Luca Dal Monte is eyeing the 1966 Ferrari 275 GTB sitting on the shop floor here at Dominick’s European Car Repair. He has travelled from his home in Milan to promote his latest book, a biography of the car’s namesake, Enzo Ferrari.

The 954-page scholarly tome (over 1,000 pages in Italian) has received rave reviews in Italy since it came out in 2016, and has been optioned for an Italian mini-series. (According to Il Giornale, an Italian-language newspaper based in Milan, the book reads like a novel.) David Bull Publishing recently released an English-language version of the book — Enzo Ferrari: Power, Politics and the Making of an Automotive Empire — in the United States.

Dal Monte, an American-ophile who was the head of Ferrari’s North American press office from 2001 to 2005, wrote the book in Italian and translated it himself into English for an American audience. He met me here at this mecca for Italian cars and their admirers, outside New York City. We’re going for a spirited drive through Westchester County in the limited production 12-cylinder automobile that he’s presently admiring.

The steel grey coupe is a fitting emblem with which to remember Ferrari the man, along with the business he founded almost 70 years ago. Like most Ferraris, the car is stunning and not cheap: It cost $14,000 when it was built more than 50 years ago — about the most you could spend on a car at that time — and might bring as much as $3.5 million from a collector today were it for sale, underscoring one reason Ferrari has been called the world’s most powerful luxury brand.

The company’s success owes everything to its founder, who was born in 1898, and had little formal education. He was inspired to become a racecar driver after seeing Felice Nazzaro win the 1908 Circuito di Bologna. But it wasn’t until after World War II, at the age of 49, that he created his legendary car company.

Also Read

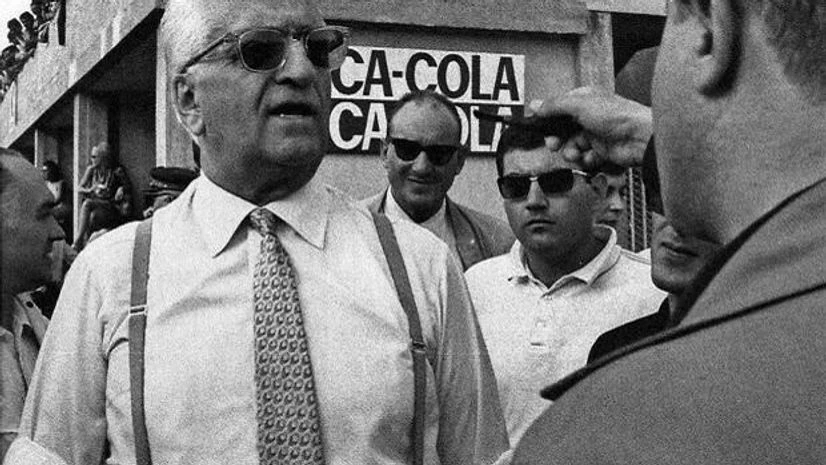

Ferrari is often remembered solely as cold and calculating, with his trademark trench coat and dark sunglasses. But Dal Monte wants readers to see the genius that Ferrari possessed. Yes, he was stubborn, but he was driven and determined to be successful. He used his charm and intelligence to get others to invest in him, said Dal Monte, who saw these qualities in Ferrari’s personal correspondence and his relationship with his sons, Alfredo “Dino,” who died in 1956 at the age of 24 from muscular dystrophy, and Piero, who was born out of wedlock to Ferrari’s longtime mistress, Lina Lardi. (Ferrari’s wife, Laura, suffered severe depression her entire life, and though he had affairs with other women, they remained married until she died in 1978. Ferrari never remarried and died in 1988.)

“In Italy, there was the pope and then there was Enzo,” Dal Monte said as we drove north on New York Route 22, which hugs the state’s border with Connecticut and offers amazing views of the Kensico Reservoir. The GTB’s V12 engine screams with sophisticated mellifluous authority as revs climb, but Dal Monte is used to speaking over mechanical commotion.

“When I was in middle school I became fascinated with Enzo.” He remembers as a teenager in the late 1970s taking an hour-long train ride from his hometown, Cremona, to Modena early one morning with his brother, just to catch a glimpse of Ferrari having his morning shave at a barbershop. Ferrari stared out at them staring in at him, and smiled.

“Even then he was the Grand Old Man, not just of motor racing, but also of the country. You could hear him call in on some of the early TV automotive racing shows and discuss to the point of shouting with the talk show host in order to defend his cars and his drivers — more the cars than the drivers, actually.” What the book doesn’t capture is the circuitous route Dal Monte took going from Cremona to wrangling reporters in America, the world’s largest market for Ferrari, or how he came to write this comprehensive book.

Dal Monte said it all goes back to his second great love (after cars and Ferrari): all things American. When he was a senior in high school, he spent a year as an exchange student in Kentucky and later attended the University of Kentucky, majoring in United States history while writing for the student newspaper, The Kentucky Kernel.

It’s a tall order, but for now, the book stands as the definitive biography of one of the Automobile Age’s most remarkable men. One thing Ferrari understood, Dal Monte concluded, was the value for a luxury brand of keeping its products scarce, or as Ferrari put it in December 1966: “At the end of the year, we will have sold fewer cars than last year, but made more money.” The ever-growing value of the car we’re streaking back down the parkway in underscores the point — one Ferrari’s current caretakers would, Dal Monte said, “do well to remember.”

© 2018 The New York Times

)