There is a gnawing temptation to call it a “comeback”. It was a lot of things — redemption, revenge, retaliation, rectification — but comeback wasn’t one of them. The rebound came over two years ago, when Tiger Woods, incapacitated by physical pain and worn down by the mental lacerations of a life spent in the limelight, displayed the unlikely fortitude to give golf another go.

A broken home, a vile media trial for sexual misadventures, four traumatic back surgeries, and the unspeakable wretchedness of being ranked 1,199 when you once ruled the world would’ve broken most. That Woods found a way to swing a golf club and handle the ordeal of playing 18 holes again — let alone winning the Masters for a fifth time against a group of talented young men whose careers he himself inspired — was the comeback.

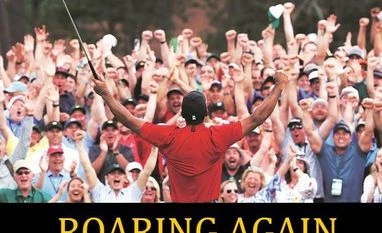

That is perhaps why Sunday invited less silly sobbing and more wholehearted joy. More acknowledgement and less bewilderment. Less hyperbole and more hope. Woods himself marched through the crowds like a crazed teenager after sealing the win, exulting wildly, high-fiving euphoric fans, and sporting the grin of a man who had just won a billion-dollar lottery with a ticket he had discovered in the trash. This was a rare outpouring of emotion from a player who once ripped entire tournaments apart, relegating others to the status of walk-ons meant to just make up the numbers. He was imperious, smug even — golf was his thing and there was no one better at it than him.

Just that around 2010, when Woods’ life first started showing signs of falling apart, a new breed of golfers emerged, one that came minus the mental baggage of being tormented by Woods on a golf course. They never had the privilege of witnessing Peak Tiger — an athlete with the menace of a North Korean general and the ruthlessness of a KGB spy. As Woods’ own game, engulfed by public scandal, nosedived, the younger bunch flourished, liberated from playing in the shadow of a virtual golfing ogre. Golf went from being a one-man industry to a sport increasingly occupied by an ensemble cast; it was more interesting sometimes, but without its dominant talisman, it was also dull.

That’s why they packed the galleries in Augusta this past Sunday in the thousands, waiting for a moment they thought would never arrive. I myself tuned in for a final round of golf in since forever; in the pre-Tiger-adultery age, I almost never missed one. That is the kind of sway Woods still has over fans even after all these years, repeatedly ensuring that an elite sport like golf has enough room for the masses.

A 21-year-old Woods receiving his first Green Jacket from Nick Faldo in 1997. Photo: Reuters

That is not to say that the man himself hasn’t undergone change. The Woods we saw last weekend wasn’t anything like the all-conquering juggernaut that reset the limits of golf for over 10 years starting the previous millennium. This was a more human, kinder version of Woods, one who knew he was no longer the young, frantic pace-setter but a canny veteran capable of pouncing on any mistakes he saw.

At Augusta National, that mistake came from Francesco Molinari, the current Open champion who, interestingly, played in a Masters group with Woods while caddying for his brother, Edoardo, way back in 2006. As the skies briefly opened up late on Sunday, Molinari, the leader at the time, saw his world come crashing down. It was the Italian’s water-bound approach on the 12th that helped Woods stay afloat. The 43-year-old cashed in, never relinquishing the lead from that point on.

That’s the thing about Woods. Physically, he’s not the same startling specimen that made his peers realise that the gym was as important for a golfer as for any other athlete, but mentally, he can roam spaces few can fathom. Never won a tournament from behind after 54 holes? No problem. Not won the Masters for 14 years? No problem. Not won a major for more than a decade? No problem. Everybody writing you off? No problem. Woods, for long, was the problem himself; now he’s the one no one can solve.

All of this has been made possible by, among other things, a new swing, restructured to limit pain and maximise productivity. Doing that at his age is like asking Roger Federer to start playing a double-fisted backhand, or persuading Virat Kohli to change his batting stance overnight. The short game can still be a mess at times — as Woods discovered in the third round — but his feats of escapology in clutch situations continue to be the gold standard in all of golf.

Even as his golfing pedigree remains undimmed, Woods’ personality has seen a quiet transformation. He looks happier now, joking on the course and making new friends. The brutal approach of his youthful years seems like a thing of the past. He now plays golf the way he had always imagined it when he first picked it up as a three-year-old boy: full of fun and with infectious enthusiasm.

That, for the sake of everyone’s sanity, mustn’t be confused with a moral metamorphosis. We genuinely hope that those sessions of sex addiction therapy helped Woods regain much of what he lost during those dark times, especially his family and friends. But it’d be unfair to equate his return to the acme of golf with a tale centred on righteousness. The perfidious lover and irresponsible family man was the most devastating golfer we have ever seen, and it will be unfair to suggest that he owed us fans this improbable return after all that he had done. As Marina Hyde wrote in an excellent piece in The Guardian earlier this week, “Part of the amusing, exhilarating, exasperating nature of sport is that awful people can be wonderful at it.” Woods does not need a medal from the moralists.

Having said that, whatever emotional space Woods is in, we pray he stays there for as long as he can. There is no better sight than him charging off to the fairway after hitting his tee shot, fierce determination writ all over his face; or pumping those fists — and those bulging biceps — after sinking a putt. It is sporting theatre of the magisterial variety. Golf needs him, perhaps more than he needed it in the years following his downfall. And since he’s on the up, it’s time to talk about records again.

In a homemade video shot when he was about five years old, a beaming Woods is seen saying, “I’m going to beat Jack Nicklaus.” It seemed impossible only a few years ago, but Nicklaus’ haul of 18 majors once again looks within Woods’ reach (he has 15). Nicklaus was there in 2005, when Woods pitched in for a most outrageous birdie on the 16th at Augusta, on his way to a fourth Masters victory. The commentator that day, baffled by Woods’ genius, excitedly exclaimed: “In your life, have you seen anything like that?” We hadn’t, until that same man did it again this past Sunday, 14 years on.

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)