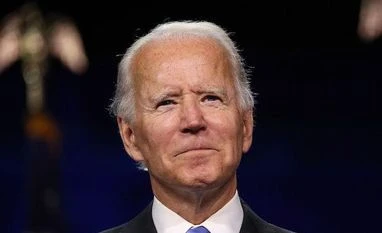

Wall Street has made its peace with a Joe Biden victory, taking comfort in his decades-long political career in which moderation is a prevailing trait. But it’s nervous about his more liberal allies.

Finance executives will be closely watching how Biden handles the coming internal Democratic fight between centrists and progressives that threatens to increase regulation and dent profits.

Firms are counting on his business-friendly inner circle -- a group that includes long-time Democratic stategists, corporate lawyers and former lobbyists -- to exert the most influence in selecting nominees for agencies like the Treasury Department and the Securities and Exchange Commission that manage the economy and police the markets. Middle-of-the-road candidates have a key advantage: They’ll have a much easier path to confirmation in a Senate that appears likely to remain in Republican hands.

Yet liberal Democrats, inspired by Senator Elizabeth Warren’s focus on wealth inequality and distrust of big banks, are intent on getting like-minded officials into those jobs. They argue that in a Democratic administration, the president must pick regulators with strong records of prioritizing average Americans over financial titans.

“Personnel is policy,” and progressives have come into the fight “armed with a bazooka,” said Stephen Myrow, managing partner of Beacon Policy Advisors, a Washington-based firm that tracks regulatory and legislative proposals. “You will certainly see some re-regulation.”

Hanging in the balance could be the reach of post-crisis rules that were eased during the Trump administration. Over the past four years, adjustments to complex requirements like capital levels, collateral for derivatives trades and brokers’ legal responsibilities have saved banks tens of billions of dollars. Firms are also concerned there will be a fresh focus on investigations, a clampdown on executive pay and that regulators will be slow to lift restrictions on dividends and share buybacks that were implemented due to the pandemic.Biden has already tapped former Commodity Futures Trading Commission Chairman Gary Gensler and KeyBank NA executive Don Graves to examine financial regulatory agencies as part of the presidential transition, according to a person familiar with the matter. Gensler’s role should appease progressives, as he gained a reputation for standing up to Wall Street during President Barack Obama’s administration. Conversely, the involvement of a long-time banker like Graves will probably reassure financial firms.

Though banks, private equity firms and hedge funds mostly escaped the spotlight during a presidential campaign dominated by coronavirus, their top managers and Washington lobbyists -- many of whom donated to Biden’s run -- are now emerging from the shadows to offer lists of preferred agency chiefs.

In a nod to Biden’s pledge to have a diverse administration, their candidates include women and people of color who have experience at investment firms. A number, too, have worked under Obama, making them a known quantity to Wall Street.

The progressives, however, say they plan to draw the line at regulators in the vein of Robert Rubin, Timothy Geithner or Lawrence Summers. The activists have also been busy doing opposition research, paying particular attention to employees at private equity firms and asset manager BlackRock Inc., which they contend holds too much sway in Washington. Progressives say they plan to oppose most industry-connected candidates, even for lower-level jobs.

Still, with the chances of Democrats taking the Senate looking challenging, the financial industry might dodge some of the most arduous measures that Washington could have thrown at them. That includes higher corporate taxes, new levies on stock trading and high-profile Senate hearings were CEOs would face a barrage of uncomfortable questions.

Along with the slate of new agency chiefs, the Biden victory will impact financial companies large and small in numerous ways. What follows is a look at several agencies and policy areas that will be on the front burner as the Biden administration begins in January.

New Constraints on Pay?

More than a decade since Congress passed the Dodd-Frank Act, there’s still a major requirement that’s never been finished: a mandate that financial regulators implement constraints on executive pay at banks, brokerages, asset managers and other firms. The purpose is to rein in compensation practices that encouraged the kind of excessive risk-taking that caused the 2008 financial crisis. But regulators have proposed rules multiple times without ever settling on an approach.

While firms sought to get out in front of the rules by beefing up their own policies for clawing back bonuses and withholding deferred pay, watchdogs appointed by Biden could mandate requirements that are much tougher that those that companies have adopted.

A Private Equity Reckoning?

It’s no secret that private equity firms are No. 1 on the Democrats’ hit list for the finance industry. The lightly regulated investment companies are sure to face policy fights that could impact their business model, as well as the companies they own.

Democrats’ goal of imposing new taxes on buyout firms will face headwinds in the Senate. But it’s possible eliminating the carried interest loophole, which allows partners’ profits to be taxed at a lower capital gains rate rather than as income, could draw bipartisan support. Other tax targets that might imperil the industry, such as limiting the deductibility of the debt that is often piled on corporate acquisitions, seem doubtful.

Even without Congress, Biden’s regulators are expected to step up scrutiny of private equity and could issue new rules. Though some Trump holdovers could slow the process, the industry is likely to be reviewed by the Financial Stability Oversight Council, the powerful group of regulators led by the Treasury secretary. FSOC can put firms under Federal Reserve supervision or regulate industry practices that it deems potentially unsafe.

Lastly, Democrats in the House may turn to a “name-and-shame” agenda, by holding hearings and conducting investigations to highlight issues like bankruptcies of portfolio companies or the industry’s more controversial investments in health-care and private prisons.

A Reprieve on Taxes?

Trump’s 2017 tax cuts have been particularly beneficial for banks. Their effective rates used to be higher than those paid by non-financial companies and had more room to fall.

Biden has proposed an increase to the corporate rate that could result in the six biggest US banks paying an additional $9 billion in 2021, and much more in future years as their earnings recover from the pandemic. But it’s hard to see Republican senators supporting a tax hike.

A Reinvigorated CFPB?

Wall Street has already ceded the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau to the progressives, who want Warren’s brainchild to get much tougher than it has in the Trump years in policing mortgages, credit cards and other products. Warren herself is sure to play a role in picking its next director and one potential candidate is US Representative Katie Porter of California, an acolyte of the Massachusetts senator.

Banks are hoping that if a more liberal appointee is confirmed to run the CFPB, Biden may gain flexibility to pick moderates to take the helms of the Treasury Department, the Fed and the SEC.

Still, the CFPB won’t have a light-touch agenda like it did under Trump, when the agency’s budget was closely scrutinized and it focused on smaller payday lenders, mortgage firms and auto loan companies. Big banks are likely to get more attention, along with new rules and sanctions. That includes an expected effort to rein in overdraft fees – which bring lenders some $11 billion annually.

A Muscle-Flexing FSOC?

In the Trump era, FSOC strayed from its envisioned role of trying to spot risks that could cause another financial panic, focusing instead on ways to cut rules. Most think that will quickly change under Biden.

Its powers include the authority to designate a company “systemically important,” which puts firms under heightened Fed supervision. The council can also do the same for products or practices it believes are too risky, such as money market funds or securities lending. In addition, FSOC sets key oversight priorities. Biden’s regulators will be able to fill six of the 10 voting seats. Still, four Trump appointees, including the Fed chairman, will retain their jobs and can stay on for at least a year -- meaning any change may not come fast.

A Tougher SEC?

No watchdog matters more to Wall Street’s vaunted investment banks than the SEC, which will be at the center of the fight between progressive Democrats and moderates over the direction of financial regulation in the next four years.

Liberals would like to see former SEC Commissioner Kara Stein return to the agency as chairman. She is a vocal industry critic, who during her SEC tenure blasted bank fines as too weak and repeatedly questioned whether the agency should have placed more restrictions on products like leveraged exchange traded funds. Candidates favored by moderates include former SEC Commissioner Robert Jackson Jr. and Georgetown Law Professor Chris Brummer, who would be the first African American chairman.

Pain for Regional Banks?

Regional lenders such as US Bancorp, PNC Financial Services Group Inc. and Truist Financial Corp. are among those that have benefited most from the Trump administration, with regulators tailoring rules so that Wall Street banks got the toughest oversight. Biden appointees could revisit those rollbacks, though some Democratic lawmakers backed the relief that mid-sized lenders got under Trump. New watchdogs and Democrats might also exert more scrutiny on potential mergers involving regional banks. Such lenders, however, can count on GOP allies in the Senate to help fend off attacks.

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)