Artists are said to have their head in the clouds. Auria Kathi, a poet and artist in training, said so herself. Sometime during the turn of the year, Auria Kathi joined Twitter and Instagram to showcase her work. Her first tweet, appropriately obscure, read: “I am an abstract artist living in the clouds. I write a poem and make an image. My art, I feel, is ‘unsettling’. You think you know but do you?”

Since January, Auria Kathi has been posting a haiku-style poem (haikus are three-line, 17-syllable Japanese poems) and a piece of abstract art to go with it. You can set your watch to the exercise: her work appears just after 7pm every day and will continue to do so till the end of this year.

“I hate when people/make fun of the “shitty” things/we do for free stuff,” reads one of her latest works. Auria Kathi has never interacted with anyone in the eight months she’s been around or even “liked” a comment — both fundamental to building a strong online presence — and yet she has a little more than 1,720 highly attentive followers on Instagram.

Auria Kathi, India’s first AI poet-artist

That’s because Auria Kathi is a fascinating creature — India’s first artificial intelligence (AI) poet-artist. AI is the simulation of human intelligence processes by machines. And Auria Kathi is an anagram derived from “AI haiku art”.

This October, digital prints of Auria Kathi’s art will be displayed at the 12th edition of the Florence Biennale in Italy. She’ll be one amongst 60 artists from over 70 countries to showcase her work to an international audience.

Despite the fact that it can be challenging to explain that Auria Kathi doesn’t physically exist in the “real” world, her makers Fabin Rasheed and Sleeba Paul say the experience has been overwhelming. The most common questions directed at the duo revolve around her “reality”. If she isn’t real in the traditional sense, how can she devise poetry or make abstract art?

Artwork by Auria Kathi

Art generated by artificial intelligence isn’t an entirely new concept. Discussions on whether work created by artificial intelligence could be considered truly “creative” have been around for as long as science fiction. Speculation around whether a true art collector would buy something created by an artificial “mind” went for a toss when an AI-generated artwork, the portrait of a portly gentleman named Edmond Belamy, sold for $432,500 late last year. Sold by auction house Christie’s, the price was nearly 45 times over its original estimation.

“Her face is artificial, her art is artificial, she’s completely artificial,” says Paul, 27, co-creator of Auria Kathi and a resident of Kochi, Kerala. In any other context, Paul’s words would have been considered dismissive and derogatory, but he’s only stating facts here. Trained on a dataset of 3.5 lakh haikus and with a digital face generated by another dataset of pictures of Hollywood celebrities, that’s exactly what Auria Kathi is. She’s someone who currently exists on a platform hosted by tech giant Microsoft, and yet her work is as real as that of any human.

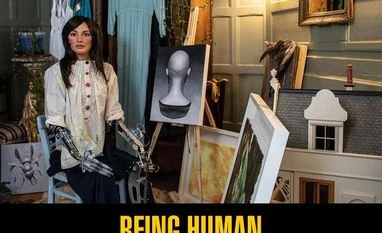

An ocean away, Auria’s contemporary, Ai-Da, a humanoid robot with bionic arms and a head full of flowing hair, has already had her first exhibition earlier this June at the University of Oxford’s Barn Gallery in the UK. The show, called Unsecured Futures had a collection of drawings, paintings, sculptures and videos. Her work was snapped up even before the exhibition began, generating well over a million pounds, says Ai-Da’s inventor, British art dealer Aidan Meller.

“We wanted a project that would engage audiences in topics of our times. Robotics and AI are vital in shaping our future. Having an artist that is an ultra realistic AI robot meant having a project that encourages discussion,” says Meller.

Ai-Da’s intriguing persona, says her maker, reflects the uncertainty of our online worlds. “Who is Ai-Da? This is the same question we ask ourselves when we are online — who are we dealing with when we interact with avatars and chatbots, where social media allows us to orchestrate our own image.”

It’s hard to predict the future with AI in the picture. “A lot of scepticism around AI stems from the theory that once machine learning and AI catch fire, human jobs — and eventually humans — will be made redundant,” says Santhosh Pillai. Based in Redmond, in Washington, USA, Pillai is the project manager for Microsoft’s Azure Machine Learning service. It was Pillai who realised that Auria Kathi could be hosted on Microsoft’s platforms. “Applications such as Auria Kathi will capture the imagination of software developers and machine learning enthusiasts and will spark a lot of interest in the common man,” he says.

Only a few days ago, at a meeting organised by the Kerala Management Association in Kochi, a participant stood up to ask if an AI agent was capable of replacing beloved music composer

A R Rahman. Paul had to explain that though AI can make music (it can, for instance, mesh Mozart with Lady Gaga perfectly acceptably), AI could perhaps be better used to assist Rahman instead. “The essence of creativity lies in not just repeating or simulating part or whole of an inspiration, but also being able to create surprises, new connections and something that isn’t repeatable, says Rasheed.

Sleeba Paul (right) and Fabin Rasheed

It is due to concerns such as AI taking over that the idea of “Responsible AI” has come into play, says Pillai. “Microsoft and several AI pioneers are committed to make sure we follow ethical practices around AI.”

Another question that engages viewers’ minds is whether Auria understands what she is creating. “It all depends on what understanding is,” says Rasheed, Auria’s co-creator from Kerala’s Alleppey and an independent designer who has worked with Adobe. “In a way she does understand that she’s creating something meaningful, but she doesn’t know what that is in a real context. Understanding is subjective.”

The question of whether a machine perceives things like humans do is only the beginning of a future brimming with such discussions, feels Bengaluru-based Harshit Agrawal, a new media artist and one of the first Indians to incorporate AI into their work (his works were part of the country’s first AI art exhibition held at the Nature Morte gallery in Delhi last year).

The explorations he’s carried out with AI installations include one which explores a “machine’s cultural underpinnings”. A machine is, after all, built and defined by the datasets it is fed by humans. It’s interesting to learn that the machine, however “intelligent”, isn’t free of the leanings and biases humans are marked by.

Harshit Agrawal, whose masked reality series features an interactive installation that reflects one’s expressions

In one of his projects (Masked Reality), Agrawal uses images of different Indian masks, especially those from the disciplines of Kathakali and Theyyam. The interactive half of the fascinating project involves the machine reading a human’s expressions in real time and changing the mask’s expressions accordingly. And in another one (Author(rise)), he explores what happens when a human and a machine collaborate. For this, Agrawal had fed the machine, which was connected to an electronic pen, a dataset of philosophy texts and a dataset of human handwriting. A person could start writing on paper using that pen, and in 15 seconds the machine would take over and attempt to express its thoughts through the person’s hand. In 2017, when Agrawal asked the participants at the Ars Electronica Festival in Linz, Austria, who the work belonged to, they claimed ownership, even though it was the machine’s thoughts that had finally filled the paper. The question of the “real” author remains open to discussion.

In the meantime, as they prepare for the Florence Biennale, Auria’s creators say they’d like the entity to be “more human”, and perhaps even mimic human behavior. Ethics, and the ability to distinguish right from wrong, are the societal learnings that shape us as humans, says Paul. The quest to experiment with AI is progressing by asking precisely the question that has been asked since the beginning of history: What is it that makes us human?

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)