It was an inglorious start to a military career. The first shots that John Low's battalion had fired with deadly intent since his arrival in India had been aimed at their mutinous comrades….What came next was, if anything, even more inglorious, still more bizarre, and very nearly as bloody…. Three years later, it was not the Indian sepoys but their European commanders who mutinied almost to a man.

Out of 1,300 officers commanding native troops in the Madras Presidency, 90 per cent refused to obey the orders of their superior officers. Only 150, most of them lieutenant-colonels and above, signed the test of loyalty imposed by the Governor, Sir George Barlow. The rest locked up their colonels, broke open the nearest Treasury and took out thousands of pagodas to pay their native troops, whom they then marched off wherever the fancy took them. From the beginning of July to the middle of September 1809, the whole of southern India was in a state of lawlessness ….

Never before and never since had a mutiny by British officers swept through an entire army. The mutiny of the Madras Officers in 1809 remains a unique event. Yet the affair has remained strangely obscured, glossed over if not actually omitted in most histories of the British Empire and the Indian Army. …

So why was there a White Mutiny? Why on earth did the handpicked guardians of the new master race in India turn on their commanders and plunge the bottom half of the country into giddy internal strife?

There were not one but two British armies in India. There was the King's Army, those of His Majesty's Regiments which had been seconded to India for a period …. And then there was the army of the East India Company, which was raised in India, trained in India, fought in India….In all three British regions, or Presidencies as they were called - Madras, Bombay and Bengal - not only did the Company's Army soon come to outnumber the King's Regiments, the Company's Army was soon predominantly made up of Indian troops.

British rule depended on the fidelity of the sepoys, and on that alone. And that fidelity could be earned and kept only if the British officers who commanded the native regiments were up to the job. …On the European side, the growing corps of young British officers in the native infantry and cavalry were growing disillusioned. … Most of them arrived in India without a penny and soon fell into debt. A subaltern on arrival had to find between 1,500 and 1,800 rupees for equipment and uniform. He would need to borrow this money and then insure his life as security for the debt. Even if he did not drink or gamble, his debt was likely to have doubled by the time he became a captain, up to six or seven thousand rupees -£35-40,000 in today's money. He was unlikely to be able to clear his debts until and unless he became a major, which might be years off, because promotion was so slow….

Grimmer still, an officer who joined the Company's Army at the end of the eighteenth century had little reason to hope that he would ever see England or his family again. The annual returns of the Bengal Army showed that between 1796 and 1820 only 201 officers lived to retire to Europe on pension, while 1,243 were killed or died on service….

The officers of the Coast Army had another source of grievance, too.… The officers of Bombay and Bengal were entitled to higher pay and allowances.

From the beginning of 1807, if not from an earlier date, a spirit of discontent was fermenting among the Madras officers. … The first reform that tickled up the existing resentments was the affair of the bazaar duties. From time immemorial… officers commanding districts and stations all over India had been entitled to take a cut on the goods sold in the military bazaars which straggled along the back of cantonments, where everybody did their shopping. This had been a nice earner to supplement those wretched salaries.

The Court now pronounced that levying such duties was contrary to the Articles of War and 'has an evident tendency to make the soldiers discontented with their officers, by feeling themselves taxed for the benefit of those who command them'. Worse still, 'the amount of the collections in military bazaars has always depended, principally, on the extension of spirituous liquors to the troops.' Not only were the officers exploiting the poor sepoys and their families, they were encouraging them to drink - something which particularly horrified the Court, where strong Evangelical tendencies were taking hold. …In July 1807, the bazaar duties were duly abolished.

The next scam to be tidied up… was the so-called 'tent contract'…. Under the existing system, which was only five years old (it had begun in 1802), the CO of a regiment held the contract for everything required to fit it out for movement in the field - tents, carts, bullocks, drivers and labourers etc.…[I]n May 1808 (these things always took time) the tent contract, too, was abolished.

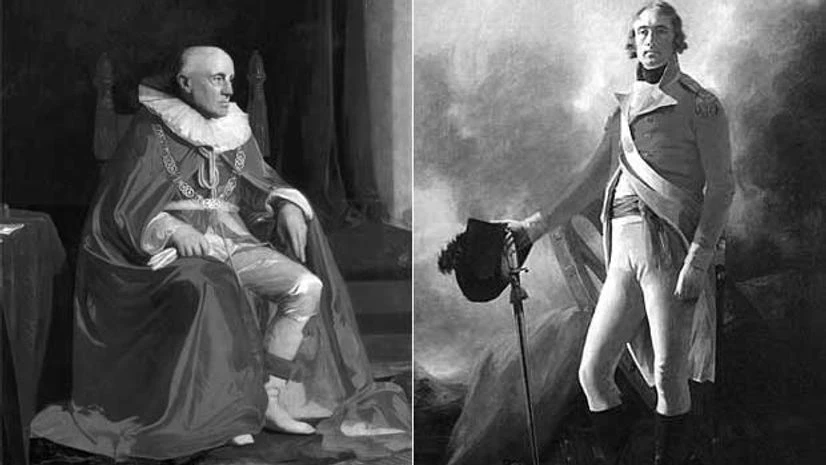

By now [Lieutenant-General] Hay Macdowall was in post, and he was already in a steaming rage. What had first detonated his umbrage was…characteristically, a question of his own pay and perquisites. Previous Commanders-in-Chief had always enjoyed an ex officio seat on the Governor's Council, with a handsome additional allowance to go with it. But Bentinck… appealed to the Court of Directors to curb the excessive power of the military in India. The Court had responded by removing the C-in-C's automatic right to a seat in Council.

When he found out, [Macdowell] …soon gathered a noisy and indignant following throughout the Coast Army for his campaign against what he called 'these disgusting measures'. On Christmas Eve, he reviewed the Madras European regiment at Masulipatam. He told them that they had been overlooked and neglected in their remote station. ….

Then he took ship for England, firing off reprimands and protests in all directions. …Instead of pausing to reflect that his greatest enemy had now disappeared from the scene and it might be possible to begin mending his fences with the Army, Sir George in his feverish pet cast around for someone else to punish. Major Thomas Boles was the Deputy Adjutant-General. His signature appeared on Macdowall's parting sally, but only as a formality because all such orders had to be transmitted through the Adjutant…. Barlow suspended both Boles and Capper….

Not unnaturally, Major Boles protested that he had done nothing wrong and refused to apologize. In no time, yet another petition was circulating through the cantonments, this time addressed to the Governor-General in Calcutta, demanding that Barlow be sacked….

But …on May 1, 1809, [Barlow] had half a dozen colonels and another half-dozen majors and captains suspended or removed from their commands.

Finally, provoked and inflamed, the officers of the Madras Army broke into open mutiny. … The first outbreak took place within a European regiment, the first division Madras, which was stationed at Masulipatam. These were the very men to whom Hay Macdowall had delivered his inflammatory farewell address on Christmas Eve …. Macdowall's remarks could not help having an impact, and the new commanding officer had been warned to expect trouble. Colonel James Innes, well-known to be not the sharpest knife in the box, arrived in a mood to detect 'sedition in every word and mutiny in every gesture'. …

By sheer bad luck, at this very moment, Admiral Drury, the naval commander at Madras, ran short of European troops to serve as marines on his coast squadron. Under recent regulations, King's soldiers were no longer to be detached for such purposes except in an emergency, which this was not, so the Government lighted on the 1st Madras European regiment to fill the complement that Drury desired - 100 men and three officers. This was the last thing anyone in Masulipatam wanted, service at sea being even more dangerous and unhealthy than service on land… A deputation of officers went to Innes and begged Innes to suspend the embarkation until they had referred their protest to HQ. No dice. …

Tumult broke out across the barracks. Major Joseph Storey of the 1st/19th Native Infantry, the officer next in seniority to the Colonel, led a posse to Innes's bungalow, demanding he recall his orders. Innes refused… The men were with Storey. Innes was confined in his bungalow under armed guard. The embarkation orders were cancelled. Major Storey wrote to Madras explaining what he had done. He also wrote urgent messages to the disaffected officers in other garrisons, appealing for their support. Joseph Storey was the first white mutineer.

The officers at Masulipatam had formed a committee. So had the officers at most other stations in the Coast Army. These committees now began to pledge each other to support their brother officers to the last drop of their blood. At Secunderabad, Jalna and Ellore, plans were speedily formed to march to the aid of the Masulipatam officers, if they were attacked by Government forces….

The next move for the more determined mutineers was to march off and join forces with other rebellious garrisons. They needed to pay and feed their sepoys to keep them loyal. So in station after station the mutineer officers took to armed robbery. They went to the nearest Treasury, overpowered the guards, broke open the chests and took whatever they found inside.

Upon the scene now comes Lieutenant-Colonel Samuel Gibbs of HM 59th Regiment. … [He] ordered his Dragoons to attack the startled sepoys from Chittledroog.…The official tally was nine dead and 281 missing…. A realistic estimate might be around 300 dead. The British had no casualties to speak of….

So the great White Mutiny came to its inglorious end. And several hundred sepoys lay dead in the ditches of Seringapatam, gunned down by Dragoons who were supposed to be their comrades-in-arms. The sepoys had never had any quarrel with the Honourable Company. In marching, they were simply obeying the commands of their discontented officers.

Excerpted with permission from Simon and Schuster India

)