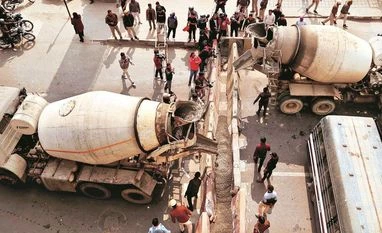

Once again, thousands of farmers are poised to march to New Delhi. Once again, barricades are being put up at Delhi’s borders. And once again, at the core of the issue is the minimum support price, or MSP.

The farmers want to press their long standing demand for legalising the MSP, agree upon when three farm laws were repealed in December 2021.

In July 2022, the government had set up a committee to make MSP more effective and transparent, to promote natural farming, and to change crop patterns keeping in mind the changing needs of the country. This committee is yet to submit a final report, but the recent price movement in critical crops such as wheat indicates the need for keeping market prices at reasonable levels to lessen the need for the support system.

In the last few seasons, though, the high market prices of cereal crops such as wheat have ensured that farmers preferred private buyers rather than selling to the government at the MSP, which was lower than the prevailing mandi rates. In the rabi marketing season of 2019-20 (April to March) to 2021-22, wheat procurement showed an increasing trend and reached a record level of 43.3 million tonnes in 2021-22.

However, procurement recorded a steep decline in the rabi marketing season of 2022-23 and reached a record low of 18.8 million tonnes, but increased by about 40 per cent to 26.2 million tonnes in 2023-24.

In both 2022-23 and 2023-24 marketing seasons, the procurement was less than the target, as market prices were higher than the MSP, and farmers preferred private buyers. That the crop was on the lower side contributed to the lower procurement by state agencies.

MSP and coming rabi

In the forthcoming rabi marketing season, say trade sources, market prices of wheat might remain above the MSP or close to it, as demand is firm, which would mean state procurement could remain below the estimates.

The Central government has announced a big increase in the wheat MSP for the 2024-25 marketing season, which starts in April, of 7.06 per cent, the highest in the Modi government’s tenure. Major wheat growing states such as Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan have announced big bonuses on wheat MSP, which will mean that the crop there will come at a premium to the prices in the other major growing states of Punjab and Haryana.

At present, wheat prices in the Delhi markets are ~2,500-2,500 a quintal.

In case of paddy, too, procurement was off to a slow start in 2023-24 (October-September), but has picked up pace. A bigger reason for the initial sluggishness could be concerns over the kharif crop, but some traders say the good prices for farmers this year in the open market for some varieties might have contributed.

Among other major forthcoming rabi crops, traders say, mustard prices, which dropped below the MSP for 2024-25, might remain low due to the large influx of cheap edible oils from Indonesia and Malaysia, taking advantage of the favourable duty structure, and a bumper harvest.

“In case of gram (chana), our expectation is that prices might remain above MSP, as sowing is down while the yield is not up to the mark,” a leading commodity analyst, told Business Standard.

MSP and farmer income

More than the immediate concern over MSP, it is its administration that remains a topic of debate.

Ever since the National Democratic Alliance came to power in 2014, commodities purchased under MSP have seen a significant rise. The number of farmers benefiting from the purchases has seen a jump. Still, there have been instances of farmers being forced to dump their produce for want of higher prices and in the absence of proper markets. Such problems are more acute in perishable commodities.

This has reignited farmers’ demand for legalising the MSP.

The Ashok Dalwai Committee on Doubling Farmers’ income, constituted by the Central government, has said that farmers’ income from both farm and non-farm sources must grow by 10.4 per cent between 2015-16 and 2022-23 in real terms (inflation-adjusted) and not nominally.

At current prices, the acceleration must be faster, at the rate of 15.9 per cent.

However, data shows real income of an agriculture household from all sources grew by around 21 per cent in the six years between 2012-13 and 2018-19. This means an average annual growth of just about 3.5 per cent in real terms.

In nominal terms, the incomes grew by 60 per cent between 2012-13 and 2018-19, which is an annual average of 10 per cent.

Legalising MSP

Several farmers’ groups and experts are convinced that it is doable and should be done given that agriculture incomes are growing at a pace not very healthy. But, given the vastness of India’s agriculture markets, the sheer quantum of produce the country generates every year and the multiple layers of intermediaries between the farmer and the end-consumer present stiff challenges.

“It is feasible, only that one needs the intent and will power to do so. There are multiple draft legislations available through which these can be implemented. But, the current government believes more in direct transfers such as PM-KISAN and not so much in MSP,” Sudhir Panwar, former member of Uttar Pradesh Planning Commission, told Business Standard. “The MSP structure is needed to give safety and security to farmers. Its implementation for all crops needs to

be guaranteed.”

C S C Sekhar, professor of economics at the Institute of Economic Growth, says legalising MSP is not a solution, but also that declaring MSP not backed by effective procurement is meaningless. Theoretically, he says, direct procurement is the best way to ensure MSP to farmers, but it suffers from two major constraints: Storage capacity and governance.

Further, Sekhar says that based on his analysis of 2019-20 production of 14 major crops as notified in the first advanced estimate for which the Centre declared the MSP, only 30 per cent of the crop can be directly procured by the government due to storage constraints. The rest must be absorbed by the market.

His calculations, published in the EPW, show that to provide deficiency price payment for the 14 identified crops, except wheat and rice, an annual subsidy expenditure of around ~2,31,403 crore at 2021-22 levels would be needed. There are also implementation inconsistencies.

Therefore, Sekhar advocates an income-based support system for non-staple food commodities. PM-KISAN, he says, can be an instrument.

“Leaving everything to the market is challenging, because we tend to think of farmers as a homogeneous entity, but in fact they are very heterogeneous. The small and medium farmers need protection and the large ones need markets,” he says.

Right now, both small and large are poised to march on New Delhi.

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)