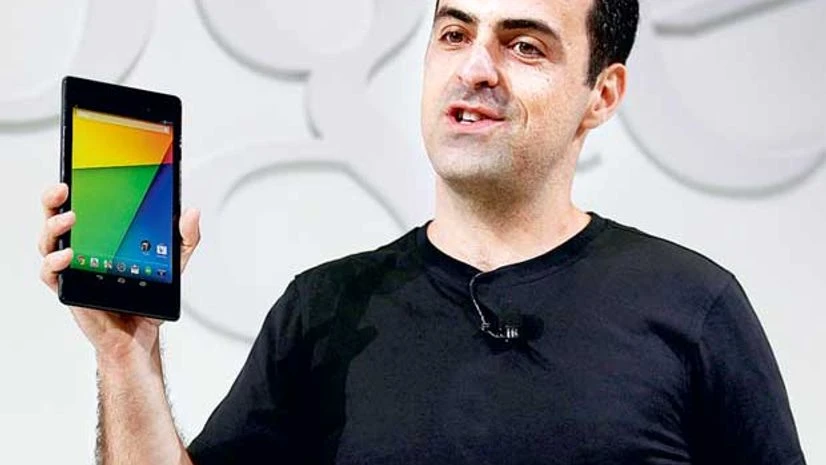

Xiaomi executed a major coup in August 2013 when it hired Hugo Barra, one of Google's top Android executives, to be its global vice-president. He made it clear that Xiaomi's primary targets were not the affluent countries of the West, but "places like India, Russia, Indonesia, Latin America, Thailand … where the equation of quality and affordability works, because it's in those markets you can replicate what the company has done in China." "This [India] is a very large country with a very young population that's quite tech savvy," said Barra in January at the Delhi launch of a new model, the Mi 4. To this population, the "mobile phone is the gateway to the world," he said. "It's an incredible opportunity."

Today, according to Manu Jain, Xiaomi's India head, Xiaomi sells between 50,000 and 100,000 phones in India every week. The company initially shipped its stock to India on numerous flights, but now relies on its own chartered aircraft.

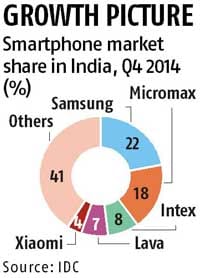

Despite its successes in India, Xiaomi has a long way to go to catch up with market leaders, including Samsung and Micromax: market research by a Hong Kong firm, Counterpoint, found that for the third quarter of 2014, Samsung commanded a market share of 25 per cent, and Micromax, 20 per cent, while Xiaomi, "with just two months of sales," had won a market share of 1.5 per cent. Jain says Xiaomi isn't focusing on taking on the current market giants. "We don't look at market shares or compete with any other brand," he says. Barra, too, insisted the company wasn't focusing on garnering market share. "It's about building an engaged user base," he said.

As the market for smartphones grew in India, the higher-end smartphone brands primarily relied on chips from the American manufacturer, Qualcomm, while Indian companies were quick to collaborate with Chinese companies who were making significantly cheaper smartphones. Most Chinese manufacturers also allowed importers to mix and match components, and thus create a range of models to appeal to a variety of consumers-particularly useful in a heterogeneous market like India.

The China advantage

The rewards of tying up with Chinese manufacturers were quickly apparent. In 2012, Micromax broke into the ranks of the top five smartphone sellers in India. By the first quarter of 2013, Micromax and Karbonn were the second- and third-highest selling smartphone brands in India, behind the market leader, Samsung. IDC announced that in the second quarter of 2014, with Lava joining the list, Indian companies accounted for three of the top five smartphone sellers in the country. This February, Canalys, a Singapore-based research firm, reported that Micromax had dethroned Samsung as the highest selling smartphone brand in India-a claim that Samsung has disputed.

Xiaomi has positioned itself to appeal to users of high-end phones while offering them significantly lower prices than the competition. The company's pricing has always been at odds with standard industry strategy. "Typically, all consumer-electronics products have the maximum margins when they are launched," Rajat Agrawal, the editor of the technology news portal BGR India, says. "Companies usually take advantage of it being the latest and greatest product the world has ever seen, and pile on their margins as well as marketing and other overheads while pricing a new product." Xiaomi follows the reverse strategy, offering new products with very low margins, and focusing on increasing revenues as the product stays in the market.

But while Xiaomi is benefitting from aggressive pricing and smart marketing in India, it is also facing conflicts over intellectual property. This is part of a larger trend of legal battles between technology companies around the world, involving major players such as Apple and Nokia. Rushabh Doshi, an analyst at the research firm Canalys, says that "due to their recent arrival into the mobile market, and also due to minimal investment into R&D, new entrants could fall victim to IP infringement of older companies like Nokia or Ericsson."

In December last year, Swedish telecommunications company Ericsson filed a lawsuit against Xiaomi in Delhi, alleging that the Chinese firm was infringing on its patents. On December 8, after examining the complaint, the Delhi High Court ordered Xiaomi to stop sales in the country until February 5, when the next hearing was scheduled. After Xiaomi appealed the December 8 order, a division bench granted it permission to import and sell phones that had Qualcomm processors, but not those that had chips from China's MediaTek. The case comes up for hearing again on March 18.

Agrawal believes that negotiating the patent regime will present a challenge to Xiaomi, "especially when it attempts to grow outside of China." But its rapid global success could also give it an advantage in this regard. "With its current valuation of about $45 billion, and a looming IPO in the next couple of years, which could theoretically value the company at $100 billion, Xiaomi could also look at buying patents to protect itself," he says. The legal dust-up should serve as a note of caution to smartphone companies trying to take advantage of the growing Indian market, according to Doshi. "It should give all smartphone companies in India, whether local or international, a wake-up call to ramp up their own patent portfolios, which can be used as bargaining chips in such injunctions."

Barra says that Xiaomi wanted "to build an Indian business and an Indian company. Manufacturing is in that spectrum and something we'd like to do." While he didn't commit to a timeline, he expects the process to start within a couple of years. Xiaomi joins a string of companies that have indicated an interest in producing smartphones in India. Some have already taken steps in this direction. Micromax, which was already making tablets in a facility in Rudraprayag, Uttarakhand, announced in April last year that it had also started making smartphones there.

Make in India dream

Some of these plans dovetail neatly with Prime Minister Narendra Modi's "Make in India" campaign, through which the government aims to attract investment in manufacturing centres in India. It appeared plausible that, in the natural course of events, we would soon see smartphones entirely manufactured in India, helped along by friendly government policies. But some industry leaders have also expressed uncertainty over setting up manufacturing here. Barra says, "It's not just about finding a factory in India. It's about having an ecosystem in place so we can source locally." Sudhir Hasija, the chairman of Karbonn, echoed this concern. "The most unfortunate part is that the supply chain is not in India," he says. "There are minimum 127 to 147 components in a phone. If one screw is missing, my entire production line is stopped." He adds that the immediate disadvantages of setting up a plant in India could be considerable. "My costs will go up, balance sheet dynamics will go up," he says.

Most smartphone facilities currently in operation in India are assembly centres, where workers put together components that have been fabricated outside the country. The capacity of Indian plants to manufacture smartphone components from raw material remains limited. If India is to transform into a global investment destination, like China, it will need to develop an ability in primary manufacturing, where industrial materials are created from raw materials.

As with companies in most other sectors, smartphone brands, too, are watching to see what incentives the government will propose under the Make in India initiative. Favourable policies may lead many who have currently expressed interest in setting up facilities in India, such as Karbonn and Xiaomi, to do so. But the prospect of a smartphone that is entirely, or even significantly, manufactured in India, remains a distant one. In the immediate future, we may see an increase in the number of smartphones sold in the Indian market that are also assembled in India, but most will continue to be "Made in China."

This is an extract reprinted with permission from The Caravan, March 2015 © Delhi Press.

www.caravanmagazine.in

)