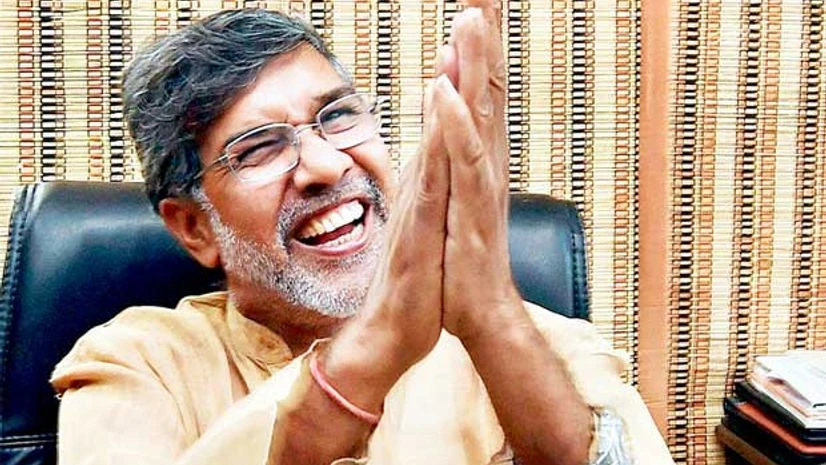

When an Indian citizen had last won a Nobel Prize - Amartya Sen for Economics in 1998 - the prize was much celebrated in the country, and the winner was awarded a Bharat Ratna the next year. But that was 16 years ago. Today, even as another Indian, Kailash Satyarthi, is set to jointly receive the Nobel Peace Prize for 2014 with Pakistan's Malala Yousafzai, its acknowledgment looks unlikely to match the rapturous festivities in the wake of Sen's honour.

There has been "a lack of real enthusiasm" in lauding the Nobel Prize to Satyarthi in India and to Yousafzai in Pakistan, says Ashis Nandy, one of India's leading social scientist. "I don't want to get into the strengths or flaws of the man (Satyarthi). But child labour is not a very appealing subject. The Indian middle class agrees that child labour is not a happy thing but would want to say little on it publicly," Nandy says of the relatively muted response that Satyarthi's Nobel has evoked among India's industry, intellectuals, politicians, activists and the media.

Ranjana Kumari, director of New Delhi-based Centre for Social Research, somewhat agrees with Nandy. Kumari, who works among rape and dowry victims, says activists like Satyarthi and herself are frequently accused of showing India in a bad light. "Satyarthi has worked for child labourers, the most vulnerable and voiceless section. Our effort is to tell the truth about our society, fight and change it. We should appreciate the honour; after all, he is an Indian. We should not read motives in it (the Nobel Prize)," Kumari says, but adds she is against any 'exhibition' of India's social evils before the West.

More From This Section

The Confederation of Indian Industry (CII), however, issued a statement after Business Standard inquired on Saturday. Ficci said it could give a comment, if we so wished. In its statement, CII said it was delighted at a Nobel for Satyarthi. "CII and CII Foundation have always opposed child labour and are encouraged and guided by the spirit of the work done by Mr Satyarthi," it said.

There are many among the larger activist community who view Satyarthi's achievement with some suspicion. Few in mainstream journalism have heard about the man or his work. Vivek Bhardwaj, a journalist, confesses in his blog on firstpost.com that the ignorance among journalists is "because we did not identify with his (Satyarthi's) cause". "Many things in India do not shock us: Dirty roads, stinking public toilets, men urinating in public places, a six-year-old taking orders at a road-side tea stall or an eight-year-old mopping floors. These are part of Indian 'culture'," he says.

Nandy also points to the blogosphere and social media being relatively silent on the honour to Satyarthi. The social scientist says Satyarthi would have been branded anti-national and anti-development and been much in news if he had won the award for protesting against nuclear energy or for environment protection. “Look at how quiet the Non-resident Indians are. They are usually very active on blogs and social media about Indians bringing glory to Mother India. But Satyarthi’s work is about the inglorious aspects of Mother India. In this era of epidemic form of nationalism, Satyarthi’s is not a glorious achievement,” Nandy says.

Both Kumari and Nandy are, however, happy that Satyarthi’s award has vindicated the much maligned NGO (non-government organisation) sector. Meenakshi Ganguly of Human Rights Watch says human rights movements are viewed with suspicion by the state and the recognition to Yousafzai and Satyarthi could be seen as giving encouragement to such movements. “But I feel Satyarthi was not as well known as Malala, even in India. And, that could probably explain the lack of enthusiasm. We, however, should look at the broader picture of this being a representative award for all those working in the field of child rights,” she says.

R Vidyasagar, child protection specialist with Unicef, says Satyarthi’s award should lauded, irrespective of what opinion one might have about the individual and his contribution to the cause. “This award brings into focus the cause of children and is strategically very good, as the issue has not been a priority for the state or the media.”

Is Satyarthi unsung because many among bonded and child labourers are from Dalit communities? Professor Badrinarayan of Allahabad’s G B Pant Social Science Institute, an expert on Dalit politics, disagrees. He attributes the lack of interest on the poor view that people generally have of NGO work. “I do not think this is much of a caste issue. Child labourers come from all castes. The problem is that few of us let an opportunity go where we can exploit child labour, whether in mopping the floor or running errands. The problem is that NGOs, at times with good reason, are viewed with suspicion. Also, Satyarthi does not have such a stature in India yet that somebody like Amartya Sen had at the time of receiving the award,” he says.

Professor K Gopal Iyer, a retired professor of sociology and an expert on child labour, says the state in India has been apathetic to the issue of child labour. Neither the Centre nor state governments have accorded proper recognition to the work. “In that context, the Nobel should be welcomed. But this is a collective endeavour and not an individual one. A lot of people have contributed to highlight the issue. It is this group that should have been awarded, not merely an individual,” Iyer says.

)