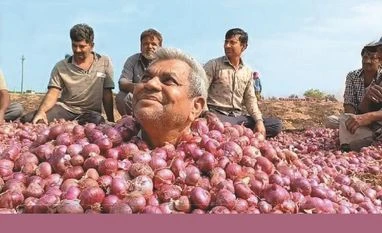

A few days ago, some farmers of Maharashtra buried themselves neck deep in pits filled with onions to protest against the sharp drop in the vegetable’s prices — the result of an export ban, hefty import duty, minimum export price (MEP), and a surge in new crop arrivals. Far away, reports said, consumers in Bangladesh and Nepal, both major buyers of Indian onion, are struggling with sky-high prices.

Onion prices have always been a hot topic and have on occasion been a critical factor in elections. They tend to fluctuate wildly because of limited centres of production, wide and growing consumption, and, most importantly, limited modern processing and storage facilities. So, when prices are down, as they are now, onion farmers prefer to let their produce rot, instead of storing or processing them.

In 2023-24 (FY24), itself, consumer price inflation in onion moved from a negative 16 per cent in April to a positive 86.5 per cent in November 2023. Inflation is measured as a year-on-year increase in prices.

However, from November 1 to December 20, daily data showed that onion wholesale prices in Lasalgaon and Pipalgaon markets (the two major mandis for the crop) dropped by almost 37 per cent and 55 per cent respectively, triggering the neck-deep protests.

A few months ago, when prices had touched rock bottom before it zoomed, the government said in a statement that onion storage was challenging, as most of the stock was stored in open ventilated structures (chawl) in open fields. “Therefore, there is a need for scientific cold chain storage, which is under trial for the longer shelf life of onions. The success of such models will help in avoiding price jerks as witnessed recently,” the statement had said.

Improper storage also means that every year anything between 25 and 40 per cent of the onion produce goes waste. With just 60 to 75 per cent of the produce available for consumption, volatility in prices is a given.

Onions also suffer from low price elasticity to demand. According to an National Council of Applied Economic Research report, price elasticity of demand for onion is as low as 0.1, implying that a 10 per cent increase in price can result in only a 1 per cent decline in demand.

This also implies that a 10 per cent shortfall in supply causes a 100 per cent increase in price, and the reverse could also be true, when supplies rise, as has been the case in the current price drop.

Scorching pace

India’s onion produce rose from below 5.5 million tonnes in FY03 to almost 32 million tonnes in FY23. Seldom has any crop grown at such a pace. Between FY03 and FY13, per capita availability of onion increased more than three-fold from 4 kg to 12.6 kg. An explosion of eating joints and snack corners has led to an increase in consumption, as onion is the main ingredient in spicy dishes.

To stabilise prices, the Centre maintains a buffer stock of onion, which is released whenever prices rise. The buffer size has trebled in the past four years from 100,000 tonnes in FY21 to 300,000 tonnes in FY24.

“The onion buffer has played a key role in ensuring availability of onion to the consumers at affordable prices and in maintaining price stability,” an official said.

In FY24, the buffer is being expanded further to 500,000 tonnes and then to 700,000 tonnes. Of this, till a few days back, 500,000 tonnes had already been procured from farmers.

“Our data shows that prices do remain under check due to the buffer held by the government as traders then know that they cannot act funny,” Consumer Affairs Secretary Rohit Kumar Singh recently said at a press conference. He explained that the ban on exports was necessary, as the kharif onion harvest was expected to be slightly down this year due to delayed planting.

Other major onion producing nations, too, such as Egypt and Turkey, have banned exports, which was putting pressure on the Indian crop. That is why despite the import duty and MEP, some onions still got exported, as there were no other sellers globally.

In November, 120,000 tonnes of onion were exported from India, which, though 29 per cent less than the same month last year, was still on the higher side. In December, in the first seven days, 45,000 tonnes had already been exported.

“The export ban will not affect the farmers and it is a small group of traders who are exploiting the differential between prices in India and Bangladesh markets,” Singh had said.

Some farmers and traders differ.

Supply, shelf life, storage

“The ban would not have had an impact if the new crop wasn’t coming, but with the new crop arrivals trickling in, prices have nosedived,” Surinder Budhiraja, a trader from Delhi’s Azadpur Mandi, told Business Standard. In the Nasik and Solapur belt, he said, onion arrivals jumped from 40,000-50,000 bags (1 bag=50 kg) to 150,000-200,000 bags in the last few days.

“The new onion is 200-250 gm in size, which is very good quality,” Budhiraja said.

Experts say long-term solutions such as increasing the shelf life through irradiation technologies and converting fresh onions into processed flakes are available but have not been pursued with rigour.

R P Gupta, former chairman of National Horticulture Research and Development Foundation, says the long-term solution could be in increasing the quantum of rabi onion stored in warehouses and expanding the area under kharif onion in non-traditional growing zones, such as Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal, Odisha, Haryana, and Punjab. Even in traditional kharif onion areas, such as Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh, more acreage should be brought under the crop.

“In Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh, annually just around 10,000 and 18,000 hectares are brought under kharif onions, which should be raised,” Gupta told Business Standard.

Thirdly, Gupta says, storable high-yielding varieties of rabi onion should be developed and popularised to enhance the storage period. “This will help in stopping the rotting that sometimes goes up to 30-40 per cent, which is the prime cause of shortage.”

Cold storage for onion, says Gupta, should be done in modern and improved facilities and not the traditional ones, where 80-90 per cent of the crop now gets stored. He said specific types of cold storages only for onion should be built.

It is here that the role of schemes to create modern storages can play a big role.

Modern storage

The government in a recent reply in Parliament said that according to available information, currently there are 8,653 cold storages in the country with the capacity of 39.41 million tonnes. India’s production of all horticulture crops in 2022-23 is estimated to be a record 352 million tonnes. It is here that schemes like “Operation Greens” launched in FY18 along with other similar initiatives can help.

The original Operation Greens had three crops: Tomato, onion, and potato. This was later expanded during the 15th Finance Commission Cycle (2021-26) to include a bunch of other perishable fruits and vegetables as well as shrimp. Under the scheme, according to a Parliament reply last week, 53 projects have been approved across the country for eligible crops in identified production clusters with grants in aid of Rs 634.59 crore for a total project cost of Rs 2,457.49 crore.

Unlock 30+ premium stories daily hand-picked by our editors, across devices on browser and app.

Pick your favourite companies, get a daily email with all news updates on them.

Full access to our intuitive epaper - clip, save, share articles from any device; newspaper archives from 2006.

Preferential invites to Business Standard events.

Curated newsletters on markets, personal finance, policy & politics, start-ups, technology, and more.

)