On 27 May, analysts tracking Coal India Ltd (CIL), the world's largest coal producer, got the shock of their lives: India's monopoly coal producer had posted an 18 per cent jump in net profit for the year ended March 2013.

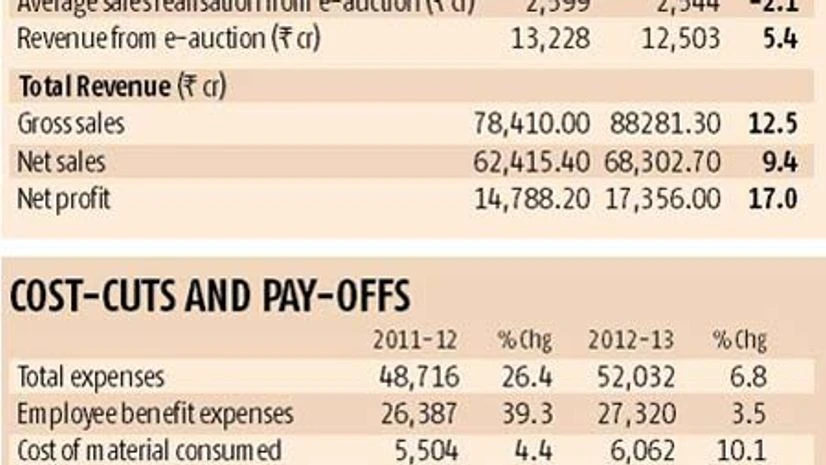

This increase in profit came even as its production, after remaining stagnant for two successive years at the back of delayed clearances, had shown a minor 3.7 per cent rise; the company had not been allowed to raise prices since two years; its traditional profit centre of e-auction had performed badly with spot sales dipping both in volume and value terms for the first time in eight years; and the growth in cash balance, another major contributor to revenues through interest income, had taken a significant beating. To add to the mystery, the entire incremental output of 32 million tonnes in 2012-13 had been channelised towards power companies which buy low-grade coal at cheaper rates. But the company still reported a net profit of Rs 17,356 crore. And that too after contributing Rs 35,800 crore, roughly a half of total sales, to the exchequer-both the Centre and the state governments'-in the form of royalty and cess on coal and a slew of other taxes and duties. So, what explains the magical growth in profits for CIL-the Maharatna public sector unit which alone meets over a half of the commercial energy demand of the third-largest economy in Asia?

A Business Standard analysis of the operational and financial performance of the BSE-listed company reveals how the miner brought about a crackdown on expenditure and a selective push to high-margin sales to garner profits. Coal India's overall expenditure had grown 26 per cent in 2011-12 to Rs 48,716 crore. In 2012-13, the growth came down to 6.8 per cent (total expenditure for the year stood at Rs 52,032 crore). This was largely the result of a massive decline in employee cost which alone accounts for over a half of the company's total annual expenditure. The growth in spending on account of employee benefits, including salaries and wages for its 383,000-strong workforce, came down from 39.2 per cent in 2011-12 to as low as 3.5 per cent in 2012-13. Employee cost grew from Rs 18,931 crore in 2010-11 to Rs 26,387 crore in 2011-12 and further to Rs 27,320 crore last fiscal.

CIL Chairman S Naarsing Rao attributed the trend to the fact that 2011-12 was the first year when new wages, under the fifth round of the Joint Bipartite Consultative Committee (JBC) discussions, became applicable for the company's workforce. "Post the negotiations with workers, the new wages became applicable beginning July 2011. So, while the impact was felt only for nine months in 2011-12, it pushed employee expenses by 25 per cent," he told Business Standard. The state-owned miner is India's largest listed employer. Wages are revised every five years after multiple rounds of discussion in the JBCC.

Trimming costs

The huge expenditure cut was brought about also by pulling down spending on overburden removal. Overburden is the layer of earth above the coal seams which has to be dug out first before mining coal. Removing less overburden hampers future output. And yet the overburden removal expenditure, which had increased 41 per cent in 2011-12 to Rs 3,696 crore, actually declined 13 per cent to Rs 3,201 crore in 2012-13. A senior CIL official confirms the company spent comparatively less on overburden removal last year but says spending under the head is a function of project mix.

In order to keep profits intact, the company also maximised earnings from sales of high-grade coal which fetch higher costs per unit cost of production. High calorific value coal corresponds to the top six of the 17 quality bands in the current gross calorific value system representing CIL's output. The six bands together constitute around 30 per cent of the total 452 million tonne production and are sold largely to cement and sponge iron companies.

CIL supplies coal to non-power consumers at a 30 per cent higher price than power companies. The miner's average realisation from non-power category stood at Rs 1,450 per tonne last year as compared to Rs 1,150 per tonne realisation from power consumers.

The extent of profitability accrued from higher grade sales can be gauged by the fact that CIL had to recently slash prices of higher grades of coal by as much as 10 per cent after consumers refused to buy, alleging prices had surpassed even the prevailing global rates.

Getting the right mix

"The main reason for our profitability last financial year was grade mix. The price variation between lower and higher calorific value coal was very high last financial year. We sold more of high quality coal. This is why the average realisation increased to Rs 1,472 per tonne by the end of 2012-13," Rao says.

Another part of the profit earning strategy deals with outsourcing works contributing to as much as 40 per cent of the total production cost for CIL. The miner reduced dependence on its own less efficient workforce and fetched more output per unit cost by roping in more efficient private parties to do the job. Mostly work related to overburden removal, certain parts of production and transportation was outsourced to private companies willing to deliver at a pre-determined price. Private companies have a high equipment utilisation rate and do not have to follow the time consuming government procedure for procuring goods and services.

However, the success of the multi-pronged strategy was marred by a sharp rise in the expenditure on what its balance sheet shows as "material consumed". This includes cost of explosives, timber, heavy earth moving machinery and petroleum and oil lubricants. As a downside of the outsourcing strategy, contractual expenses of the company rose 18 per cent to Rs 5,801 crore in 2012-13 as compared to a 6 per cent growth in the previous fiscal. Another factor which acted as a dampener for earnings was interest income.

The company's cash and bank balance increased by a mere 6.9 per cent to Rs 62,236 crore at the end of March 2013. Cash reserves had jumped 27 per cent to Rs 58,202 crore at the end of March 2012. Not surprisingly, the interest income of the company increased from Rs 5,049 crore in 2011-12 to Rs 6,010 crore in 2012-13. This, Rao says, was mainly because interest rates had not gone up last financial year as per expectations.

)