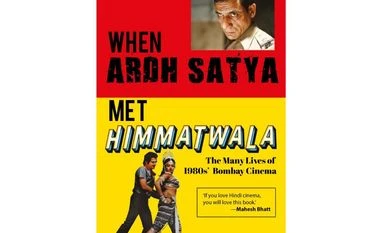

When Ardh Satya met Himmatwala – The many lives of 1980s Bombay cinema

Avijit Ghosh

Speaking Tiger

Pages: 377

Price: Rs 599/-

If, like me, you grew up on 1980s Hindi cinema you will enjoy this book. Even if you didn’t grow up on it but have a mental image of silly, sleazy and funny films from that time, read it. It is the first proper, non-sneery, non-judgemental, affectionate and accurate chronicler of that time and the cinema it produced.

The eighties were a decade when we made kitschy films such as Himmatwala, Tohfa and Tarzan along with popular gems such as Ek Duuje Ke Liye, Naam, and Arjun among others. It was also the time when parallel cinema was doing well. Some of the best Indian films – Jaane Bhi Do Yaaro, Ardh Satya, Aakrosh, Bazaar, Chakra, Arth, Masoom are all from the eighties. The A, B and C grade then mingled freely to produce the potpourri that is Indian cinema in what is now acknowledged as one of the most miserable decades for the business.

What, then, does one make of this period? Why was it such a mish-mash? How did it come about? These are some of the questions that Avijit Ghosh’s third book on cinema attempts to answer. His earlier books are Cinema Bhojpuri (2010) and 40 Retakes: Bollywood Classics You May Have Missed (2013). In addition to this he has written two novels and writes on cinema for The Times of India.

Disclosure – Aeons back when I worked for (then) ABP group’s Businessworld magazine, Ghosh wrote on cinema for the group’s English paper The Telegraph. So, we were colleagues in a manner of speaking.

Ghosh contextualises the phenomenon that was eighties Bombay cinema by drawing from the socio-economic, political, and cinema history of that time. He explores the strong north and south interactions that produced scores of low-cost, garish but successful films like Himmatwala (remember those pots on the beach?), the great strike of 1986, the scourge of film piracy, and the running battle with the censors.

It was a time of 1,000-seater, mega theatres. Only a film that could fill these for weeks on end could hope to make money. But competition from TV, piracy from video parlours and cable operators showing the latest films had started hitting the business. The leakages from under-reporting (many theatres simply stamped your hand instead of giving a ticket) and piracy meant that a bulk of the money never came back into the system. This along with crazy levels of taxes made the business completely star and formula dependent.

Ghosh’s chapter on the Great Strike of 1986 that began on October 10 and ended a month later on November 10 was an eye-opener. Entertainment tax on film tickets was 177 per cent in Maharashtra. There was a surcharge that had been levied for Bangladeshi refugees during the 1971 war; it continued to be levied 15 years later. There was an additional levy on film prints after the first 12 copies, making it a disincentive to release the film widely. The strike ended with the government agreeing to many of the industry’s demands. The film business has rarely come together like this after that. As Ghosh says, “Bombay cinema in the eighties had multiple personalities. Organised resistance, albeit briefly, was one of them.”

After the economic and political background my favourite portions of the book are ones chronicling the rush of Hindi films made in the south and the rise of parallel cinema. It may be the Bengali in him, but Ghosh takes you lovingly through the evolution of what he calls New Wave 1.0. “In 1969, three movies emerged like nymphs out of a lake defying existing classifications in Bombay cinema: Mrinal Sen’s Bhuvan Shome, Basu Chatterjee’s Saara Akash and Mani Kaul’s Uski Roti…Over the next decade a bouquet of terms – Parallel cinema, Art, Arthouse, New Wave, Offbeat, Alternative, Meaningful, Experimental and (just) New – entered the lexicon to describe this fresh category,” he writes. The eighties lot is called New Wave 2.0.

To my surprise many of these were commercially successful too. This is because their costs were lower than popular films. Chakra, Ardh Satya. Aakrosh and Chashme Buddoor are listed among the most profitable films by Trade Guide, a trade magazine, says Ghosh. Ardha Satya released in 1983 was among the five biggest hits along with Andhaa Kanoon, Avtaar, Betaab and Coolie. These films relied on the National Film Development Corporation (NFDC) or on patrons like Manmohan Shetty. He funded Ardh Satya, Hip Hip Hurray, Aghaat, Chakra among others. NFDC played a truly progressive role in cinema development those days, even funding films that were critical of the state. Many of these films and the superstars of parallel cinema – Naseeruddin Shah, Shabana Azmi, Smita Patil and Om Puri -- won awards at festivals overseas and created a context for Indian cinema.

In the pre-streaming and global television era the big problem was getting distribution for alternative cinema. Theatres simply didn’t want to play these films. While NFDC stepped in to fund theatres, it didn’t quite work out since it did not have the kind of money needed to fund physical infrastructure.

Ghosh gets all the facts of the eighties Hindi cinema history well, and puts the material together beautifully. My only quibble: I wish it had more anecdotes, some of the hair-raising or funny stories from a time that we can look back at with affection.

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)