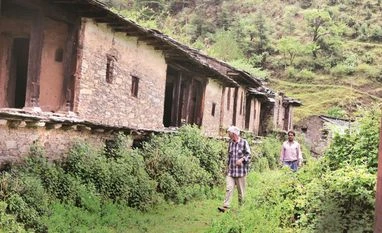

As the sun's golden rays pierce through the mighty deodars in the Himalayas, casting a warm glow over the valleys and hamlets below, an eerie silence hangs in the mountain air. Echoes of the past resonate through abandoned, crumbling homes that form what have come to be called Uttarakhand's ‘ghost villages’ – haunting relics of a fading existence.

The seriousness of the problem can be gauged from the fact that for the first time since elections started in India, 24 villages in the state did not have a single polling booth for the recent Lok Sabha polls. The state migration commission classified these hamlets as "uninhabited villages" between 2018 and 2022.

These villages are located in the districts of Almora, Tehri, Champawat, Pauri Garhwal, Pithoragarh, and Chamoli. Almora, incidentally, had the lowest voter share among the state's five Lok Sabha seats.

This is not a new phenomenon in Uttarakhand, where the number of 'ghost villages' is on the rise. According to the 2011 Census, the last, a staggering 1,048 villages across the state stand deserted, devoid of human presence, while another 44 cling to a mere whisper of life with fewer than 10 residents each. This mass exodus has left an indelible mark on the region's economic and cultural fabric, a solemn reminder of the fragility of a way of life that has endured for generations.

It has been more than 12 years since the 2011 Census. The film, "Ek Tha Gaon" (Once Upon a Village) by Srishti Lakhera, which was adjudged the best non-feature film at the National Film Awards 2023, provides a poignant glimpse into this reality, depicting the village of Semla in the Tehri Garhwal region, where only seven residents remain.

Films like "Yakulaans" by Pandavaas Production capture the profound loneliness and nostalgia experienced by those few remaining residents, as the elderly protagonist converses with himself, his cattle, and stray animals, accompanied by the melancholic strains of folk songs that echo through the deserted streets.

As the filmmakers say, Yakulaans shows a liberal, progressive view but is also filled with nostalgia, encapsulating the bittersweet essence of a way of life that hangs precariously in the balance, its future uncertain.

"Logon ne kheti chhod di, gaon jungle ban gaye (People have abandoned farming, villages have become jungles)," laments Rajeshwari Bhandari, a former head of Mishni Gaon in Pauri district.

Another resident, Devi (she gives only her first name), who once donated her land for a hospital, now watches helplessly as the facility's lack of essential services like X-ray and ultrasound machines forces residents to travel to places as far as Srinagar for treatment.

The outmigration

At the heart of this exodus from villages is the lack of economic opportunities.

"We did not invest in any employment-intensive sector, and that robbed the youth of their aspirations," rues Rajendra Prasad Mamgain, an economist at Doon University.

Agriculture, the traditional backbone of these villages, has been crippled by low productivity, land scarcity, and fragmented landholdings. "Agricultural fields are attacked by monkeys and other animals," says Jagat Singh Rawat, a retired headmaster from Dwarikhal block in Pauri Garhwal.

The absence of sustainable employment has triggered a steady exodus of the youth to cities and towns in search of better prospects. "People took their wives and kids, and left the land," says Rawat, underscoring the severity of the outmigration that has left entire villages bereft of their lifeblood, their homes and fields abandoned to the elements.

Consequently, local businesses have shuttered, their doors forever closed to the winds that now whistle through the deserted streets. Essential services like healthcare and education do not exist.

The impact on education has been equally dire. Tajbar Singh Negi, an armyman who lives in the Rikhnikhal block of Pauri Garhwal, notes, "Some colleges have more teachers than students, leading to a demotivating environment."

The economic loss associated with these ‘ghost villages’ remains largely unquantified, says Mamgain. "No major study estimates the economic losses."

However, the consequences are evident in the declining property values and the reluctance of natives to sell their ancestral lands.

"Natives don't see any profit in selling their land,” Mamgain says. “The average landholding per household is very small. It is less than 2 acres for more than 80 per cent of the population, and that is also scattered."

A Rural Development and Migration Commission was set up in 2017 to tackle this issue. However, the tide of migration continues unabated. "[There is] no holistic approach, no strong coordination between departments," critiques Mamgain, calling for a comprehensive strategy that integrates employment generation, infrastructure development, and policy reforms.

Mamgain is involved in the hill policy, which, under former Uttarakhand chief minister B C Khanduri, looked to focus on small industries in the region. But there are problems.

Mamgain says in the name of industry, the focus is mainly on solar energy. “We are just capturing the barren hills for profit,” he says, highlighting that the locals aren’t even hired to repair these plants. “The mechanics are largely from Madhya Pradesh and Bihar.”

Academic and food historian Pushpesh Pant lists the multiple interlinked factors that drove the outmigration from Uttarakhand's villages: ecological disasters that caused "the ground to sink" in places like Garbyang on the Indo-Tibet border in the 1950s; disruption of traditional livelihoods like trans-border trade after the 1962 Indo-China war when "these villages lost their livelihood" as the "Indo-Tibet trade was stopped"; lack of economic opportunities pushing youth to seek jobs and education elsewhere; and reservation benefits incentivising migration away from the villages.

Pant expresses grave concerns about “ill-conceived” tourism development disrupting the fragile ecology and leading to crass commercialisation rather than authentic preservation of cultures.

He laments how Munsiyari, home to the Bhotiya tribe in Johar valley, has transformed "from a pristine, untouched place of great natural beauty into a commercialised place where you go and eat momos and thukpa”.

While Pant draws attention to the alienation of the younger generation from their cultural roots, he also cautions against forcing people back “when there is no livelihood, no medical care, no schooling, not even housing".

Negi ominously warns, "Ye rukne wala nahi hai abhi (this exodus is not going to stop anytime soon)" – unless there are concerted, coordinated efforts to build opportunities that resonate with the aspirations of the youth.

Why the hills are falling silent

| Reasons of migration (in %) | |

| | |

| Livelihood or unemployment issue | 50.16 |

| Lack of medical facilities | 8.83 |

| Lack of educational facilities | 15.21 |

| Lack of Infrastructure ( Facilities like Road, water, electricity etc.) | 3.74 |

| Lack of productivity or yield in agricultural land | 5.44 |

| Migration under the influence of family and relatives | 2.52 |

| Due to damage caused to agriculture by wild animals | 5.61 |

| Other important reason | 8.48 |

Source: Interim Report on the status of Migration in Gram Panchayats of Uttarakhand, Migration Commission (April, 2018)

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your 5 favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)