Dhruv Dua can barely hide his excitement as he finds himself closer to his dream of becoming a doctor. A student of Delhi Public School in Indirapuram in the National Capital Region, he is looking forward to a single common entrance test to get into any of the 400-odd medical colleges in the country. "I had filled up forms for six entrance examinations. I am feeling relieved, now that I will have to take just one. And, the common pool is large enough to afford me a chance to get me into one of the decent medical colleges," says an elated Dua.

The excitement of Dua and many others like him, however, is short-lived, as the government has decided to promulgate an ordinance to defer the implementation of the recent ruling of the Supreme Court. The apex court had ordered last month that students would be required to take only one test, the National Eligibility cum Entrance Test (NEET), to get entry into medical colleges in the country.

The apex court had directed the government to hold one such examination on July 24. Separate all-India and state merit lists have to be prepared on the basis of NEET. State governments will have to ensure that seats are filled according to existing reservation provisions and other specified requirements such as domicile status. NEET will only provide a rank to students and institutions will be free to prepare their own merit list based on that.

Depending on the NEET merit score, students will have the option to apply to colleges of their choice and will get selected according to the norms prescribed by states. Logistical issues aside, which states are likely to sort out, the NEET will bring back "the glory of the medical profession", says Dr K K Aggarwal, honorary general secretary of Indian Medical Association.

Why states don't want NEET this year

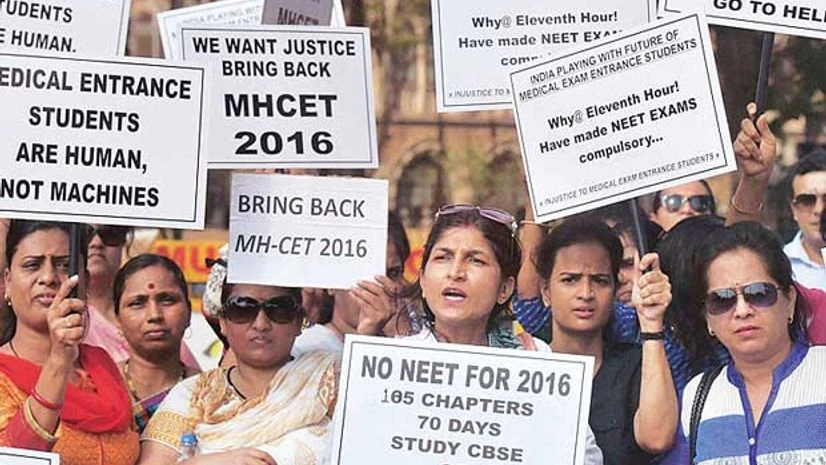

Some states, such as Maharashtra, Gujarat, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana and Tamil Nadu want the test to be deferred. Maharashtra's education minister Vinod Tawde tweeted on May 16 urging the Centre to bring an ordinance "to stop compulsory implementation of NEET this year". Some political parties, too, had raised their objection to the holding of NEET this year. The view coming out of an all-party meeting last week was that the Centre should explore options to defer the implementation of the apex court order by a year.

What are the main objections of the states and political parties? One, they want the tests to be conducted in local languages instead of just in Hindi and English. They argue since most of the students in their respective states are conversant in local languages alone, switching over to English or Hindi will put them in a disadvantageous position.

Their second objection is with regard to the syllabus. They say that since all states offer different curricula to students, asking them all to follow one syllabus will be unfair. One of the main arguments of the states is that there is a difference in curriculum of the Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE) and state boards, and that NEET will favour the former, says Supreme Court lawyer Krishna Sarma.

Sankalp Charitable Trust, one of the petitioners in the case in the apex court, has a different take on these objections. According to a note prepared by the trust, the NEET which was conducted in 2013 had question papers in local languages also but "not a single student of vernacular language could get admission". The reason is that since most textbooks for physics, chemistry and biology - mandatory reading for getting admission in medical colleges - are in English, most serious aspiring students prefer English over local languages. The note says that according to the Medical Council of India (MCI) guidelines, any student is eligible for admission into an MBBS course only if she or he has cleared English at Class 12 level.

"All the objections are really an eyewash. The real reason for continuing with the old system is to continue with the practice of huge capitation fee prevalent in private medical colleges," observes Dr Gulshan Garg, a qualified doctor himself and chairman of Sankalp Charitable Trust. He says he has been overwhelmed with the response his organisation is getting on the issue. "I get calls and e-mails from students. All of them are very happy with the introduction of NEET. But, an impression is given now that it will not be helpful for students. I think it is wrong. NEET should be held without any delay now," he adds.

Experts say that even now, as many as 12 states have dispensed with the system of holding separate entrance tests in their states and take students from the All India Pre-Medical Test conducted by CBSE. These examinations are conducted in English and students from these states are happy to participate. Additionally, almost all of private institutions conduct their entrance tests in English and no one has objected to this practice so far, they add.

| Why some states are opposed to NEET |

|

Maharashtra Chief Minister Devendra Fadnavis was the most relieved man in India as he pumped Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s hand on Friday to thank him for the decision on an ordinance postponing the implementation of the Supreme Court order on the National Eligibility-cum-Entrance Test (NEET). Private medical colleges, owned by not-for-profit societies and individuals, account for the bulk of Maharashtra’s Rs 12,000-14,000 crore private medical college economy. Admission to these colleges is not primarily on merit. Those who can afford to pay, manage to get in. Although their course and syllabus (in most cases) is certified by the Medical Council of India, these colleges churn out doctors in large numbers for whom thresholds of education are lower than doctors who get into, say, an institute like the All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Delhi. This economy is fuelled largely by cash. Look at the trend of new medical colleges in the past 15 years. Out of the 151 that have been established by the private trusts, a majority (99) have come up in the affluent states of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Gujarat and Maharashtra. Little wonder, then, that these states are the ones who have been saying most aggressively that the Supreme Court order should be reviewed. Here’s how it works: Money is spent to set up a medical college. Fees are paid and these can be five to 10 times the fees in government medical colleges. Setting up medical colleges is not cheap – permission and clearance alone can cost a lot of money. Once the students start coming in, the licence and permission costs are paid off. This could be in the form of sponsoring candidates in elections; or other means. A top political source in Maharashtra said if a common entrance test to get into medical colleges is made mandatory, it will be impossible to manipulate entry into these colleges. |

Half of MBBS seats in private medical colleges

The total number of seats for MBBS available in the country till last year was 49,900. According to reliable estimates, 25,330 of them are available in government medical colleges and 24,660 are in private medical colleges. Experts say that there are at least 100 different entrance tests conducted every year for prospective students to get admission in these medical colleges. And, entrance examination fee ranges from Rs 1,200 to Rs 6,000. This means, an expenditure of nearly Rs 25,000 if a student chooses to appear for six or seven entrance tests at different places. And, it does not include the cost involved in travelling to take entrance examinations in various cities.

To take care of these hassles faced by students, the idea of a common all-India entrance test was first mooted in 2010. And, the MCI amendment had recommended a common examination for admission to MBBS course every year. The idea was to model NEET on the lines of globally accepted examination systems such as SAT, GRE or TOEFL.

The first NEET was conducted in 2012, but 90 medical colleges went ahead with separate entrance tests on their own. The Supreme Court passed an interim order in May 2012 making NEET voluntary permitting medical colleges to take admissions based on their own examinations. The final judgment delivered in 2013 quashed the MCI notification for holding NEET. The Centre filed a review petition in August 2013. The latest decision is in response to the review petition.

Incidentally, a recent report of the Parliamentary standing committee on health and family welfare strongly advocates a transparent process of admission on the lines of NEET. Since the process is missing at the moment, "private medical colleges/ universities have developed their own screening and admission procedures which are primarily monetary based."

Menace of capitation fee

The committee further observes that "it is public knowledge that the majority of seats in private medical colleges are allotted for a capitation fee going up to Rs 50 lakh and even more in some colleges despite the fact that it is illegal. This capitation fee is exclusive of the yearly tuition fee and other expenses. The Committee observes that the issue is not just about capitation fee. This has serious implications for our whole system of medical education and healthcare."

The existing system keeps the meritorious but underprivileged students out, it says, and if "a unitary Common Entrance Exam is introduced, the capitation fee will be tackled in a huge way; there will be transparency in the system; students will not be burdened with multiple tests; and quality will get a big push."

Geographical concentration of medical seats

Experts say that medical education in the country not only suffers from the bane of huge capitation fees, it also suffers from concentration of medical colleges in a few states. According to reliable estimates, nearly 65 per cent medical colleges are concentrated in the southern and western states of the country. This has resulted in great variation in doctor-population ratio across the states. States in the north, northeast, and central India have a severe shortage of doctors because of the fewer number of medical colleges in these states. According to the standing committee report, "six states with 31 per cent of India's population account for 58 per cent of the MBBS seats, while eight states which comprise 46 per cent of India's population have 21 per cent of the MBBS seats".

Other than having a NEET that will likely take care of the growing menace of capitation fee, the government should ensure more even-spread of medical institutes to improve the doctor-people ratio and increase the access to healthcare in the country, say experts. With NEET likely in place following the Supreme Court decision, will the other measures follow?

)