestry on the sides binds the painting so that it looks like a room.

Through three windows behind them, the image stretches back into an ethereal Tuscan landscape that ends in a misty horizon. A tapestry on the sides binds the painting so that it looks like a room.

The bread, fish, wine and salt containers look lifelike and the tablecloth is clearly textured, marred only by the door that bisects the bottom of the picture into two. At the other end of the chamber is a painting of the “Crucifixion” by Milanese painter, Giovanni Donato da Montofarno.

Although it’s the same size as da Vinci’s painting and far more detailed, it’s not memorable. As your gaze returns to stare at the emotions on each of the disciple’s faces, you see the walls around the paintings are pockmarked with bullet holes. And you realise how lucky you are to be able to see this painting.

Although it’s the same size as da Vinci’s painting and far more detailed, it’s not memorable. As your gaze returns to stare at the emotions on each of the disciple’s faces, you see the walls around the paintings are pockmarked with bullet holes. And you realise how lucky you are to be able to see this painting.

The bell goes off and we walk reluctantly out of the door into a brightly lit modern pathway, tears still drying on my face. But this is Italy. On the way to catch the metro back to the Central Station, I stop for another Italian masterpiece – a gelato.

)