Anoopshahr, in the Bulandshahr district of Uttar Pradesh, is all dust and farmland and masculine feudalism. The streets are milling alright, but not with girls. That is, till I reach the gate of the Pardada Pardadi Educational Society where the first sight that greets me is a gaggle of schoolgirls on bicycles.

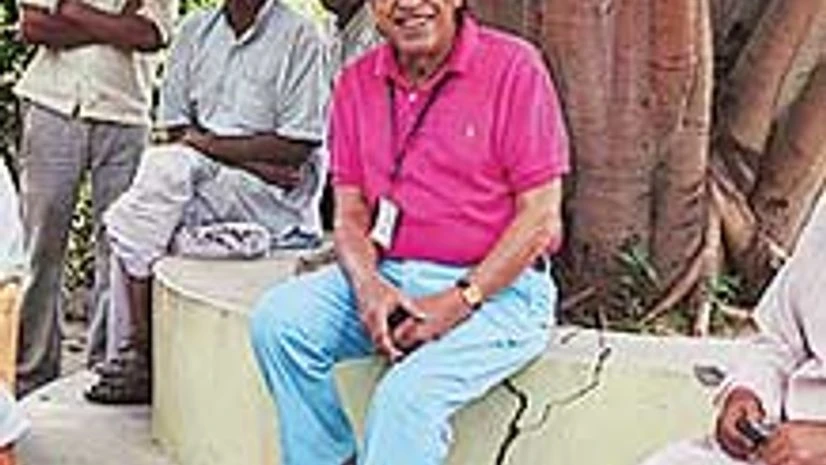

This is Virendra 'Sam' Singh's labour of love - the school he started in November 2000. I run into Singh at the entrance, as it is the start of a new academic year and he is besieged by scores of parents to admit their girls into his school. Wearing cyan blue pants and a pink polo neck with comfortable loafers, the septuagenarian greets everybody with natural courtesy and a bright smile.

Singh lived in the US for 40 years where he worked for DuPont in various leadership roles. There he would often be reminded of the unjust society he'd managed to leave behind. "One day I go to a board meeting and my CEO announces that we should have 30-second silence because in Sam's country 600 people died last night, due to a completely avoidable train accident." At the next board meeting, there will be another round of silence for yet another unnecessary tragedy, and so on, till one day Singh decided to leave his job - he was the South Asia head of DuPont - and come back home to do something about how things are managed, or "mismanaged," here.

More From This Section

After taking voluntary retirement in early-2000, Singh landed up in his hometown and set upon a tall order: to start a school in three months, that too without paying a bribe. People told him it was impossible. It took him four months to start his school but he did it, through an enterprising and unorthodox deal he struck with the principal of the local government school. He got his girls registered with the government school, and since they were all from backward castes the school got to pocket the scholarship fees, while they actually started attending classes at Singh's school. Singh got his permit a few years later, and after paying a mere Rs 21 per student, he managed to acquire the requisite transfer certificates. His school was up and running in November 2000, but on paper it became functional only in 2004. "I had called up my daughter on the first day itself and told her if I happen to die, this is the name of the school and this is the name of the principal, you must admit all these girls there," Singh tells me.

His next hurdle was convincing the parents of the girls to send their daughters to school. He decided that he would systematically target every excuse there is to keep girls at home. The first question he dealt with was the baneful 'how will she get married'? He then decided to offer three meals a day, clothes, books, transport and Rs 10 that would be deposited in the girl's account for every day she attends school. The total amount, approximately Rs 35,000, is redeemable after the girl clears class XII.

The second question was 'what will she do after her studies are completed'? There was no industry here. He decided to start a textile unit, and teach vocational skills. In the morning, students attend regular classes, and in the evening, they learn extra-curricular activities. Singh initially funded the entire process with his own savings, but now gets funding from the Bharti Foundation, Axis Bank, Ernst & Young, among others. Singh has been working on other revenue streams as well. "You have to find other sources to fund the school - it could be textiles, sanitary napkins, agarbattis, call centres - and we are doing all of that." He has faith that one day, the profits from all these, will fund this school and more.

After trudging from village to village, collecting the girls, Singh's school started with 45 girls - and within a week, 31 dropped out for various reasons. "My whole team was very despondent at the time, but I told them to focus on how to make these 14 into 15," says Singh. It now has almost 1,300 girls on its rolls from over 50 villages, and drop-out rates have fallen dramatically to 8-9 per cent, notes Singh.

For most of history, Anonymous was a woman. These words by Virginia Woolf find testament in Singh's family tree, where names spanning eight generations are painted on a wall inside a family compound, if you happened to have been a fortunate male descendant. For some five generations of Singh's Thakur family tree, starting with the very first known ancestor, simply mentions an unknown Shrimati (Mrs.) when it comes to the women in the family. Singh's elder daughter Renu's avowal led to names of some women being added, starting with Singh's generation.

As I go around the school, meeting teachers and volunteers, the girls surprise me with their superb confidence and joie de vivre. A bunch of them awaiting their class XII results are attending an English-training lab in the school to prepare for college. When I start talking to them in Hindi, they insist on speaking English, for you know, "practice." Devyani Chaudhary, 17, tells me "Sam Sir's dream is not just to teach us well, but that after graduating, we shouldn't just sit at home doing housework - instead we should all get jobs and become independent." Chaudhary is going to Bengaluru next month to study for a bachelor's degree in yoga, but her dreams are far bigger. "After this course I will get a job and save money to study law and become a lawyer just like my grandfather," she says with heartening determination.

All 48 girls who have completed class XII are going for some higher studies this year, for the first time in the school's 15 years, and three are going to the US on scholarships.

Deepak Mukarji, an independent consultant who worked for DuPont in the early 90s with Singh, tells me over a phone call: "He would stick out like a sore thumb in the business world, because his first objective was to always find out the people impact of every decision." Singh invites everybody he knows to visit the school, and once they do, they can't help but give out of the goodness of their hearts. Mukarji has sponsored one girl's education at Pardada Pardadi. The school has a baseball team, and Mukarji tells me excitedly how they have played against the American Embassy School kids and beaten them at their own game!

For the grandfather of four, a vacation is just a different activity at a different place. "Last winter I went for a six-week vacation to the south, and visited every college I could there," he says. His most memorable moment during his vacation was finding the Swami Vivekananda University in Bengaluru: "And now 16 of my girls are going there for higher studies this year". The avid reader does not consider himself religious, but has an ongoing deal with his maker: "You do my work [take care of my health] and I'll do yours." At 75, Singh's energy levels are a sheer marvel, as he hops from class to class meeting students and teachers, inquiring about school goings-on.

Singh hopes that perhaps one or both of his daughters would manage the trust after him. Renu, who is settled in the US, is certainly proud of her father's achievements. "He has made all his dreams come true. How many people can say that in their lifetime?" But when it comes to who will continue after him, she says "I don't think one person will be able to take the place of Dad. It's going to be a team effort."

)