When M.G. Ramachandran (MGR) was shot by fellow actor M.R. Radha on January 12, 1967, I was probably a few weeks old in my mother’s womb. MGR’s next near-brush with death was 32 years ago, and as an aware 17-year-old, I have distinct memories of it. MGR was admitted to the same Apollo Hospital where his protégé J. Jayalalithaa is now apparently battling for life. The parallels are stronger than mere calendrical coincidence.

MGR was then 68 – so far as birth records are reliable for a man who came from such humble beginnings as him, about the same age as Jayalalithaa is now. He had suffered a kidney failure, and was soon flown to Brooklyn Hospital, New York for treatment. In the wake of Indira Gandhi’s assassination on October 31, 1984, Rajiv Gandhi went in for snap polls a few months ahead of schedule. MGR’s All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) was in alliance with the Congress.

Those were pre-satellite channel days, and the media had great prestige but could easily be thwarted by the government. During the long months of treatment, there was little real news of MGR’s condition but for the periodical press releases that H.V. Hande – now a member of the Bharatiya Janata Party, a physician himself and a minister in his cabinet – issued. The press releases carried little credibility, and in one of his famous wordplays, MGR’s erstwhile friend, sworn political enemy and many-time chief minister of Tamil Nadu, M. Karunanidhi, called it ‘Hande pulugu, anda pulugu, aakasa pulugu’. The line is untranslatable, but the rhyming reference is to ‘blatant lies of universal proportions’.

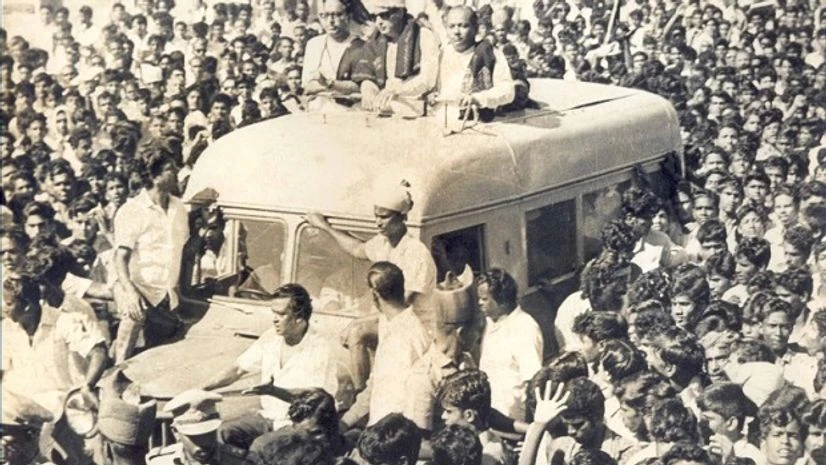

Access to MGR and his wife, Janaki Ramachandran was controlled by a major faction of the party led by Rm. Veerappan, a successful film producer and a minister in the cabinet. In this, the Congress was a willing ally. MGR filed his nominations papers to the Andipatti constituency from his hospital bed in the presence of India’s Ambassador to the United States. Those were pre-RTI days and no one has seen the signed nomination papers to date. Indira’s assassination and MGR’s ill-health formed an unbeatable combination and the coalition swept the polls. Until MGR’s miraculous recovery and return to India some months later, there was no acting chief minister. And when MGR was sworn in, Doordarshan and Films Division, the only media allowed inside Raj Bhavan, decided to mute the cameras!

MGR ruled for three years until his death on Christmas eve, 1987. And these years remain one of the many dark spots in Tamil Nadu’s post-independence governance. Jayalalithaa was side-lined, with little or no access to her mentor, and fought a rear-guard battle with the help of some dissidents. Matters reached their nadir when she was pushed from the gun carriage hearse at MGR’s funeral.

Also Read

In the waters troubled by MGR’s death, the Congress, which had not ruled Tamil Nadu by itself for two decades, began to fish. In a single year, in 1988, Rajiv Gandhi visited the state 17 times, making tall promises. With P.C. Alexander playing the pliant governor, the Congress desperately tried to shore up its fortunes. In the January 1989 elections, it contested on its own under the leadership of G.K. Moopanar. The results not only exposed the Congress’s limitations, but also confirmed Jayalalithaa’s claim to MGR’s mantle. After her resounding victory in the 1991 elections riding the sympathy wave generated by Rajiv Gandhi’s assassination, Jayalalithaa ensured that the AIADMK survived MGR’s death. But, in a bid to emerge as a leader in her own right, she did everything to erase MGR – invoking his name only in crises.

Marx must be turning in his grave every time a lazy political commentator alludes to his famous dictum: ‘Hegel remarks somewhere that all great world-historic facts and personages appear, so to speak, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.’

And yet, it is impossible not to invoke Marx in this context. The parallels and analogies leap off the first page of his Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte.

If MGR made history by being the longest serving chief minister of Tamil Nadu, Jayalalithaa has similar, and other dubious, records to her credit. And her stint in power has not only been longer but also spread over a quarter of a century. If anything, she has widened the AIADMK’s vote bank.

Due to apparent ill-health, accentuated evidently by her incarceration in Parpana Agrahara jail in late 2014, Jayalalithaa has sported a jaded look over the past few years. Her campaign in the recent elections was lacklustre. Public appearances have been stage-managed to give a modicum of normalcy. If heavy make-up disguised possible signs of ill-health, special arrangements were made not to expose her limited mobility. And the sojourns in her Kodanadu estate have, if anything, got only more frequent and longer.

If credible reports were scarce in 1984, paradoxically, in the face of a phenomenal media glut, information now seems to be in even shorter supply. Apollo’s medical bulletins will not convince a primary school student. That even ministers of the central cabinet and the governor of the state have not actually met her only confirms the hold of Jayalalithaa’s friend, Sasikala, and her extended family.

The government remains paralyzed, and none dare even hint that an acting chief minister should hold the baby. At this moment, the BJP at the centre is as soft as the Congress was during MGR’s times, desisting from calling the state government to account. Questions are already being raised if the union government is not failing in its constitutional duties. If the Congress was hoping to gain a foothold in Tamil Nadu in a post-MGR scenario, the BJP is in an analogous position now. But the union government’s volte face in the Supreme Court on October 3, challenging the court’s powers to intervene in the constitution of the Cauvery Management Board, suggests that the BJP is torn between regaining power in Karnataka and gaining a foothold in Tamil Nadu.

The other constant is M. Karunanidhi, and it does speak for the phenomenal staying power of this ever-sharp politician. After two consequent defeats, in 1977 and 1980, he was desperate for a victory in 1984 but could do little to wrest the initiative in the face of twin odds: Indira’s death and MGR’s ill-health. But he had the last laugh at least in relation to MGR, surviving him by three decades, completing two terms in office, and still being in the reckoning for another shot at power. However, it’s been a see-saw battle with Jayalalithaa whom he would have scarce imagined to be a rival when she was prancing on the screen. As he now fights his own son, M.K. Stalin, inside the party, Karunanidhi must fancy that the throne is once more within striking distance.

One wonders what other parallels lie in store.

A.R. Venkatachalapathy is a historian of the Dravidian movement.

By arrangements with The Wire

)