He is Marwari, was born and brought up in Patna, got started in business in Mumbai, now lives in London's stylish Mayfair and is fabulously rich: his net worth is $3.5 billion. These days he feels inspired by the public works funded by Andrew Carnegie and David Rockefeller. Anil Agarwal, the 60-year-old chairman of London-headquartered Vedanta Resources, wants to be counted amongst the world's top philanthropists. In September, Agarwal announced that he would give away 75 per cent of his wealth to charity. He said he took the decision after a meeting with Bill Gates, the world's second-richest man who has committed a large part of his estate to the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. However, Agarwal does not yet feature in the list of billionaires who have signed The Giving Pledge started by Gates along with Warren Buffett.

Still, this is easily the largest commitment to charity by any Indian businessman. Agarwal's various companies in India in 2013-14 spent Rs 300 crore on corporate social responsibility, or about 3 per cent of their combined net profit, which is above the mandatory 2 per cent. In addition, there is Vedanta Foundation, the NGO he set up in 1992, that works in the fields of education, nutrition and livelihood. Agarwal now wants to expand the scale of his philanthropy.

Those who fear that Agarwal will sell three-fourths of his stake of almost 70 per cent in Vedanta Resources to help the poor and the needy, and in the process dilute his control over the natural resources company, need not worry. What he plans to do is place these shares in a trust which, he expects, will earn dividend income of up to Rs 5,000 crore over the next five years. This money will fund his philanthropic work. For this purpose, he has set up the Anil Agarwal Foundation. In October, the foundation put out a newspaper advertisement for a vice-chairman & CEO. Over a hundred applications were received, Agarwal claims, and the applicants include bankers, CEOs and bureaucrats.

The blueprint for the foundation will emerge once the CEO takes charge. At the moment, Agarwal has identified three areas in which he wants it to work: child development, women empowerment and education. His family is on board with the decision. The rest of the stake will yield enough for his family, Agarwal insists. It will still be bountiful, for sure: if 75 per cent can yield dividend income of up to Rs 1,000 crore a year, the remaining will fetch him over Rs 300 crore.. Agarwal says that in a couple of years, he hopes to devote a lot more time to the foundation than to his business. Tom Albanese, the former chief executive of Rio Tinto, joined Vedanta Resources as CEO last year in New Delhi. His kids have not made up their mind whether to join the family business or not: while his son, Agnivesh, is involved with the precious metal business of the group, his daughter, Priya, was in the communication industry.

A sizeable chunk of the budget of the Anil Agarwal Foundation will be spent in India - the rest in Africa. The commitment from Agarwal comes at a time when his various businesses in India have faced one roadblock or the other. His iron ore business was hit after the Supreme Court banned mining in Karnataka and Goa over allegations of impropriety in the sector. Mining has restarted in the two states but the volumes are low. The contract for his oilfields in Rajasthan expires in 2020, and there have been reports that the government may renew it but after tinkering with the terms. His alumina refinery at Lanjigarh is functioning at 25 per cent capacity after it was denied bauxite from the Niyamgiri hills. The Odisha government hasn't agreed to Agarwal's pleas for new mines so far. (Between the Lanjigarh refinery and an aluminium smelter at Jharsuguda, Agarwal has invested Rs 60,000 crore in Odisha.)

Though his business projections may have gone awry, Agarwal denies he has fallen victim to political or corporate rivalry. "They (the Odisha government) brought me here as a bride. How they treat me here, good or bad, depends on them," Agarwal likes to say. He has met Finance Minister Arun Jaitley and Prime Minister Narendra Modi and finds the latter's enthusiasm for more industry welcome. In spite of his offer to buy the residual stake in Hindustan Zinc as well as Balco from the government having lapsed (he can purchase the shares in the proposed open auction), he is willing to acquire more public-sector units whenever they are put on the block. If there is bitterness inside, none shows on Agarwal's face. When we meet at the Lutyens Suite at The Oberoi in New Delhi, the television in front of him plays images of industrialist Gautam Adani in Australia along with Modi, and the anchor announces that State Bank of India has agreed to lend $1 billion to Adani for a mining project in that country. Agarwal laughs inscrutably. I can't tell if he is happy that this is a business-friendly government or if he is miffed at the special treatment given to the Gujarati billionaire.

Agarwal's patience is elephantine: many others have exited India on facing lesser problems. Is big-ticket philanthropy Agarwal's way of winning over public opinion? Agarwal, a Krishna devotee, says what motivates him is Dharma. "It always talks about what you can give back." In four to five years, he wants to create a business that is robust; part of the returns will go to the society and the rest to the family.

At the top of Agarwal's current philanthropic agenda is a city built around a university, like Boston. In fact, he had announced such a project, to be located near Puri, more than eight years ago. Such was the buzz that at a conference to announce the MoU for Vedanta University, Chief Minister Naveen Patnaik, who seldom talks to the media, was seen eagerly fielding questions, even those directed at Agarwal. However, the Lokpal, in its March 2010 report, said the MoU was not a legally enforceable contract. The Orissa High Court in November 2010 declared the land acquisition null and void. The state government and the company have moved the Supreme Court against that order. Out of the 6,138 acres required for the project, 3,495 acres of private land were acquired, while the government had leased 509 acres to the university. This land is lying abandoned and squatters have moved in. But Agarwal is hopeful the matter will get resolved soon. His executives too say that after a few years of inaction, talk of the university has started doing the rounds once again.

Will Odisha co-operate? It had rolled out the red carpet for Agarwal when he came up with the proposal to set up the alumina/aluminium business in the state. It didn't mind sending the forest diversion proposal for the Lanjigarh refinery to the Centre on a Sunday, a gesture often cited by the project's critics to highlight the bonhomie shared by the businessman and the Patnaik government. But the relations have turned lukewarm after the Niyamgiri episode. Afraid of criticism from green activists and political rivals, the Patnaik government is now seen offering just lip service to Agarwal.

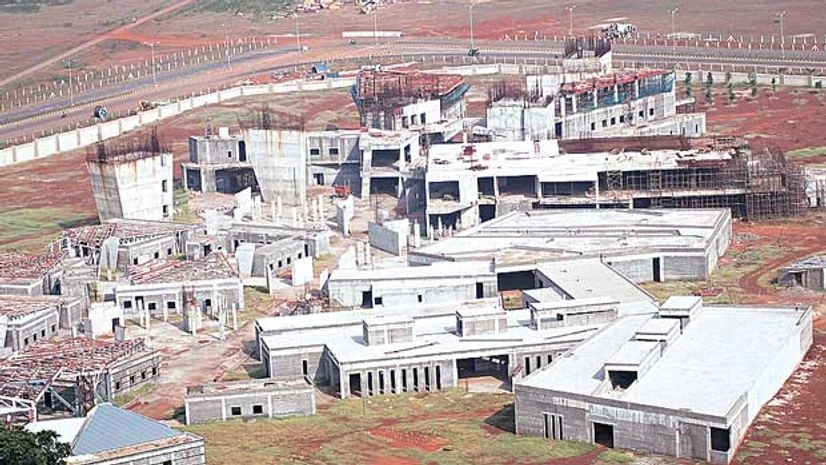

The Vedanta Cancer and Research Centre in Chhattisgarh wears a deserted look, though half the construction is complete

The hospital was launched with fanfare over five years ago. For Rs 1, the state government had allotted 20.15 hectares to Vedanta Foundation for 30 years. When the Naya Raipur Development Authority and Vedanta Foundation signed the MoU in September 2009, it was announced the project would be completed in three years. A year ago, the authority asked the foundation to explain the delay. According to its CEO, Amit Kataria, the state had raised the issue with Agarwal during his visit last month, and he promised to complete it soon.

Agarwal's critics point out that he has committed to large charitable projects in states where he has substantial interests and has ignored his own state, Bihar. Agarwal says he had big investment plans for Bihar but the state lost all its mines to Jharkhand, which was carved out of Bihar in 2000. If Bihar gets the "special category" status that it has been pleading for, Agarwal says it will be his topmost priority to set up a unit there, and he will focus on health and education. In 2012, he had offered to set up a world-class university in the state but there has not been much progress on the ground.

Till that happens, Agarwal could start with Miller School in Patna, his alma mater, now called Devipad Chowdhary Ucch Vidyalaya.The yellow paint on the walls looks as ancient as the colonial building. It is in dire need of repair. The school has one of the largest playgrounds in Patna, but it is frequently used for political rallies, marriage ceremonies or other commercial purposes. Some students remember Agarwal as the middle-aged "Uncle" who gave them HMT watches and school bags two years ago. The teachers don't know a thing about Vedanta Resources but clearly remember the promise Agarwal made to renovate the ramshackle building. The offer, Agarwal's friends say, got entangled in red tape. But the teachers were mesmerised. "He is just like you and me," gushes Sushil Kumar Sinha who teaches mathematics. "We knew that he was a very rich man and lived in London, but here he came as a former student. He sat on the ground while conversing with our students." The thousand or so students of the school come from socially and economically backward sections. Most are dressed in a light blue shirt, navy blue trousers and rubber slippers. Many drop out after Class X.

That is nothing new: Agarwal too had left Miller School after matriculation to follow his father in their scrap business. He found Patna too small for his ambitions. In 1975, he came to Mumbai and never went back. But the old bonds remain intact. P K Agarwal, president of the Bihar Chamber of Commerce and Industries, says: "When he is in Bihar, he speaks a like a Bihari. He has deep love for Patna." A couple of years ago, ISKCON asked Agarwal for support in the construction of a temple in Patna. He readily agreed and offered Rs 1 crore, according to Agarwal. There could be more of that in the days to come - Agarwal is, after all, on a mission.

Additional contribution with Satyavrat Mishra and R Krishna Das

)