Among the 200 objects in The Fabric of India exhibition on display through January at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London is a vast chintz tent used by the renowned 17th-century Deccan ruler Tipu Sultan.

In the late 17th and early 18th centuries, the European craze for such Indian chintz, printed cotton fabric with a glazed finish, prompted several governments to tax and even ban imports.

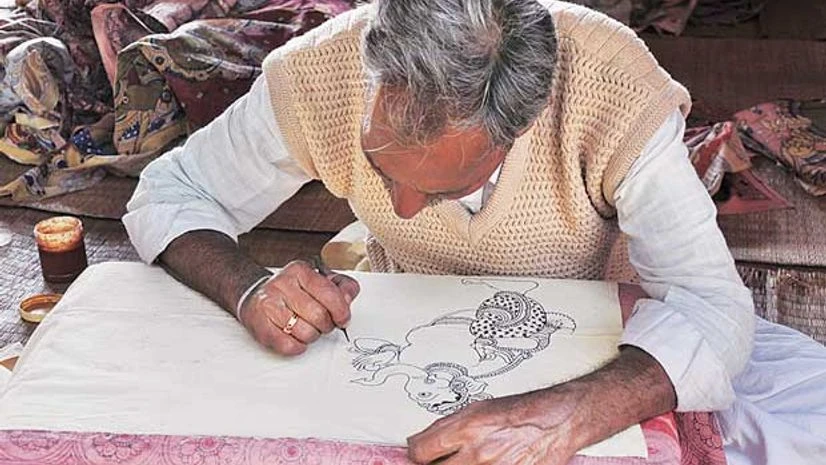

Eventually, Europeans began making the fabric themselves. And the Indian industry declined - its skilled, labour- intensive techniques utilising woodblock printing and meticulous hand painting of floral motifs on unprocessed, hand-dyed cotton, unable to compete with Western manufacturing.

Now, Good Earth, India's most famous home design company, is reviving the production of Kalamkari, as chintz is known in India. (It has already brought attention to other traditional skills such as the creation of Kansa metalware; Naqashi, handpainted papier-mâche and Ajrak, a textile printing technique.)

The company, based in New Delhi and founded by Anita Lal in 1996, is known for drawing on India's rich and varied crafts heritage to create products like tableware and wallpaper, working with several hundred craftspeople in 20 regions. In addition to its online sales, the company has nine stores in India and plans to open two in Turkey by year's end.

"Their products capture everything that is fine and beautiful and delicate about Indian design, both contemporary and historic," says Mark Sebba, a museum trustee and former chief executive of Net-a-Porter, in a telephone interview from London. "I was immediately struck by Good Earth in terms of its ethos and design." (The company is sponsoring the Victoria and Albert exhibition.)

Anita, who is her company's creative director, describes its aesthetic as modern Moghul.

"When I started Good Earth 20 years ago, the National Museum in Delhi had brought the Padshahnama from England to India," she says in a telephone interview, referring to the visual documentation of Emperor Shah Jehan's reign in the mid-1600s. "When I saw the level of refined aesthetics, the delicacy of colour, those resonated with me."

Anita and her daughter Simran Lal, the company's chief executive, are passionate about sustaining Indian crafts. "Today, the Indian consumer is more aware about wanting things that make them proud of where they come from," Simran says in a telephone interview.

Among the company's financial and artistic successes is the Kansa tableware line, Simran says. With roots in fifth-century Ayurveda, the traditional Hindu system of medicine, dishes made of Kansa, an alloy of tin and copper, are believed to help balance the body's PH levels - its acidity or alkalinity. After seeing a Kansa exhibition in Mumbai more than a decade ago, which Anita then bought in its entirety, the Good Earth design team travelled to Odisha, in eastern India, and found a few skilled craftsmen still making the metal ware.

Kansa is labour intensive: molten metal is poured into terracotta molds, then it is repeatedly heated and beaten, eventually producing a lustrous golden bronze- and charcoal-coloured piece.

Good Earth began placing orders for handmade Kansa, updated some designs and now, from the original few workers who were all in one family, it deals with six Kansa workshops in Odisha that support a total of 180 workers. Although machine-made Kansa is readily available, Good Earth sells only the handmade variety, with a 10-inch plate retailing for about $50 (Rs 3,300 approximately).

The Lals hope the chintz will have similar success. Working in the southern coastal town of Machilipatnam, once a thriving port and a centre for dyeing techniques that produced Kalamkari a few centuries ago, Good Earth is collaborating with 95 local artisans to reinvigorate the area's textile heritage.

Good Earth has what it calls a "no rejection" policy, buying every item produced by artisans to ensure them a steady income.

Along with the development of natural dyes using plants, jaggery, or cane sugar, and even iron filings, workers are also testing different motifs for handblock printing on handloomed textiles. Anita notes that each colour application requires a different process and textiles must be washed multiple times for the final colours to emerge.

© 2015 The New York Times

)