As we drove home at 2 in the morning on a clear night 40 years ago (that August was just as dry in Ahmedabad as this one) after watching a film at the Drive-in, released two days earlier and already declared a box office dud, one visual kept haunting me: an unshaven man in army fatigues carrying a bullet bandoleer, looking at the sky, appearing taller than he was, (because the shot was taken from the ground up) against the backdrop of bare boulders, defying fate itself to come and get him.

I have not seen Sholay since, either on the big or the small screen. So imagine the extraordinary power of that image I so vividly recall. It sums up for me what the movie was all about and its great appeal: an invocation of pure, unadulterated evil that is more spell-binding than any heroism.

Sholay had everything for the audiences, or as the sonorous voice of Ameen Sayani intoned on radio promos, "action emotion se bharpoor", an ever-intriguing revenge saga, heroics of a pair of no-goodniks that would now qualify as bromance, humour that did not stick out, an item number to beat all item numbers (although not called as such then). That made the movie set the box office on fire, through sheer word-of-mouth (no promotions in those ancient days!) But above all, it had Gabbar Singh.

Gabbar is a unique villain, not just in Indian cinema, but globally as well. Supposedly inspired by a real-life eponymous Chambal ravine dacoit, he is nothing like the hundreds of such types we have seen. There is no backstory here, no wrong done to be avenged, no family ties, no sense of bonding with his gang, no outsize libido, nothing. He has no ticks, no weird mannerism, only a hyena laugh that lingers like the Cheshire cat's grin, causing terror rather than amusement. You don't know why he plunders and kills, he just does.

Filmdom is full of legendary bad men: our own Mogambo, Shakal, Dr Deng for instance, and Dracula, Dr Moriarty, Colonel Kurtz, Conquistador Aguirre, and more recently, the Joker, in international cinema. But none of them gets as close to the heart of darkness as Gabbar does, precisely because he has no history, no defining trait save sheer, utterly credible, evil.

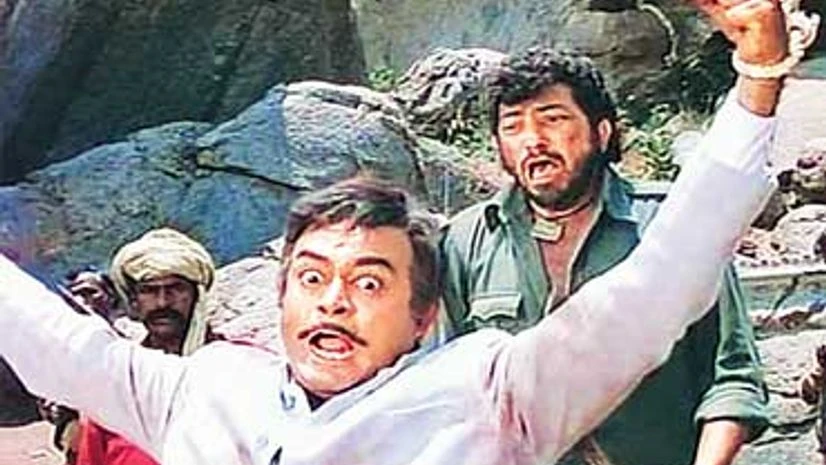

Gabbar on the screen is a triumph in equal parts of brilliant writing by Salim and Javed, definitive histrionics by the debutant Amjad Khan and inspired direction by Ramesh Sippy, in only his third stint at the megaphone. But that towering achievement cannot entirely dwarf other memorable roles and performances: Dharmendra, the buffoonish Lothario, Amitabh Bachchan, his wise-cracking but melancholic significant other, Sanjeev Kumar, the revenge-crazed volcano, and Hema Malini, the garrulous village dumb belle. Asrani's Angrezon ke zamaane ka jailor and Jagdeep's Soorma Bhopali became career-defining performances. Even the many character artistes who made now-you-see-them-now-you-don't screen appearances, shined: Mac Mohan as the lazy Samba, Viju Khote as the simpering Kaalia, Leela Misra as the battle axe of Mausi. And Helen and Jalal Agha in that evergreen anthem, "Mehbooba Mehbooba", are worth a visit to the cinema for themselves.

Treatises have been written on Sholay, trying to explain its social dynamic in caste terms, treating it as a tale of developing India's reaction to feudalism, what is now perceived as homoeroticism of its leading characters, and so on. They all are, to the billions who have enjoyed the film, nitpicking and purely pedantic efforts at finding greater meaning than was ever intended.

One significant take-away for me is how we are fascinated by evil, even as we are born with tribal memories of the good-bad binaries. And it is not even the primordial Mephistophelian trade-off. It is like watching a bird of prey swoop down on its hapless victim and making a quick meal of it. We are revulsed, terrified even, but are transfixed all the same, as Gabbar cackles, teeno bach gaye, and then coolly empties the barrel into three gang members who had failed him.

Sholay borrowed unashamedly from many a masterpiece: unlikely heroes hired to throw back marauders as in Akira Kurosawa's Seven Samurai (originally called The Magnificent Seven, which was the title of its Hollywood incarnation), the brutal violence of Sam Peckinpah's The Wild Bunch and Straw Dogs, stark landscapes inhabited by leathery characters as in Sergio Leone's Once Upon a Time in the West, are among the more frequently mentioned influences (Sholay has been called a chapati Western, a rather inapt and unfortunate coinage, since the film defies genres).

But Sholay was more than all these. It had zest and joie de vivre portrayed by the antics of the two-some heroes, the tongawalli, and sometimes, even the villagers themselves. And although the good guys triumphed in the end, it was the Ultimate Bad Guy that we remember.

Even Gabbar Singh cannot force Shreekant Sambrani get over his addiction to Hindi golden oldies

SHOLAY: Scene unseen

If you thought you knew everything about Sholay, even that Gabbar Singh's father was Hari Singh, try these facts

-

Gabbar Singh, the tallest character of Sholay, had all of nine scenes in the entire film.

-

It took 40 retakes to finally seal the scene with Amjad Khan's legendary line, "Kitne aadmi the?"

-

In one of the last scenes in which Thakur takes on Gabbar, his left hand can be seen peeping out from under his white kurta. Only just, but it is there and what a blooper!

-

Mac Mohan, who played Sambha, travelled 27 times from Mumbai to Bengaluru for the shooting of his role. (The film was shot in Ramanagara about 50 km from Bengaluru).

-

Nowhere in the film do Sanjeev Kumar and Hema Malini appear together in any frame. That would have been rather awkward given that Kumar had just proposed to Malini, and she had turned him down.

-

One lucky actor, Mushtaq Merchant, got two roles in this masterpiece. He first appears as the train driver in the thrilling train scene at the beginning of the film and later as the Parsi man whose motorcycle Jai and Veeru steal.

-

The Bhaag Dhanno, bhaag scene in which Basanti is chased by dacoits was shot over 12 days.

-

The young Sachin Pilgaonkar, who plays A K Hangal's son, is said to have received a refrigerator as remuneration for his acting.

-

While it is widely believed that Sambha speaks only one line in the film, he does have one more dialogue. He is playing cards with the other dacoits when one of them spots Sachin going on a horse to the railway station. Sambha says, "Chal be Junga, chidi ki rani hai", to which his fellow dacoit replies, "Chidi ki rani to theek hai Sambha, who dekh chidi ka ghulam aa raha hai."

- Sholay had trouble with the Censor Board and had to alter the original script at several stages.In the original version, Sachin meets a violent death at the hands of Gabbar. But the Censor Board-approved version, which made it to the screens, shows Gabbar squashing an ant crawling on his arm to depict the murder. It is toned down but no less chilling. Also, in the original ending, Thakur kills Gabbar. But the Censor Board wouldn't condone such vigilantism. So, a new climax was scripted in which the police arrive on the scene, tell Thakur that only the law has the right to punish criminals and then whisk Gabbar away.

)