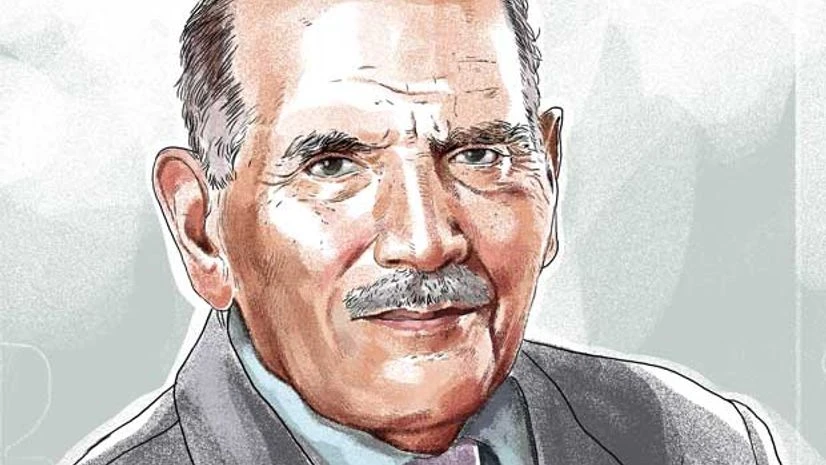

Padma Bhushan Faqir Chand Kohli, father of the Indian software sector, turned 90 on February 28, 2014. Millions who join the Indian information technology (IT) sector every year should celebrate this day, because had it not been for him, the sector would not have reached where it is today. Kohli, however, does not believe in sitting on laurels. He feels though software will continue to do well, local language computing needs attention.

"IT is not just about software, it is about hardware, too. Add to this that software has to be in all languages, not just English. Since we have been focused on exports, we have capitalised on the English language. But there is no or very little software that caters to the needs of the 800 million Indians who do not speak English," he tells the Business Standard. Kohli attends office regularly even now.

He believes like China introduced Mandarin computers and Saudi Arabia Arabic language machines, India too needs to provide computers to 800 million people in 22 languages. "We have been creating software for the world, but will it make any difference for our country? No," he says.

Also Read

Kohli is best known as the first chief executive of India's largest IT services company, Tata Consultancy Services (TCS). His contributions to the growth of the Indian technology sector are many. A master in electrical engineering from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Kohli is a pioneer and a visionary.

Even before taking over as the boss of TCS, Kohli was using technology to solve problems for the Indian power sector. In the mid-1960s, and as part of Tata Electric Companies, he was the architect of the computerisation of the power grid that serves Mumbai. His association with Tata Electric for almost two decades saw Kohli being nominated as director of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineering (IEEE) in the US in 1973.

In September 1969, he became the general manager of TCS, and in 1974 director-in-charge. He recalls that neither the Indira Gandhi government nor the governments under Morarji Desai or Charan Singh had any room for computers.

His regular trips to the US as part of the IEEE brought him in touch with Burroughs, a computer manufacturer from Detroit. Kohli says Burroughs agreed to give some work to TCS. Burroughs wanted a health care software package that would be packaged with their computers. "We managed to deliver the software and there was no looking back. That was the end of 1974," says Kohli.

Born and raised in Peshawar, Kohli majored in physics from Punjab University. He went on to do his bachelor's in electrical engineering from Queen's University in 1946 and also worked for a year at the Canadian General Electric Company. From there, he headed to Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) to do his master's. In 1951, Kohli joined Ebasco International Corporation, New York; Connecticut Valley Power Exchange, Hartford; and New England Power System, Boston, for training in power systems operation. In August 1951, he returned to India and joined Tata Electric.

Kohli, though remembered for his work in software, has been active in education. In 1959, when P K Kelkar became the founding director of the Indian Institute of Technology, Kanpur, he got Kohli to join the faculty recruitment committee. Kohli is also responsible for the turnaround of the College of Engineering at Pune, the third oldest technical institute in Asia. Started in 1854, the institute had only its history to cherish. Kohli not only pushed the Maharashtra government to make the institute autonomous, but also set a road map for the college to regain its lost glory.

The one thing bothering Kohli now is the local-language computing riddle. "Two or three years ago, I found a huge backlog of legal work in translation in Indian courts. Lower courts in India generally use local languages, but when these cases go to higher courts, they need to be translated. When I asked one of the officials where are the translators, I was aghast to find that all translators were trained in English to Marathi or English to Gujarati, but nothing was used to train in reverse," he said.

Kohli's complaint is none of the governments has given enough thought to this problem.

)